This is the first of a two-part series of a loss-of-control situation involving a Cessna Citation CJ2

Shortly after taking off from Clark Regional Airport (KJVY) in Jeffersonville, Indiana, on Nov. 30, 2018, a Cessna Citation CJ2 rolled sharply left and crashed just 8.5 mi. northwest of the airport.

The task of trying to understand what caused the roll and why the pilot failed to recover from it took the National Transportation Safety Board almost three years. In the end, they were able to provide only partial answers.

The airplane was retrofitted with winglets and wing extensions that contained active aerodynamic surfaces, and that system became the main focus of the accident investigation. The airplane struck the ground with great force, leaving only fragmentary evidence.

The NTSB’s conclusion was based largely on a close examination of the parts of the winglet system that were recovered. The winglet manufacturer saw things differently. In two lengthy submissions, they strongly disagreed with the Safety Board’s conclusion.

The accident airplane, N525EG, took off from Clark Airport at 10:24 Central Standard Time. On board were the pilot and two passengers--the airplane’s owner and a vice president of his architectural firm. The IFR flight was destined for Chicago’s Midway Airport (KMDW) and was operating under FAR Part 91.

The flight’s initial ATC clearance was to fly direct to the STREP intersection and maintain 3,000 ft. MSL. The pilot announced his departure from Runway 36 on the common traffic advisory system (CTAF) before taking off.

He quickly entered an overcast at about 800 ft. AGL. Flying as a single pilot, he verbalized his actions, and his remarks were recorded by the airplane’s cockpit voice recorder (CVR). He set maximum cruise thrust, turned on engine synchronization, turned on the yaw dampers and set up direct to STREP in the navigation system. Passing 1,400 ft. MSL, he turned left on to a course of 330 deg., engaged the autopilot and continued his climb.

At 10:25:40, the pilot checked in with ATC. “Louisville departure, Citation five two five echo golf direct STREP leveling at three thousand.”

Louisville responded, “Citation five two five echo golf, Louisville departure, climb and maintain one zero thousand and ident. The Louisville altimeter is two niner niner niner.” The pilot acknowledged, pressed the ident button, and continued his climb.

While the pilot was running the after-takeoff checklist, Louisville said “Citation five echo golf, contact Indy center one two four point seven seven.” The pilot read back the frequency change and continued verbalizing his checklist.

“Uhhh let's seeee. Pressurization pressurizing, anti-ice deice systems are not required at this time.”

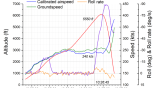

Ten seconds later, at 10:26:45, the airplane began to roll left, and the CVR recorded the sound of a click, followed by an electronic voice announcing “autopilot.” The pilot immediately cried out “whooooaaaaah,” and an electronic voice began to repeat “bank angle, bank angle.”

At 10:26:57, the airplane reached its highest point in the flight, 6,100 ft. MSL. It then began a steep descent, exceeding 11,000 fpm. The airplane continued to roll, and at 10:27:05, it reached almost 90 deg. of left bank.

At 10:27:11, an overspeed warning began and continued to the end of the recording. The pilot responded with shouted expletives.

At 10:27:18, the bank had decreased to about 53 deg., but the airspeed had increased to about 380 kt.

At 10:27:19, the pilot shouted on the radio “Mayday mayday mayday, Citation five two five echo golf is in an emergency descent, unable to gain control of the aircraft.” Four seconds later, an electronic voice announced “terrain, terrain,” and 4 sec. after that, the sound of impact was recorded.

There were no survivors.

The Investigation

Investigators were able to account for all major components of the airplane at the accident site. The debris field was about 400 yd. in length and there had been a post-impact fire. A layout reconstruction of the primary flight controls at the accident site showed all flight control cables were broken in multiple locations.

There was no evidence of pre-impact failures of the flight controls.

The engines’ full authority digital engine control (FADEC) units were found and sent to the manufacturer for examination. No anomalies were recorded. Portions of the enhanced ground proximity warning system (EGPWS) and the Cessna aircraft recording system (AReS) were found. However, the EGPWS internal components were not found, and the memory chip from the AReS was missing.

A control unit for the winglet system in the wing root fairing, the Atlas control unit (ACU), was found. It was crushed and components were missing from the main circuit card, precluding testing. A cockpit warning light for the winglet system (ATLAS INOP) and its supporting unit were not found. However, portions of the winglets themselves and their controls were located in the wreckage.

The portion of the winglet system that moves is called the Tamarack active camber surface (TACS), and each winglet’s associated control box is called the TACS control unit (TCU). Parts of both TACS were found and both TCUs were also recovered.

The wreckage was moved to a storage facility in Springfield, Tennessee. On Oct. 1, 2019, 10 months after the accident, an NTSB systems group was formed. In addition to the NTSB group chairman, the group included experts from the FAA, Textron Aviation, Tamarack Aerospace Group and Lee Air.

First, the TACS and TCUs were taken to Chicago for a computed tomography scan. Next, the components were taken to Lee Air, in Wichita, for a teardown. Then, in November 2019, the left TCU printed circuit board (PCB) was examined in the NTSB’s Washington materials lab using a scanning electron microscope. Additional scans and inspections went on through May 2020.

The Citation 525A, also known as the CJ2, was built in 2009 and had 3,306.5 total flight hours at the time of the accident. The aileron trim bearings were replaced in March 2018, and the Tamarack Atlas active winglets were installed two months later, on May 27, 2018. Both Atlas TCUs were serviced by Lee Air in July 2018 in accordance with a Service Bulletin, and both winglet tip caps were repaired in November 2018. At the time of accident, the airplane had flown 257 hr. and made 188 landings since the Atlas system was installed.

Tamarack’s first supplemental type certificate (STC) for Atlas was issued by the European Union Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) in 2015, and by the FAA in 2016. Tamarack says on its website that the Tamarack active winglets are “a three-part system consisting of a wing extension, winglets and our Atlas load alleviation technology.” The winglets are designed to improve efficiency and climb performance as well as turbulence canceling. The load alleviation system “turns off” the winglet in specific conditions, eliminating additional loads. The system is automatic and autonomous.

The CJ2’s primary flight controls are operated by cables, and the autopilot’s servos are connected to those flight controls by cables. Excessive servo torque or current will cause the autopilot to disengage. According to the aircraft operating manual, when the pilot disengages the autopilot, there is a single tone or verbal alert. When an abnormal condition causes the autopilot to disengage, there may be repeated alerts that can be canceled by the red disconnect button on either yoke.

An autopilot abnormal disconnect can be caused by failures of the yaw damper, the autopilot itself, the attitude heading reference system (AHRS), loss of main DC power, a stick-shaker stall warning or excessive attitudes, including exceeding 45 deg. of bank.

See Part 2 for the remainder of the story.