Relationships in the Citation illegal charter accident.

In the second quarter of 2018, former National Air Transportation Association (NATA) president and CEO Timothy Obitts wrote in the association’s Aviation Business Journal that “illegal charter is rampant and something needs to be done.” Illegal air charter operators conduct commuter and on-demand operations without meeting the requirements of 14 CFR Part 135.

NATA joined with the Air Charter Safety Foundation and the FAA to launch a campaign to stop or reduce illegal charters. There is a hotline now for people to report these flights and the FAA has stepped up enforcement.

What we don’t know is how effective these actions have been overall. Has illegal charter stopped happening or is it still pervasive? The U.S. Congress wanted to know that in 2018 and probably still does.

When the current FAA reauthorization bill passed in October 2018, Congress included a provision on illegal charter flights. Section 540 of the legislation required the Secretary of Transportation to analyze the facts of illegal charter and make a report to the appropriate committees of Congress within 180 days of the bill’s enactment.

Two and a half years later, the Department of Transportation responded. The report, written by the FAA’s Office of Aviation Safety, complained about the difficulties it had in identifying and investigating illegal charter operations. The FAA said it needed a better way to collect and manage all of the illegal charter reports that came in, and it hoped to integrate the reports with the Flight Standards Safety Assurance System. That integration had not yet been done in 2021.

That is not to say that the FAA did nothing. It took steps to educate the inspector workforce and FAA legal counsel, created a web page on the subject, and delivered a significant amount of educational material through media outlets. But the agency still does not have a working database it can use to quantify the problem.

Short of a massive IT project that seems to continually recede into the future, there are practical measures the FAA can take to make illegal charters unattractive to potential operators. Way back in 2009, the NTSB sent the agency six recommendations to do just that.

NTSB Recommendations

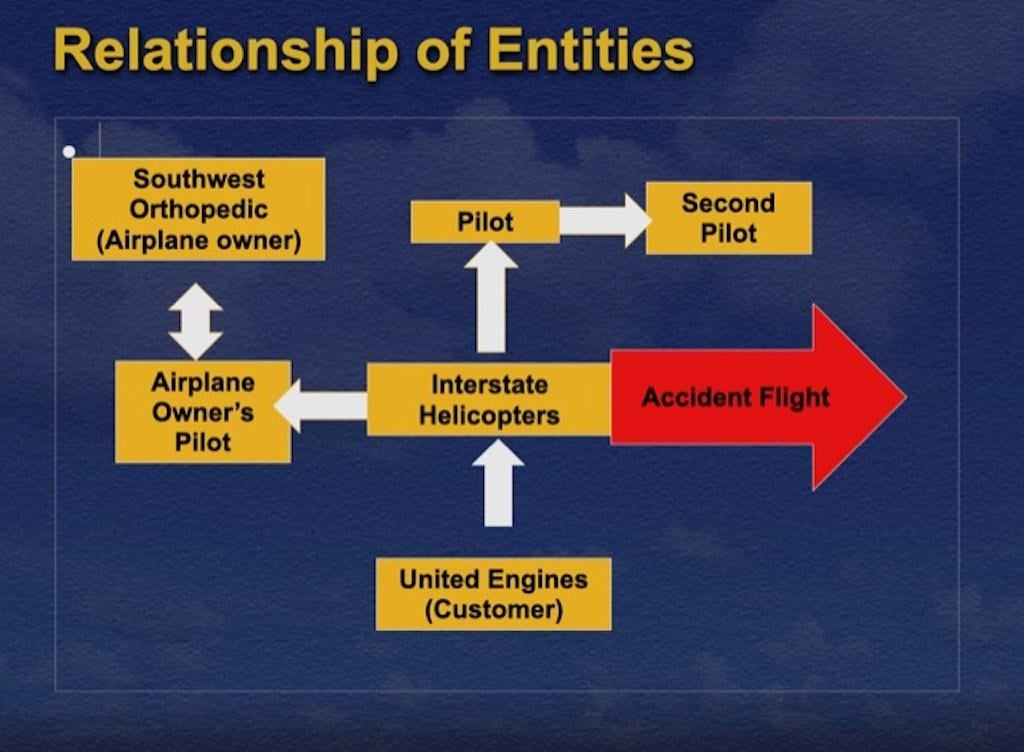

The NTSB safety recommendations, A-09-76 through A-09-81, were the byproduct of an investigation into the March 4, 2008 crash of a Cessna 500 Citation. The cause of the crash was a collision with a flock of American white pelicans. The two pilots and three passengers were killed. The safety board discovered “noncompliant” charter arrangements in the course of the investigation.

The NTSB took a multi-pronged approach to its recommendations. This was because there are multiple parties who must cooperate or collude in order for a charter to take place outside the rules. There’s the pilot, the airplane owner and the client who must agree. Usually there’s also an operator, distinct from the pilot, who makes the calls to organize the flight. The FAA also has an interest, since it has to observe and document any rules infractions.

One recommendation addressed the pilot. It would have required he or she to enter on the flight plan the name of the flight’s operator and the operating rules (Part 135 or Part 91) the flight would be conducted under. If the pilot entered 135 when the flight did not meet those requirements, it would be a clear admission of an infraction. If the pilot entered Part 91 when passengers were paying a fee or fare, that would be another rule violation. Few pilots would want to give the FAA that kind of documentation of an infraction. Few owners would want the tail number of their airplane shown on a Part 135 flight plan if the airplane was not part of a certificated charter operation.

Another recommendation addressed the operator. That person would have to provide the customers a written document describing the terms of carriage, i.e., Part 135 charter. The document could be almost anything—a ticket, a form letter, even an email. This document would eliminate any passenger uncertainty about the flight’s legality, and if untrue, would be a clear way to document another infraction.

To address the client, there was a recommendation for the FAA to keep current and reliable information on its website about the certification status of all charter operators to make it easy for potential passengers to check.

For the FAA itself, there was a recommendation to improve on-site inspector surveillance activities at airports and another to assess why the FAA was unable to identify the improper actions of the operator in the Citation accident.

Finally, there was a recommendation to eliminate the maximum gross weight floor of 12,500 lb. in 14 CFR 91.23, “Truth in Leasing” clause requirement. That rule requires charter operators to notify the FAA of their intent to operate the charter flight before it departs, but it only applies to larger airplanes above the 12,500 lb. limit. The Citation accident aircraft, like many very light jets, was below the weight limit, and having that loophole gives illegal charter operators an incentive to use those very light or personal jets.

The FAA rejected every one of the NTSB recommendations except the one about placing operator certificate information on its website. The rejections were, to me, self-defeating, since they would have eased the task of FAA inspectors, particularly those on the Special Emphasis Investigations Team who pursue illegal charters. I wonder if someone in the FAA just didn’t want a safety agency telling it how to go about its job of enforcing the regulations.

I think there’s a place for relatively simple, pragmatic solutions to safety issues. It isn’t always necessary to wait for the creation of a giant automated program that never seems quite able to do what it was intended to do.