In Part 2, we discussed the NTSB’s initial investigation into the accident at Presque Isle, Maine.

An Operational Factors/Human Factors group investigated the pilots and CommutAir’s management, policies and procedures.

The 40-year-old captain had a somewhat checkered career. She had accumulated 5,655 total hours and 1,044 hr. on the EMB-145 but had moved around between airlines in the midst of proficiency issues.

She left her first job at Republic Airlines after failing to pass her ATP check, then joined CommutAir as an FO. She had a stint at Virgin America, where she completed a type rating in the Airbus A320 but returned to CommutAir, again as an FO.

The company delayed her upgrade to captain, and when she attempted to upgrade on the EMB-145 she was disapproved for steep turns and engine failure takeoff. She completed her upgrade in October 2017 but remained on an “increased scrutiny” status with the company.

Check airmen were very complimentary about her performances on a LOFT (line-oriented flight training) and proficiency check in 2018. She had no accidents or incidents before the accident in KPQI.

The 51-year-old FO had accumulated 4,909 total hours of flight time and 470 hr. in the EMB-145. His experience was mostly in FAR Part 91 operations before he was hired at CommutAir in May 2018. He completed his EMB-145 type rating in July of that year with no noted difficulties. His most recent recurrent training was two months before the accident.

The NTSB found two physiological concerns for him: a recent bout of flu just before the accident flight, and not using his CPAP (continuous positive airway pressure) machine. The night before the accident flight he had less than normal sleep, and probably was in a 2- to 3-hr. sleep deficit.

CommutAir had an FAA-accepted safety management system program in place, and it included FOQA and several safety reporting systems.

One safety manager said the company received over 700 ASAP reports a year but had received no pilot reports about the KPQI localizer. Six CommutAir pilots had noted the localizer discrepancy at KPQI in the five days before the accident, but none had reported it to the company. The accident FO was one of these pilots!

Conclusions and Comments

In thinking about all the ways this accident could have been avoided, the first thing that comes to mind is the captain calling the runway in sight when she did not have a view of the landing surface at all.

The second thing is the FO should have gone no lower than 100 ft. because he never saw a runway either. Both broke the fundamental rules listed in 14 CFR Part 121.651 about when you can descend below the decision altitude to touchdown.

The NTSB explained the pilots’ actions as the result of confirmation bias.

They explain that “Confirmation bias is an unconscious cognitive bias that involves a tendency to seek information to support a belief instead of information that is contrary to that belief.”

The perfectly crossed ILS steering bars were certainly a strong reason to believe the flight was in the right place.

This situation could have fooled many pilots.

The NTSB came out with a safety alert in 2011 about avoiding “rote callouts.” Several accidents had taken place after pilots had called out indications that hadn’t happened. “Thrust reverse deployed,” “spoilers deployed,” “lift dump,” “flaps.”

These were part of repetitious, highly proceduralized routines done in a short time span. The pilots were so used to making the standard callouts, they missed actually verifying the indication they expected to see.

Judging by the cockpit voice recorder transcript, the captain was a wizard at standardized procedure. It seems to me she made the “runway in sight” callout more from rote memory than real visual contact.

The NTSB also faulted the FO’s fatigue state and the failure of pilots to report the localizer anomaly.

The NTSB’s probable cause was “The flight crew’s decision, due to confirmation bias, to continue the descent below the decision altitude when the runway had not been positively identified.

Contributing to the accident were (1) the first officer’s fatigue, which exacerbated his confirmation bias, and (2) the failure of CommutAir pilots who had observed the localizer misalignment to report it to the company and air traffic before the accident.”

I question the wisdom of having the FO fly the first leg of a trip when the two pilots haven’t flown together before. It’s an important time to establish roles, captain’s authority and personal preferences. Some companies also require the captain to fly approaches to low minimums.

One tip-off for this captain’s decision was her remark about “going up and down” when transitioning to visual conditions. She wouldn’t believe that if she were herself proficient in low-visibility landings.

There’s one more factor to consider here. A whole slew of people could have prevented this accident if they had been more safety conscious and more proactive.

The ATC manager could have closed off the ILS until someone had time to check its signal.

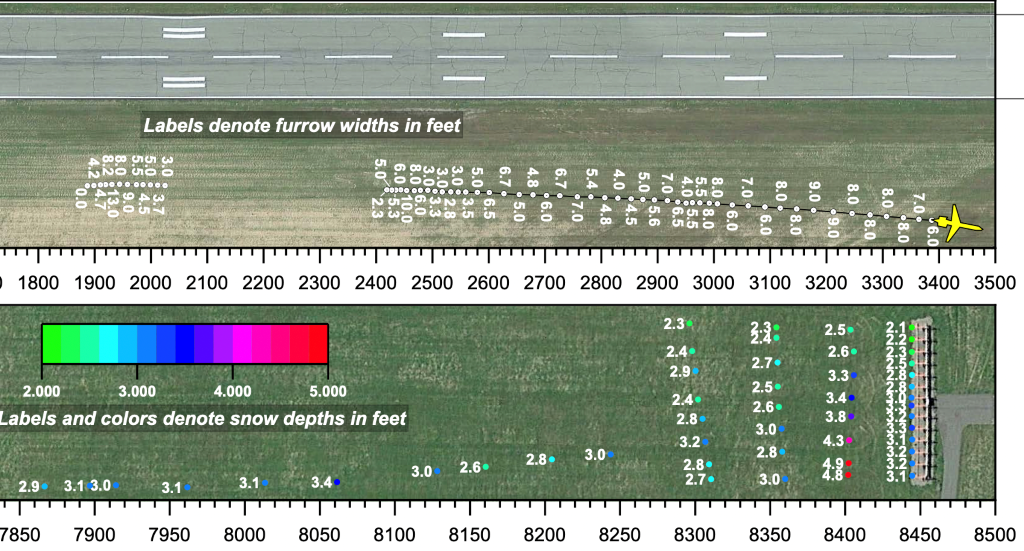

The KPQI operations staff could have asked for an FAA ILS check when the snow got so deep.

The airline’s certificate management office (CMO) could have been more alert to winter hazards at KPQI.

The pilots who noticed the problem could have reported it immediately.

And last of all, the accident FO could have put two and two together and been ready for the localizer signal to be off-center, having already noticed it on an earlier flight.

Aviation must have a culture of continuous vigilance, not just by pilots, but by everybody. Safety is not someone else’s job.