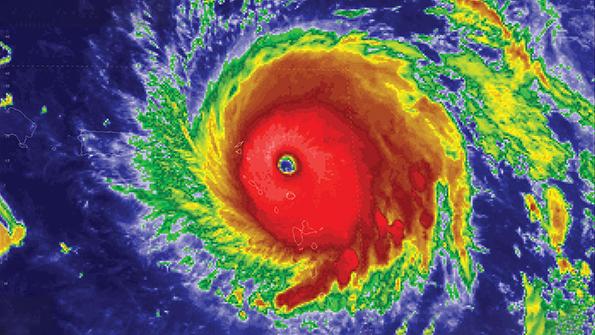

Credit: National Hurricane Center

“What part of ‘No’ don’t you understand?” Lorrie Morgan’s hit country single of long ago might well have served as mood music this past December during jury deliberations at the Boone County (Kentucky) Courthouse. Under consideration were the particulars of a job termination that occurred four years...

Subscription Required

This content requires a subscription to one of the Aviation Week Intelligence Network (AWIN) bundles.

Schedule a demo today to find out how you can access this content and similar content related to your area of the global aviation industry.

Already an AWIN subscriber? Login

Did you know? Aviation Week has won top honors multiple times in the Jesse H. Neal National Business Journalism Awards, the business-to-business media equivalent of the Pulitzer Prizes.