Damaged left thrust reverser of the accident jet.

Two weeks after the March 2019 crash involving an IAI Westwind in Yukon, Oklahoma, two people who were familiar with jet told the NTSB investigator-in-charge that the aircraft had had an inadvertent reverser deployment four-to-five weeks before the accident.

The earlier incident took place when the jet exited the runway after landing, and both pilots involved in the crash knew about it. In fact, the accident copilot was flying the jet when it happened. The event had been reported to an FAA inspector at the Oklahoma Flight Standards District Office.

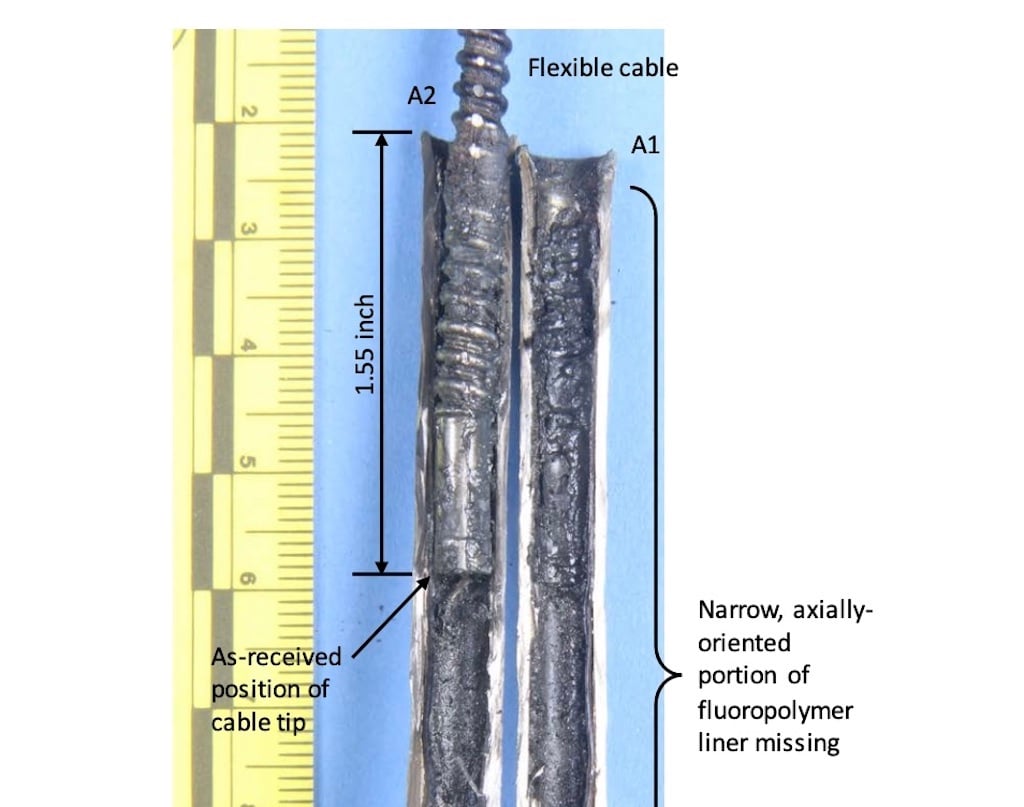

The lead investigator of the accident in Yukon, Oklahoma, coordinated with the NTSB’s labs to have components of the throttles examined. A specialist arranged to have the components scanned by x-ray radiograph and computed tomography. The scans conducted in a Chicago lab showed multiple irregularities. Of special note, there was missing, displaced, or distorted liner material in the thrust reverser Teleflex cable. There was also old black grease along the inside sheath of the thrust reverser control cable.

The throttle components were shipped back to the NTSB’s materials lab. There, an engineer found that the left micro stow switch in the throttle did not work as designed, and both the left and right stow switches showed arc wear due to aging.

There were also other thrust reverser components that were not airworthy and that would have affected control of the system. The electrical wiring of the left thrust reverser did not conform to the manufacturer’s electrical drawings. There were missing connections on the terminal board, the terminal board cover was missing, and wires were not of the proper length and were not properly secured. The CT scan of the left actuator “OUT OF STOW” switch showed an internal rivet was broken.

In addition, the left thrust reverser retarder system was jammed in a midway position, and it was only freed when the Teleflex cable was removed. This discovery very likely explained why the retarder in the 2014 accident in Huntsville, Alabama, didn’t work right.

Years Of Maintenance Neglect

The ancient black grease, the damaged Teleflex cable, the worn stow switches and the jammed retarder all pointed to years of neglect. Jumbled and broken wiring in the reverser controls pointed to inept repairs.

Another example of shoddy maintenance was the poor condition of the required cockpit voice recorder, which had also been neglected. The last flight when a voice recording was made was in 2007.

That the jet continued to serve for so many years despite poor maintenance is, in a way, a tribute to their sturdiness. As long as pilots handled the throttles gently, the thrust reversers remained closed in flight.

The NTSB found the probable cause of the accident at Sundance Airport to be the jet’s “unairworthy thrust reverser (T/R) system due to inadequate maintenance that resulted in an asymmetric T/R deployment during an approach to the airport and the subsequent loss of airplane control.”

It is likely the accident jet in Huntsville, Alabama, was afflicted with the same kind of hidden deterioration as the jet in Oklahoma.

The NTSB did not question IAI’s testing and certification assumptions regarding the pilot’s ability to control the Westwind with a reverser deployed. The conditions the two accident jets experienced were probably outside those that pilots could realistically be expected to handle.

The aircraft were both very close to the ground, and both were slow. The onset was sudden and unexpected. The thrust retarders did not function properly. Pitch up slowed the jets, particularly the jet at Sundance Airport aircraft. Two sets of experienced pilots could not recover from reverser deployments that test pilots were able to manage. It may be that the flight tests weren’t sufficiently realistic.

Manufacturer IAI’s flight tests, which were conducted in 1976, justified the removal of an important safety feature. The Westwind had been designed with a nose gear contact switch that disarmed the thrust reversers in flight. In 1977, IAI issued a service letter authorizing the removal of the switch at the owner’s discretion. Neither accident jet had the nose gear switch. If they had, it would have prevented the accidents.

Another question must be asked. The jet that crashed at Sundance Airport was 41 years old. Both pilots knew about the recent previous inadvertent deployment and were concerned enough to notify an FAA inspector. Yet, apparently, no steps were taken to troubleshoot the problem and fix it before the accident. Why? I suspect many pilots know that old aircraft develop anomalies, and they accept the added risk. However, a thrust reverser is one system where risks should not be ignored.

Considering the age of the Westwind fleet and the likelihood of inconsistent maintenance on the thrust reverser system, an FAA airworthiness directive requiring reinstallation of the nose gear contact switch is probably appropriate. It could be a lifesaver.

Westwind Thrust Reversers Deploy Unexpectedly, Part 1: https://aviationweek.com/business-aviation/safety-ops-regulation/westwi…