It always happens when you least expect it. I’ve been called while leaving Best Buy with a new TV. I was once called while riding an exercise bike. I’ve been called at 2 am. There was the time the phone rang when I was signing paperwork for a new car, and I was even called while brushing my teeth to notify me of a limousine crash that claimed 20 lives. I’m, of course, talking about the call to dispatch a Go Team to a crash.

The Go Team schedule runs from 5 pm on Monday to 5 pm the following Monday. When on call, you try to go about normal life, but with the realization the phone may ring, or that you’ll receive a text to notify you of an upcoming call with the Response Operations Center (ROC) in 15 minutes. I learned that accidents don’t happen on days when I had a drawer full of clean clothes. More than once I found myself running a load of laundry when I should have been walking out the door.

In my 15 years as an NTSB board member, I was dispatched on 36 Go Team accidents. As chairman of the agency, I was involved in numerous other calls and meetings at all hours of the day where we made decisions about our level of response. If the accident occurred during normal business hours (seemingly a rarity), the team would gather in the situation room at NTSB headquarters. But it wasn’t always that way.

When Southwest Airlines experienced an emergency landing involving a fatality, I asked someone to turn on the conference room TV to see the latest news. After fiddling with the remote control, we learned that the TV wasn’t wired for cable. I grumbled a bit and a few months later, we had a state-of-the-art situation room with microphones throughout the room for video calls and multiple TVs.

The launch decision starts with a “Chairman’s Call” where key NTSB officials discuss known details of the situation and decide whether a full Go Team will be sent and whether a board member will accompany the team. Depending on the outcome of that meeting, another call may follow to discuss how large the team will be, travel arrangements and the level of support required from other NTSB offices such as media relations, government affairs, transportation disaster assistance (TDA) and general counsel.

We get to the accident site however we can. Oftentimes, the FAA provides use of its aircraft. If FAA lift isn’t available, we fly on airlines. I’ve driven my personal vehicle to a few accidents, and investigators even walked to one once, when a subway train had a fatal smoke event in the subway station in the basement of our building.

We get to the accident site however we can. Oftentimes, the FAA provides use of its aircraft. If FAA lift isn’t available, we fly on airlines. I’ve driven my personal vehicle to a few accidents, and investigators even walked to one once, when a subway train had a fatal smoke event in the subway station in the basement of our building.

Oftentimes we would do a “plant the flag” press briefing outside the FAA hangar, where we would give general information about the launch and let the media know we were headed to the site. Although there usually wasn’t any new information offered, having that media briefing would provide footage that media could show throughout the day until we held a more detailed briefing upon arrival at the scene. At one of these “plant the flag” briefings, I prematurely announced to media that a passenger had perished on Southwest 1380, the emergency landing mentioned above. I didn’t realize I was breaking that news, but it immediately became the news. I then walked into the waiting room of the FAA hangar and saw myself on TV, with a label on the bottom of the screen saying the broadcast was live. I wondered how it could be live if I was standing there watching. Then someone showed me a Twitter post that showed how Southwest stock dropped immediately upon my announcement of the fatality.

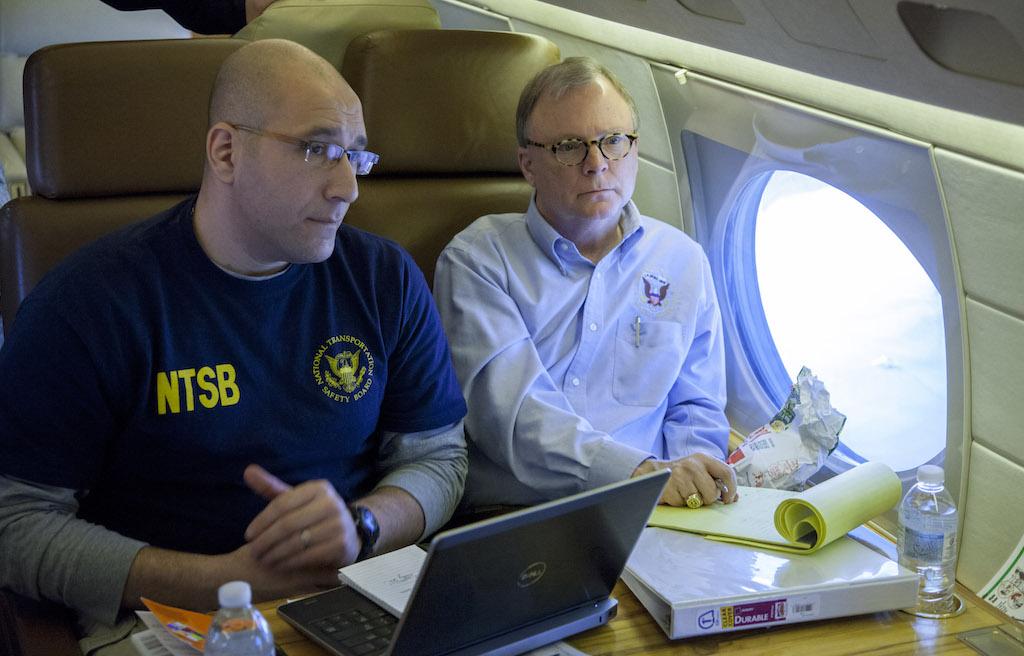

Naturally flying on the FAA jet was the preferred method of transportation. However, it was more than just a method of transportation--it provided a working platform while enroute where the team could start coordinating plans for once we landed. Like with any business aviation operation, FAA’s plane could work around our schedule and take us to airports not served by air carriers. Accidents don’t always happen close to airports served by airlines.

It would not be unusual to have the Go Team met by local law enforcement officials to provide a police escort to the scene. Once we flew into Teterboro for an accident where a passenger ferry boat struck a pier at Wall Street. There were serious injuries--some life-altering. The New Jersey state police provided an escort with lights flashing and sirens blaring, up to the point where their jurisdiction ended at the Lincoln Tunnel. Upon arriving at the tunnel, we saw a white Port Authority pickup truck come out of the tunnel and do a U-turn and go back into the tunnel. The caravan of our rental cars followed that truck, confident that he was our escort through the tunnel, where surely, NYPD police would be waiting on the other side to resume our police escort through the streets of Manhattan. When we got to the other side of the tunnel, we flagged down the truck. “Where is our police escort?” we asked. The driver looked at us oddly and replied in a deep New York accent: “I don’t know what you’re talking about, buddy. I’m just doing my routine patrol through the tunnel.” There was no police escort. We schlepped through Manhattan traffic along with everyone else that day.

It's often wrongly reported that the NTSB board member on scene leads the investigation. Not true. The person leading the investigation is a highly experienced investigator known as the investigator-in-charge (IIC). Board members, such as I was for 15 years, are there to be the face of the investigation, by providing media briefings and meeting with family members and elected officials.

A Go Team consists of NTSB experts in several disciplines, and those experts lead their respective area of the investigation. For an aviation crash, the team would typically consist of NTSB experts in aircraft systems, structures, powerplants, operations/human performance, ATC, survival factors and TDA. Staying behind at headquarters would be experts ready to download and readout the flight data recorder and cockpit voice recorder. Other specialists can be called upon, as needed, such as meteorologist or fire science experts.

Meanwhile, the board member on scene would be preparing to conduct media briefings and interviews, along with meeting with the family groups and elected officials. To conduct these activities required close coordination with the IIC, media relations and TDA to make sure we are providing factual information. As a rule, we wanted to make sure the families heard information from us before they heard it on CNN.

As to be imagined, meeting with family members on the worst day of their lives was absolutely the hardest part of my job. The only solace I could provide was that NTSB was going to find out what happened so others didn’t have to go through what they were going through. After all, that’s the purpose of accident investigation.

Seeing firsthand the devastation that a transportation disaster can leave behind, meeting with family members and seeing their expressions has really driven home for me just how precious life is. As the saying goes, life is a gift. That’s why we call it the present. Never forget that.