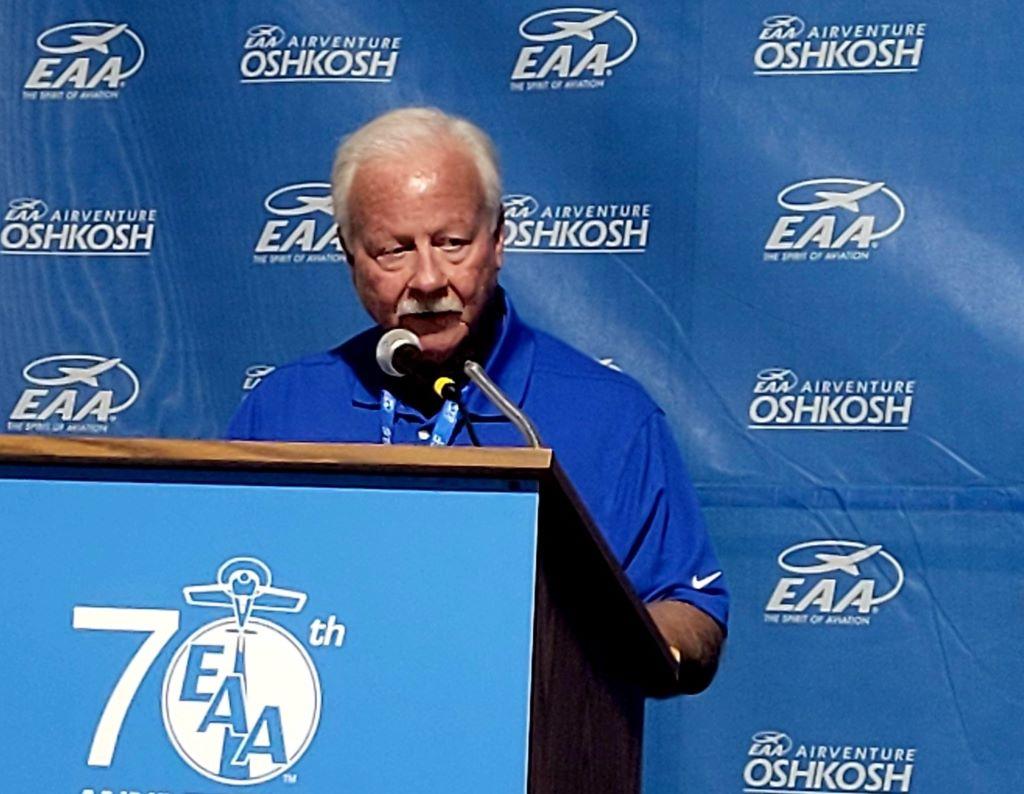

Fast Five With EAA's Jack Pelton

Jack Pelton is chairman and CEO of the Experimental Aircraft Association (EAA). Pelton was elected Chairman of the Board in 2012, the first chairman in EAA’s history to be elected from outside the founding Poberezny family. He was named EAA’s CEO in 2015. Pelton is the retired chairman, president and CEO of Cessna Aircraft Co., now Textron Aviation. Pelton, whose parents were both pilots, holds airline transport and commercial pilot certificates and has earned instrument, multi-engine and seaplane ratings. BCA caught up with him ahead of EAA AirVenture 2023.

The Environmental Protection Agency has mandated finding a replacement for leaded aviation fuel by 2030. You mentioned it as the top issue for EAA and for general aviation as a whole. What is the status?

We’ve been using lead in aviation fuel since the '30s or '40s. It’s a very small amount in the fuel but with the enhanced attention on the environment, it made it to the top of the list of the EPA-issued endangerment finding. We need to get rid of the lead. It’s been very hard to do, too, because lead is a unique chemical you put into fuel that has a lot of really good properties and that causes the octane rating of fuel, which is the burn rate of it to be higher than what you can create just with conventional fuels like auto fuels. We’ve got four fuels that we’re working with. Two of them have been approved to put in airplanes but no one is manufacturing and distributing those fuels widely. So, we’re looking at two other fuels that are being produced by petroleum companies and trying to come up with what’s are the petroleum companies going to pick as their one fuel that they will license, market and distribute to all the existing airports with the goal being that they’re compatible with the old fuel, so you can use either or as you make the transition. So, if I had access to the new fuel today, I could use it. If I go to an airport that doesn’t have it, I could still put 100 low-lead in my airplane and they would still mix together and work well.

Doesn't one of the biggest pain points with the issue involve how to take care of high-performance aircraft?

A. Yes. It’s the high-performance piston aircraft that are the ones that require the 100-octane fuel. There’s some 94-octane fuel with no lead in it today you can buy from Swift, it’s great for about 65-75% of aircraft engines, but the Cirrus and some of the other ones can’t use it. They need 100 octane. That’s the big one [finding a replacement]. We’ve got to find a solution. Most people are going to be impacted.

With all the new technology and Advanced Air Mobility (AAM) projects in the works, what do you think AirVenture will look like in 10 or 15 years?

I think the difference between this year and 10 years from now will be the expansion of having the AAM folks as one of EAA’s [dedicated areas.] We have vintage; we have warbirds; we have the aerobatic aircraft; we have homebuilt areas. You’ll see in 10 years, there will be an area dedicated to AAM type of aircraft.

How do you feel about the upcoming pilot pipeline. Are there enough young people to back fill openings in the horizon?

Everything I look at and look into says that problem is real, and it’s going to be around for a long time—between retirements, and we’re not filling [the pipeline] fast enough. Compared to when my kids were growing up, where it was tough to justify the expense of pursuing that career because the career didn’t pay nearly what it costs to get qualified and get your ratings and all that. It’s a really healthy industry now, where the pay scale for pilots is really good. We need as many mechanics as we need pilots, so we’re focusing on the young kids as far as how to get them interested and attracted.

How is EAA reaching out to young people in hopes of helping or filling that pipeline?

Our strength, of course, has been our Young Eagles program. That’s been our bread and butter for getting young people interested in aviation by giving them their first flight at no charge. Then we have built and launched in the last 12 months a program called Aero Educate. After the young person has taken the flight, they have the ability to log onto an EAA portal that has educational activities for the young person, schoolteachers and their parents with career track kinds of lessons and projects to work on to keep them engaged. Because once they leave the airport, they’re kind of on their own, and if they don’t have any mentors or association with anything aviation-related, it’s hard for them to stay and to continue to feel that fire that they may have around that. We’ve done that program in getting it widespread out there. Including, if you take the flight, you get a free copy of the software to take the ground school that Sporty’s learn-to-fly course, which is quite a deal. It’s expensive software and every young person can have it up to age 18. We are not developing curriculum for the high schools like AOPA is doing because they’ve got that in place, and we’ve got a wonderful program for that. So, we’re trying to get the kids in advance of that. We’ve been successful. We’ve flown over 2 ½ million kids. You get a lot of gratifying stories where people come back when they’ve started their careers, and it all began because they took a Young Eagle flight.