Even though fewer than 100 mi. separate Florida’s Atlantic Ocean beaches and Grand Bahama Island, when looking for something the size of a motor home in a featureless area larger than some states, disappointment and eyestrain are almost assured. And so it was when Wilson Riggan and his two crewmembers landed to refuel.

- A fleet of 125 aircraft, from light planes to jets

- Some 500 volunteer pilots and observers

- Ready to launch 365 days a year

A sport fishing boat en route from Florida was expected to put into the island that morning of May 16, 2019 but did not; the two men aboard had provided no word on their circumstances or whereabouts. The U.S. Coast Guard launched an aerial search with an HC-144 Ocean Sentry crisscrossing the Straits of Florida. When those patterns failed to locate the boat, Riggan was asked to join the effort.

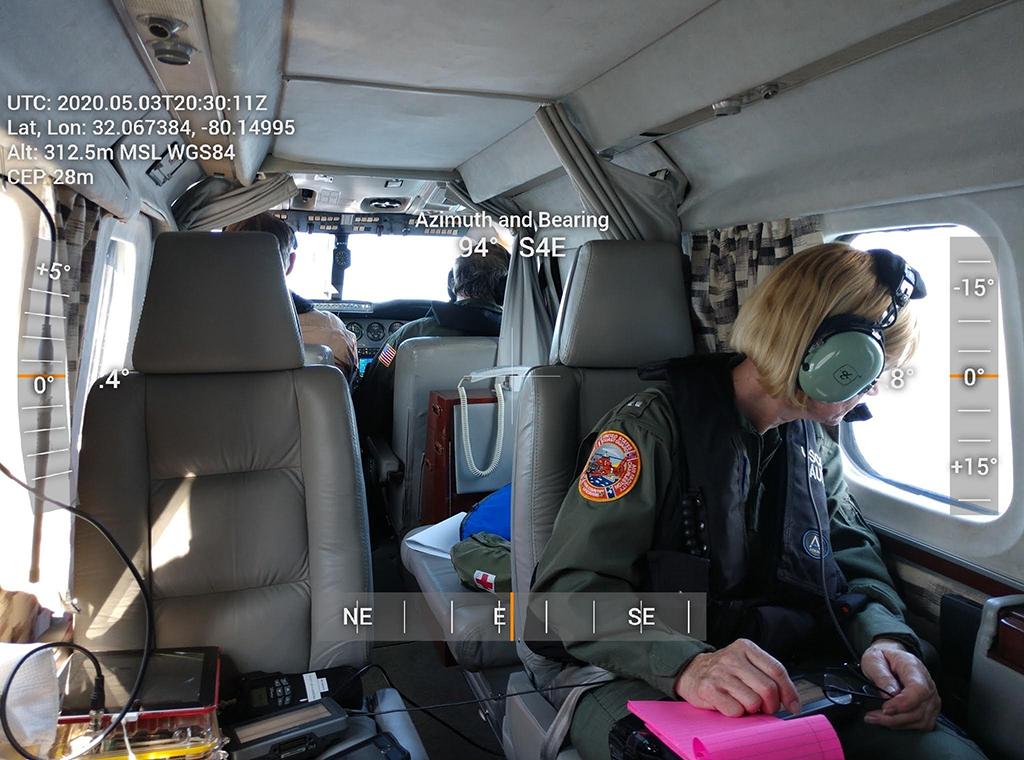

An airline pilot, since retired, Riggan has long devoted a considerable amount of his free time in service to the U.S. Coast Guard Auxiliary. Composed of uniformed, civilian volunteers, the auxiliary supports the regular Coast Guard in missions on land, sea and in the air, excepting law enforcement or military activities. Indeed, Riggan and his crew had been conducting a routine Coast Guard Auxiliary air patrol in his twin-engine Aero Commander 685 when the service alerted him about the missing sport fisherman.

Once refueled, the crew relaunched to continue the hunt. Early in that flight, however, Riggan and his team were told they were searching the wrong section of ocean. It had been learned that the boat had actually departed from a Florida port some 60 mi. farther north of the place originally thought. Accordingly, Riggan’s search was diverted north.

The aircrew was about two-thirds through its prescribed search pattern when a powerboat similar in description to that of the missing fisherman came into view (see photo), adrift in the Gulf Stream. They could see two men in the stern area waving—apparently at them. Keying the aircraft’s marine radio, the searchers asked for the captain by name. The response was quick and affirmative. What was missing was found, albeit disabled for reasons unknown. Upon hearing the news, the Coast Guard immediately dispatched a vessel to assist.

In recalling the day, Riggan says auxiliarists “live for that stuff” and are willing to expend countless hours of effort on the chance they will “get to find the boat or the person.” And the satisfaction that comes with saving someone from potential peril “is why we do what we do.”

When I joined the Coast Guard Auxiliary a few years ago, I had no idea it had an air branch. I have since learned that there are some 500 members in Auxair, of whom 268 are pilots qualified by the service, licensed by the FAA and trained in Coast Guard procedures. They go aloft in a fleet of 125 privately owned aircraft ranging from single-engine light aircraft—which comprise the majority—to helicopters, turboprops and even a few business jets.

Their fuel and maintenance costs are covered by the service when on official missions—expenses that pale when compared to the cost of launching twin-turbine-powered and crewed Coast Guard aircraft on similar missions. It also makes the latter available for other assignments.

In addition to conducting searches for missing boats and people, Auxair missions include responding to reports of flare sightings, unverified Mayday calls, MOMs (for Maritime Observation Missions)—which can involve airborne checks of oil spills, illegal fishing, navigational aids and port security—in addition to transporting service personnel and equipment or even serving as targets for Coast Guard helicopters practicing intercepts.

Such missions can occur any day of the year, but almost all take place during daylight hours and when visibility is favorable. Thanks to those operational constraints and currency and training requirements imposed by the service, Auxair’s safety record is a good one. Its last fatal accident occurred two decades ago when a pilot became disoriented in low-visibility conditions and crashed into the Atlantic off Marathon, Florida, killing himself and an observer. The Coast Guard Auxiliary created a spatial disorientation training program as a result.

Relatively few airborne missions lead to an actual save, but they are celebrated when they do. That is why Riggan was awarded a Medal of Operational Merit at a Coast Guard Auxiliary gathering four months after locating the missing boat. “That was very special,” he says. Surely, a lucky pair of once-powerless boaters would endorse that assessment.

Comments