I used to think of the circle-to-land maneuver following an instrument approach as a necessary evil. We had a lot of airports to go to, in good weather and bad, but not enough straight-in instrument approaches. The cost of installing an instrument approach left us with few options, so we learned to deal with it.

Dealing with it in the U.S. Air Force meant training and checking in actual aircraft while flying as high as possible (up to traffic pattern altitude) and as wide as possible (up to normal traffic pattern width). I no longer think of circling as a necessary evil. Now I think of it as an unnecessary evil made worse by the way we train and check. Worse to the point of being unsafe. I can hear about half of you cheering me on and the other half wondering what all the fuss is about. Allow me to explain.

Before I go any further, let me define “unsafe” for those of you in the business of training and checking in simulators. The FAA, other regulatory authorities and I all agree a safe approach requires the aircraft to be stable no less than 500 ft. above the landing surface. An approach isn’t stable unless the aircraft is wings level, fully configured to land, on speed, on the runway’s extended centerline, and on the specified glide path (usually 3 deg.). Furthermore, you cannot have exceeded 30 deg. of bank on the way to getting there. If you haven’t got all that accomplished by the time you descend below 500 ft. above the landing surface, you are unstable. And unsafe.

Circling Before Simulators Became Clever

Early simulators did a poor job of presenting the airport environment with enough cues to make circling approaches possible, so examiners granted pilots wide latitude. It was almost understood that the turn to the landing runway would be a near-aerobatic maneuver, but so long as we ended up on the runway all was forgiven. As simulators got better, the forgiveness became rarer. Lost on those administering the check was the fact that it is impossible to fly a stable approach off a circling approach at most published visibility minimums. I’ll illustrate that with several examples, but first let me explain how it is that many pilots somehow make it all work out. There are various techniques, but the earliest was with a stopwatch and what many aviators call “the gouge.”

A classic definition of “gouge” is to extort, and I suppose that is apropos here. We pilots would take copious notes after each failed and successful simulator circle and the word spread throughout: when to turn, what offset angle to use, how many seconds to time, and so on. “Do you see the runway?” “Absolutely!” As simulators got better, so did cockpit avionics. So, the gouge has been replaced with wonderful situational awareness (SA) tools, such as airport moving maps and geographically referenced approach charts with accurately placed aircraft symbols.

So, we are learning to improve our SA, which is a good thing. But we are learning the wrong lessons about how to circle. Moreover, we are fostering a false sense of confidence that we will be able to circle in the real world as safely as we do in the simulator. There is no better example than the classic simulator circle exercise: the Memphis International Airport (KMEM), RNAV (GPS) Runway 27, circle to Runway 18R.

The Classic (and Dumb) Simulator Circling Check

In theory, circling north of Memphis is easy because there is a huge ramp that offers visual cues, the approach runway is displaced a half mile from the landing runway, giving you more distance to displace yourself, and there are two other runways leading up to the runway you want to land on. But even with all these advantages, pilots struggle with it until they memorize the gouge or learn creative ways to extend their vision. (More on that later.)

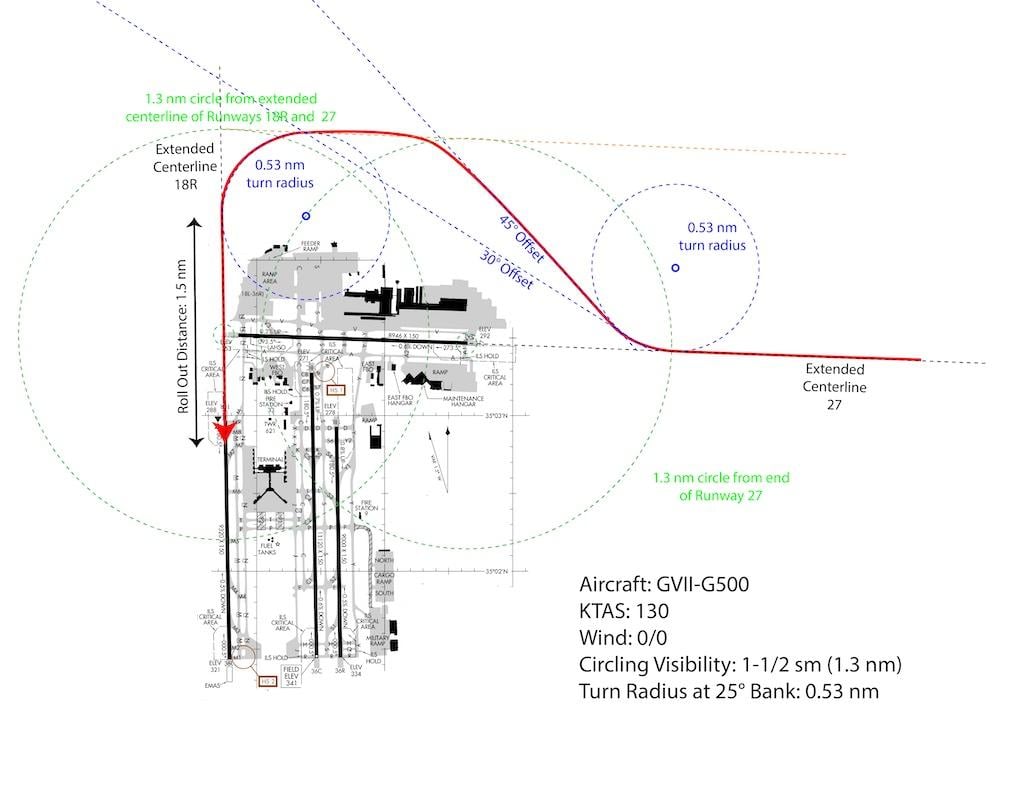

I last accomplished this in a Gulfstream GVII-G500 simulator, a Category C aircraft. A typical approach speed for us at normal weights, no wind, would be 130 KCAS. Our turn radius would be 0.53 nm. The Category C visibility minimum for that approach is 1.5 sm. A statute mile is 15% less than a nautical mile, and that difference is critical. My technique is to turn 45 deg. north once I spot Runway 27 and then turn to base once I have the correct offset. I am fortunate that my aircraft’s avionics help me out with this. In older aircraft, the check airman would light up the ramp to give me the cues I needed.

I was rarely able to do this and roll wings level on final before 500 ft. But the various check airmen almost always ignored stable approach rules, I suppose because they had no choice. I diagrammed the approach and discovered that if flown perfectly, you would roll out 1.5 nm from the touchdown zone. Good job? Almost. A 3-deg. glidepath takes 318 ft./nm, so you would roll out at (1.5)(318) = 477 ft., just shy of a stable approach. But that required perfection on your part. How many flight maneuvers require perfection?

Several years ago, in a reaI aircraft, I was flying into Memphis on a moonless night, just after midnight. The normally busy FedEx arrival traffic was already on the ground, and we had the night sky to ourselves. We were cleared for the ILS Runway 27 and the tower reported the winds at 090/5 kt., which wasn’t optimal. By the time we got to the glideslope, the winds had picked up to 090/15. We told tower, “We can’t land with more than 10 kt. on the tail.” Tower said, “You have the airport to yourselves, circle to the runway of your choice.”

I looked at the right-seat pilot and said, “We’ve never been better prepared to circle, anywhere.” But it wasn’t like the simulator at all; we didn’t see any of the ground references or the approach lights to the other runways. We had to beg the tower to light everything up before we were able to circle.

Of course, this example, and those to follow, are in a jet flying at 130 KCAS. You may have better luck in a slower aircraft, especially in a lower circling category. But I’ve found these results to be typical of Category C, D and E aircraft.

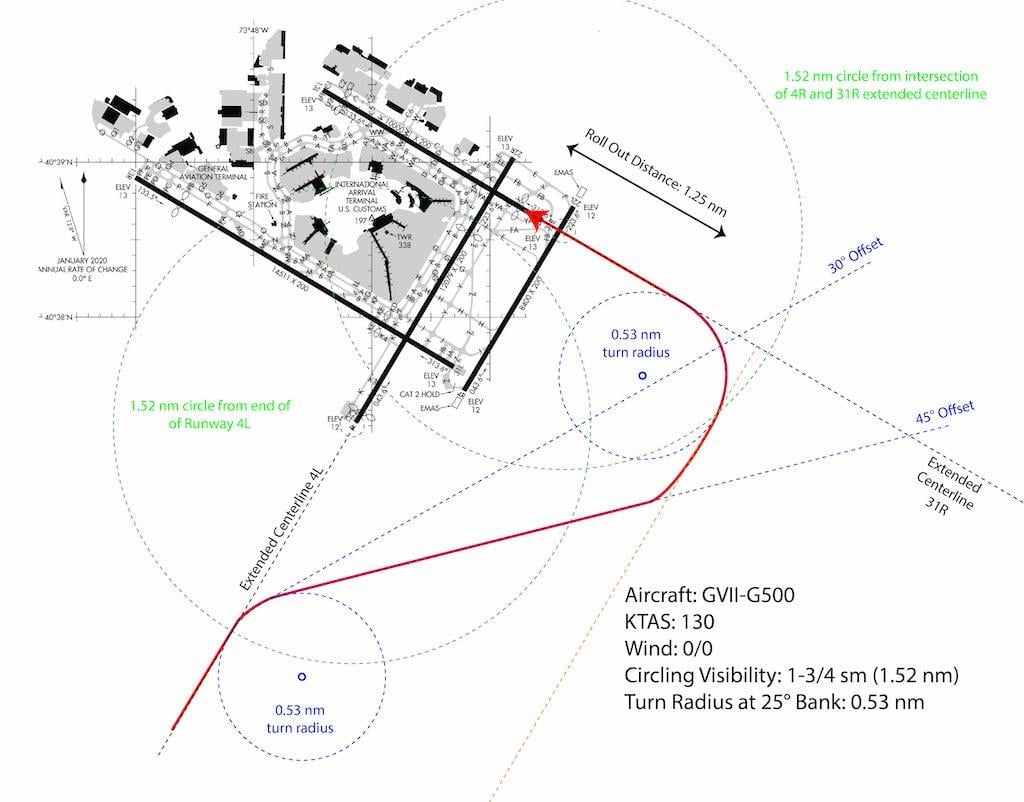

Just as I was learning to distrust the Memphis circling procedure in the simulator, our training vendor discovered a way to make it even worse: John F. Kennedy International Airport (KJFK), New York ILS or LOC Runway 4L, circle to Runway 31R.

Learning to Distrust the Simulator

The simulator circling at KJFK is just like KMEM, but with smaller margins. While you are given 0.25 sm more visibility, you have less offset to the landing runway and fewer visual cues. You end up rolling out 1.25 nm from the end of the runway and that means you will be at (1.25)(318) = 398 ft. Once again, the exercise leaves you unstable at 500 ft.

Most simulator instructors and examiners will grant you a lot of leeway on what constitutes a stable approach during this maneuver. I am usually left to self-critique. “Another unstable approach into Kennedy,” I typically say after landing. “Why don’t you fly a stable approach, then?” I am asked. I admit that my answer is meant to provoke: “I can fly that maneuver at minimums, or I can fly it stable. But I can’t do both.”

Of course, that sparks a heated debate because it is me accusing the examiner of doing something wrong. (I am doing exactly that.) These debates usually end with the examiner saying his or her hands are tied, because the FAA mandates this kind of training and checking of all FAR Part 142 training centers.

The ‘Part 142’ Excuse

My company long ago recognized the circling problem and raised our minimums to 1,000-ft. ceiling and 3 mi. visibility. But at the simulator we are told we must demonstrate circling at the published visibility minimums. When I ask why, I am told it is a “142 requirement.” But the only mention of circling in Part 142 is that if the training center examiner (TCE) will instruct and check students at minimums, he or she must be evaluated at those minimums. There is nothing about we operators. For that you have to look at the airline transport pilot (ATP) and type rating for airplane airman certification standards (ACS). In the ACS we see only that pilots must “execute a circling approach at night or marginal visibility.” The ACS does not define “marginal visibility.” We are also told that an unacceptable risk is “attempting to land from an unstable approach.”

The next line of defense from these TCEs is that if we learn to circle at published minimums at large international airports, it will be easier in the real world. I think they have that backward.

In Part 2, we’ll attempt to solve the circling conundrum.

Comments

I retired as a B744 APD at a major airline, and always disliked teaching and examining circling approaches, given the variables and the teaching and testing requirements, the latter being almost impossible to perform in early generation simulators, and little better in the latest. Fortunately, circling approaches to minimas weren't tested at the final licence ride. Using a gouge was the way most pilots turned in an acceptable performance, and it was generally accepted that you had flown to an acceptable standard if you arrived in the touchdown zone on speed.

After retiring, I took a position as the Director of Operations at a small Pacific Island airline flying B737-300s. Qantas did all our training and pilot certification, and to their credit, their check captains didn't give an inch. All their own crews used a complex gouge for the check ride circling approach.

Nobody told me about the gouge when I went there to do a refresher (I was already endorsed on the B737), and my check was conducted in an old generation sim. Not having been given the gouge, I failed the circling approach - my only flight examination failure in a 40-year military and civil flying career, and extremely chastening.

The home base of my new airline was on an island at the nation's capital city, and the single runway there was an old WWII B17 runway set into an arc of coastal mountains that prevented straight in approaches and required offset circling approaches off a truly diabolical NDB/VOR/DME approach which was probably one of the most dangerous instrument approaches I've ever seen, with a perfectly flown approach only allowing you to roll out wings level on final at 340ft above the runway - nothing stable about that. Circling on a clear night was fun albeit still challenging... but at real monsoonal minimas it became a very nasty black hole exercise turning towards mountains with no real approach lighting (third world, couldn't afford it), no visible airport environment lights (see previous reason), and just one poorly lit village (see previous reason) at the minima, 90 degrees offset from the runway centreline. We had one flight that usually arrived at about 2200, and if the weather was bad and I wasn't the pilot flying that trip, I could never go to bed until I received a call saying the aircraft had landed.

Shortly after taking over the operation, I ordered a new B737-800 with all the goodies (HUD and avionics suite certified for RNP-AR). One week after the new jet arrived, the regulator had approved superb RNP-AR approaches to both ends of the runway, with all pilots certified. Two weeks after the RNP-AR approaches were in operation I wrote an SOP that prohibited use of the old circling approaches in IMC conditions unless the RNP-AR approaches were unable to be flown.

That was when I started sleeping well again.