Damage to the tail of a Citation Mustang after a runway incursion at Houston Hobby Airport.

Runway incursions make the news when there is a spectacular collision, as happened recently at Tokyo Haneda Airport. On Jan. 2, a Japan Airlines Airbus A350 collided with a Japan Coast Guard Dash 8-300 turboprop. All 379 occupants of the A350 evacuated safely after the airliner came to rest, but five of the six people on the Coast Guard aircraft were killed.

The severity of the crash makes runway incursions seem like a major threat to air safety. But the likelihood of an incursion is also important in judging risk, and that is hard to estimate.

To help understand the likelihood, or probability, of a catastrophic incursion accident, the FAA now tracks all incursions at U.S. airports, whether they involve giant aircraft maneuvering in close proximity to one another or just aircraft rolling a few feet past a hold-short line.

Air traffic control staff at the incident airport are required to make Mandatory Occurrence Reports and categorize the event according to its apparent hazard. The A and B categories are incidents they judge to be the most serious. When aircraft narrowly avoid a collision, it is an A. When there is significant potential for a collision and/or evasive action, it is a B.

Most Incursions Are Benign

What the FAA data shows is that most incursions are benign. The 2020 iteration of the “FAA Administrator’s Handbook," for example, showed there were 1,644 runway incursions in 2017, but only five that were categorized as A or B. The more recent “Air Traffic by the Numbers 2023” addressed only major “Core 30” airports, but the pattern was the same. In fiscal 2022, Core 30 airports reported 299 incursions; one was categorized as A, and one as B.

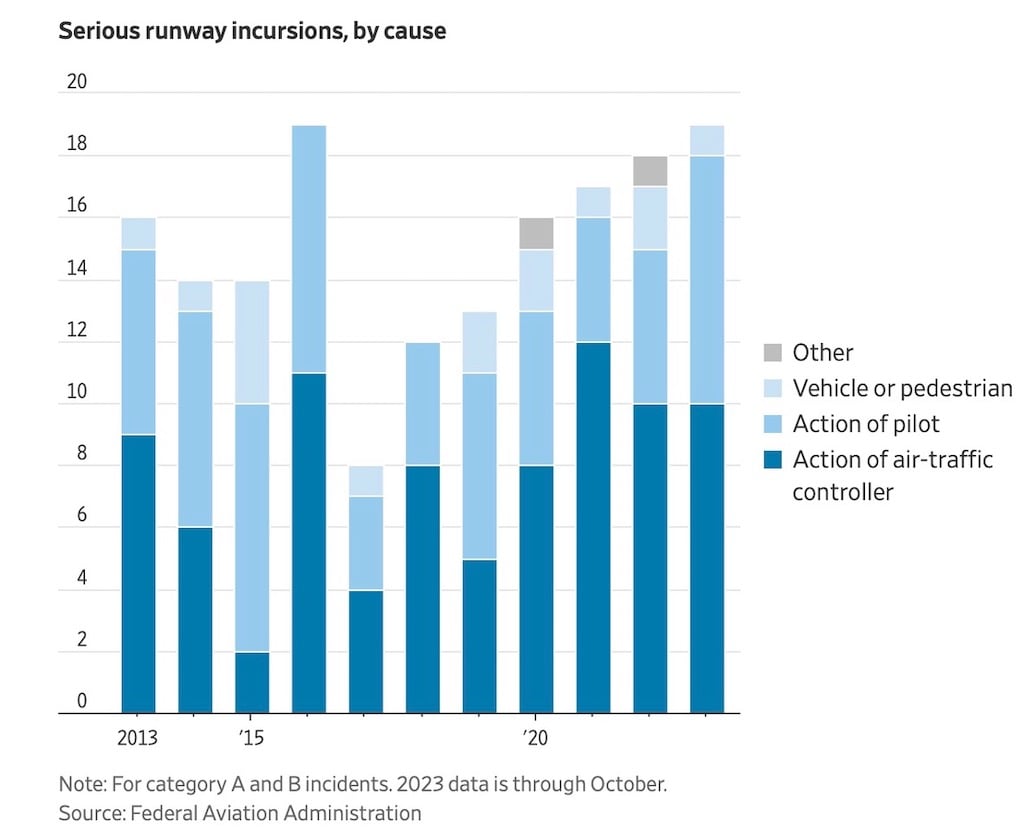

An FAA graphic of A and B incursions from 2013-23 shows a saw-tooth pattern, with eight incidents the low and 19 the high number. There is no discernible pattern or trend. The average incidents over the 11 years is 15.1, so the high of 19 is not statistically very significant. Unless there is an underlying factor driving more incursions, the number will revert to the mean.

The problem with estimating the risk of runway incursions is they are so unpredictable. They are unlike runway excursions, where you can pretty well guess that on a short, slippery runway in windy conditions a runway excursion could happen. You can create mitigations for excursions.

Runway incursions happen at large airports and small, in good weather and bad—with airliners and small airplanes as well as with experienced pilots and novices. They happen when the flow of traffic seems normal and when it is busy. Sometimes pilots miss a clearance, and sometimes controllers create a conflict or fail to see one developing. Airport vehicles rollout on runways and cross them when they are occupied.

The people involved in runway incursions must always be surprised. Imagine the reaction of the pilots of a NetJets Bombardier Challenger 350 suddenly facing an oncoming Cessna 150 trying to land on their takeoff runway. When cleared for takeoff from DeKalb-Peachtree Airport Runway 21L, they were told the Cessna 150 would be departing 21R. What they could not have known was that the Cessna pilot would have a rough-running engine and was going to turn back and fly right at them. The Challenger crew pitched the jet up aggressively and managed to overfly the Cessna by 200 ft.-300 ft.

Then there was the crew of a Hawker 800 twinjet that overflew an airport fire truck just as they were lifting off from Runway 14 at Treasure Coast International Airport in Fort Pierce, Florida. The crew cleared the truck, which was not cleared to be driving across the departure end of the runway, by 50 ft.-100 ft. The pilots likely had some moments of shock, followed by great relief.

A Gulfstream GV crew had to abort its takeoff from Van Nuys Airport Runway 16R after a Beechcraft Bonanza flew over and landed in front of the Gulfstream. Picture the consternation of the Gulfstream pilot as he saw the light airplane cut him off after he had begun his takeoff roll.

After these incidents, two business jets finally came too close and collided. On Oct. 24, 2023, a departing Raytheon Hawker 850XP struck the empennage of a landing Cessna Citation Mustang at William P. Hobby Airport in Houston. The Hawker’s left wingtip and the Mustang’s tail were damaged, but both aircraft landed safely.

Given the unpredictable nature of this type of event, what precautions can we take to prevent damage and injuries? One answer was contained in the testimony of FAA Administrator Michael Whitaker to Congress on Feb. 6. The FAA, he said, will provide more controller training and supervision and deploy tower simulator training systems in 95 facilities by December 2025. There will be runway incursion warning systems and vehicle automatic dependent surveillance-broadcast emitters to cut down on vehicle/pedestrian deviations. The agency is focused on airports that have a history of runway incursions and locations that have incidents of wildlife affecting airport operations.

One initiative that I like but was not mentioned by Whitaker is the agency’s “From the Flight Deck” videos and handbooks. The FAA began producing videos about individual airports roughly two years ago, and the number of installments has increased steadily.

The videos remind me of the Jeppesen 10-7 pages we had at airlines to provide pilots with important operational details about the airports we flew into. Most of the videos concern mid-size airports that host both light airplane and business jet traffic. They provide pilots with excellent airport familiarization.

In FAA announcements and press releases, there are a certain amount of vague promises—but also a glimpse into more substantive actions. Never underestimate the agency’s ability to manipulate statistics in the most favorable way. But runway incursions could be reduced by a concentrated effort on all our parts.