In Part 1, we discussed getting ready for training at your new employer.

The first time you take a flight evaluation, you can be forgiven for some nervousness. It is your first time, after all. Of course, you also can be forgiven for some nervousness on every flight evaluation that follows. But the sooner you learn the secret to all flight evaluations, the sooner you will be able to deal effectively with that nervousness. What is the secret? Let me start with a clue. The most nervous check ride I've ever had was the first one I had to give as the flight examiner. Here is the secret:

The primary purpose of a check ride is to evaluate the training program, not the student. If the student fails the check, it is because the training program failed the student.

So, what does this mean for you when learning to fly a new aircraft? With very few exceptions, your instructors want you to succeed and if you are at a loss to understand what is expected of you, the question "what do I need to do to pass?" can yield surprising results. If the evaluators see that you have put in the effort, they will be inclined to give you leeway when needed.

It is tempting to push the academics aside with the excuse you are a "doer" and not a "thinker." But acing the written tests or the oral portion sets you up for the "halo effect." When the examiners see that you put in the effort to learn the material, they will be inclined to say any hiccups in the simulator or airplane are slight aberrations, not patterns of deficiencies. Anyone can have a bad day in the jet, but you have control over your study efforts. Ask for practice exams. If they don't have any, ask for a sit-down session with an instructor for an impromptu quiz. This will give you a chance to test yourself under a spotlight and will help identify any weaknesses that need further study.

An oral exam is your chance to not only show mastery of the material, but confidence in that mastery. Here again, ask for a practice session. If the instructors aren't available, find an already qualified pilot. If none of them are available, try a fellow student.

The flight examination, in the simulator or the aircraft, is likely to have a planned scenario or one of several planned scenarios. Asking others for a play-by-play of their experiences can help you anticipate what you need to be good at. A practice session just prior to the event can also be very helpful.

Through each evaluation event, it is key to understand that the system wants you to succeed, and the system will provide clues to you about what it takes to succeed. But what if this isn't true? We've all heard stories of check rides where the system was out to get you. I think this is extremely rare, but it does happen. If you are certain your evaluator has this kind of mindset, it might be time to ask for a change of evaluators. But be mindful that this might set you up for another evaluator who wants to vindicate his peer. In any case, understand that as long as you did your part, a failed check ride shows the system failed, not you. Add the experience to your learning process and press on.

My last type rating was in the Gulfstream GVII and it was going very well. The aircraft was so new it hadn't yet been certified and the instructors were learning it as we were. We were told most check rides took 2 hr. per pilot and that it wasn't uncommon to need more time. I flew the first session and was paired with an excellent pilot who was making my life very easy. We had sailed through every scenario and only had one event left: the no-flap approach and landing. I looked at the clock and realized we had been at it for just over an hour. The examiner said, "You two are doing so well, you know what is coming next, so let's skip the preliminaries. Just fly me a no-flap landing and we'll call it good." So, I briefed the other pilot that we would simply land with the flaps up and I didn't call for any checklists. I failed to remember that in this fly-by-wire aircraft, the flight control system assumed a contaminated wing below 200 KCAS with the flaps up, unless the wing anti-ice was on. When I let the speed fall below 200 KCAS without the anti-ice the examiner spoke up again, "This was my fault, I shouldn't have led you to this maneuver without the checklist. Please run the checklist." We did so and caught our error. The examiner wanted us to pass. He could have busted us, but it would have been messy, and he had already seen that we knew what we were doing. During the debrief, he said it was the best check ride he had ever given in the GVII.

But what if you do bust the check ride because you had a bad day, because the other pilot had a bad day, or even if the training program let you down? No matter the reason, your employer spent a lot of money to get you qualified. Your employer wants you to succeed and would rather spend a little more money for some retraining and a recheck, rather than having to start over. Having a good attitude at this point will serve you well.

Getting Up to Speed With SOPs

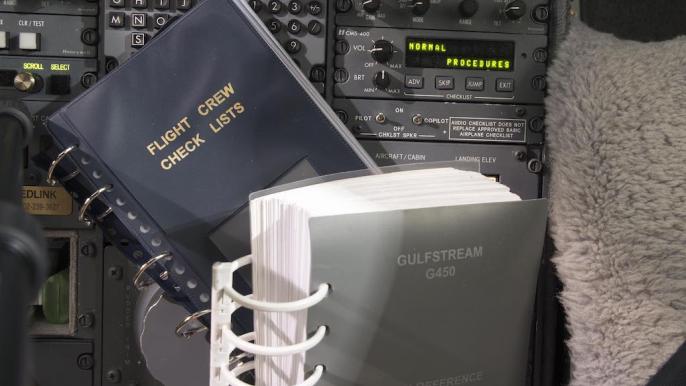

When you come home from type rating training, your next task will be to learn and understand any standard operating procedures (SOPs). Your performance as a crewmember depends on knowing what is expected of you and what to expect from others; this is a fundamental tenet of effective crew coordination. You should never have to guess at procedures. Having a standardized mental model for everything you do will eliminate the guesswork. SOPs provide a consistent, standardized model of each task that must be performed by each crewmember during each phase of flight and during any reasonably anticipated abnormal, non-normal or emergency situation. SOPs must be kept current and may be individually developed by the operator or by incorporating those procedures found in their aircraft operating manuals into their daily operations. Once established, the SOPs must be applied with consistency and uniformity throughout the operation.

Ideally, you will find detailed procedures in your aircraft manuals that are supplemented by your company's operating manuals. Knowing which to follow can be a source of some debate.

- Aircraft-manufacturer-provided SOPs--Depending on the age of your aircraft and how much it has been modified beyond the manuals provided, you may find very detailed and pertinent SOPs in airplane flight manuals (AFMs), aircraft operating manuals (AOMs), pilot operating handbooks (POHs) or other materials issued by the aircraft manufacturer. In some cases, however, these manuals will be out of date, no longer applicable, lost or not up to current best practices.

- Training vendor SOPs--A training vendor may provide a robust set of SOPs that it might offer as a suggestion or as mandatory to pass a check ride. I've been a part of flight departments that adopted these procedures completely, rationalizing that we wanted to "fly like we train." I tend to look at them as suggestions, worthy of consideration after the manufacturer's inputs.

- Company-provided SOPs--Your company should have a stated position on SOPs that could be as simple as, "Follow the flight manual." Company SOPs may also specify everything you need from start to finish.

The first step in learning a new set of SOPs is to ask a seasoned veteran in the flight department about what is expected. Don't be surprised if you get a noncommittal answer; it could be that the SOPs are so ingrained that they never think about them. You might be better off asking a few specific questions:

- Are there any regular briefings prior to starting the preflight or starting the engines, before taxi, before takeoff, before descent, before an approach, before landing, after landing, after the flight is completed?

- Are there any recommended callouts during takeoff?

- Does a pilot who is not the pilot in command (PIC) have the authority to call for a takeoff abort or to execute an abort without the PIC's concurrence? If not, what is the protocol?

- What callouts are expected during approach?

- Who handles the radio, and which radio is normally used for ATC communications?

- How is automation handled between pilots and does this change if the autopilot is engaged? What about the autothrottles?

- How are altimeters set when issued a new setting before the transition altitude or level?

- Is there a specified protocol for cockpit duties when issued a new altitude clearance?

- Are there any airfield specifics that change any of these procedures?

Once you've identified the applicable SOPs, the best way to learn them quickly is to write them down. Keep a notebook with the SOPs and expect to edit as your understanding improves. Your notebook is a work in progress and can be as simple or detailed as needed.

In Part 3, we’ll discuss making a good first impression with your new coworkers.