The Learjet 60 is shown stopped against a perimeter fence at Chicago Executive Airport.

What are the common factors that lead to pilots landing on paved surfaces other than the one they intended—wrong runways and taxiways? There are three recent examples, and all involved professional crews in commercial operations.

Each event had some common factors and some unique factors. All the events took place at night at airports where there was no tower, or the tower was not in operation. All involved crews that weren’t working well as a team. Two were Part 135 Learjets, and one was a Part 121 DHC8-400.

Let’s start by looking at a Learjet 60 accident at Chicago Executive Airport (PWK) on Oct. 21, 2020. The airplane, registration N1128M, was being operated on a Part 135 nonscheduled charter flight and had two pilots and six passengers aboard. The flight left Cleveland’s Cuyahoga County Airport (CGF) at 21:58 central daylight time (Chicago time) after some passenger-related delays. It arrived in the vicinity of Chicago about an hour later.

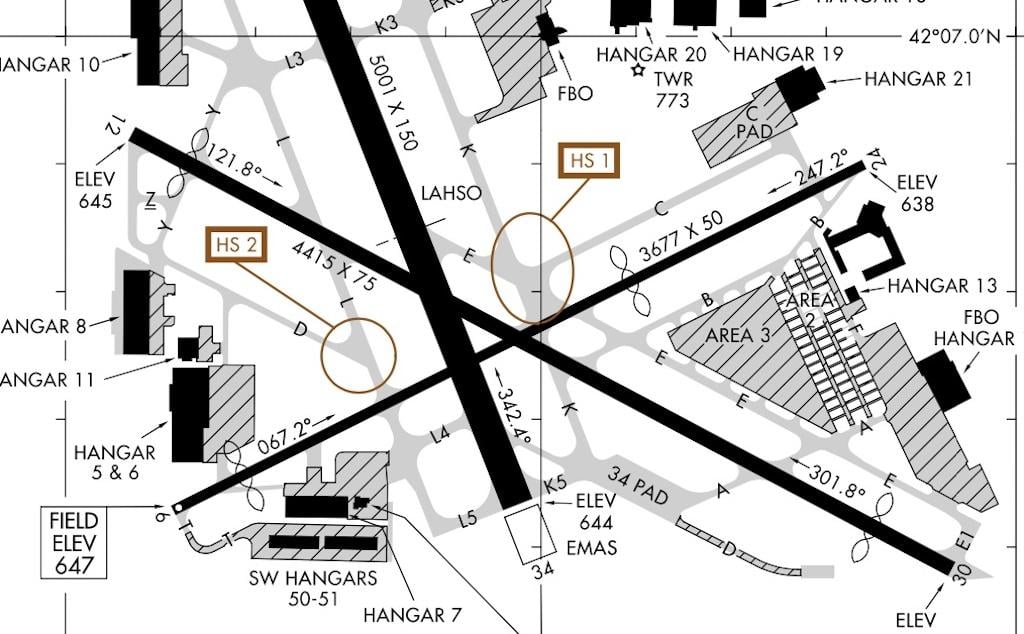

Chicago Executive Airport is located just 8 nm north of O’Hare International Airport and its Class D airspace occupies a niche carved out of O’Hare’s’ Class B airspace. There is a control tower, but on the night of the accident it closed at 22:00. Runway 34 was 5,001 ft. long. The other two runways were far too short for the Learjet to land on.

The captain, who was a check airman at his charter company, calculated the jet’s expected landing performance on Runway 34 before departing Cleveland. He assumed the runway would be wet, and found the required (factored) distance would be 4,790 ft. He did not plan to land on Runway 16, which had an ILS approach, because at the time of departure the latest METAR at PWK reported that winds were 030 degrees at 6 kt., a modest tailwind.

By the time the flight arrived, the weather surface observation had changed. At 22:52 the wind was 080 degrees at 7 kt., visibility was 10 mi., and there was an overcast sky at 4,500 ft. above the ground. There had been rain, but it ended at 22:50.

Visual Approach To Runway 34

The copilot was the pilot flying during the first part of the flight. The captain took over flying duties for the approach and landing. During the descent into Chicago, the captain said he planned to fly the ILS to Runway 16 and circle to land on Runway 34, but he amended that plan and said he would fly a visual approach to Runway 34.

At 22:40 Chicago Approach cleared the flight for a visual approach. The captain reminded the copilot that he should read back the runway, and he said, “no you don’t, a visual’s a visual.”

At 22:45 the controller said “november two eight mike I understand there’s there’s uh some moderate precip ahead about ten miles I'd rather you have go right around that weather stay away from O’Hare.” Four minutes later the controller cleared the flight direct to the airport.

The copilot entered a PVOR (precision VOR) for Runway 34 into the flight management system (FMS). A PVOR provides an electronic display of the intended runway extended centerline, allowing the pilot to be oriented to the intended runway. The captain’s display showed the course to Runway 34, but the copilot’s display did not.

At 22:52 the captain said, “seven miles still” and the copilot replied “ah I got it in sight. It’s in the cluster of all those white lights up there. I got the runway that we're in line with…”

A minute later the crew made a commitment.

Copilot: “you got uh... three four in sight?” Captain: I don't have three four, but I got the other one.” Copilot: “oh you got the uh flashing lights?” Captain: “okay I got it in sight yeah. flaps twenty please.”

The runway they saw was Runway 30, which had an available landing distance of 3,983 ft.

The crew extended the gear and flaps and began running the landing checklist. They continued the approach without any further discussion about the runway. After landing, they were unable to stop the jet and the captain purposely steered the aircraft to the left. They overran the runway and stopped by the airport perimeter fence. The right wing was damaged, but no one aboard was injured. Neither pilot was aware they landed on the wrong runway until after landing.

In an interview with NTSB investigators, the copilot said he clicked the microphone 7 times to bring up all the airport lighting, and all lights responded, including those on Runway 34. He said he felt rushed to complete the landing checklist and he never thought to confirm the heading. He didn’t remember seeing the runway numbers on the runway.

The captain confirmed that “heading” was an item on the landing checklist. The copilot had indeed said “heading” as part of reading that checklist, but he rushed through that checklist only a minute before landing, and the captain never responded.

There was a big difference in age and experience between the captain and the copilot, and that contributed to their poor communication. The captain was 70, had 20,863 total flight hours and 1,389 hr. on type. He spent 20 years with American Airlines, then flew for a foreign airline before entering the Part 135 world. The copilot was 27, had 3,530 hr. total flight hours and 470 hr. on type. The cockpit voice recorder captured multiple disagreements between them during the flight.

The captain said full briefings were discouraged in the Part 135 world. One Part 142 school program manager had told him about briefings, “if it was more than three sentences, it was too lengthy.”

The captain had not flown into PWK in a long time and the copilot had never been there. Their discussion about the approach into that airport was disjointed and minimal, and did not include information about lighting, runway markings, setup of the FMS, go around or planned taxi after landing.

The NTSB’s probable cause was “the flight crew’s misidentification of the landing runway, which resulted in a runway overrun and the airplane’s impact with the airport perimeter fence.”

The safety board might have added, “very poor crew communication” and “inadequate performance of pilot monitoring duties.”

We will look at a Learjet 55 wrong runway landing in an upcoming article.