I think any professional endeavor requires the practitioner to seek outside criticism to further develop skills and to maintain already mastered skills. That is especially true among pilots, where feedback obvious to others escapes us as we are too busy to take note. This can be compounded if the critique is delivered poorly or taken personally.

I was a copilot in a KC-135A tanker flying a precision approach radar (PAR) approach for the first time since initial training, trying to impress upon the aircraft commander that the young second lieutenant assigned to him could be trusted to fly his airplane in the weather. A PAR is straightforward in a small aircraft. The controller gives you a heading and you turn to that heading. The controller gives you descent cues, such as “going above glidepath,” and you adjust accordingly. It isn’t so simple in a large aircraft, such as the KC-135. The aircraft’s sheer size means there is a lot of momentum, and corrections need to be small to prevent them from becoming overcorrections. And that’s where I was on that first flight: “Correcting to glidepath. On glidepath. Going below glidepath.” In short, I made a mess of it. I eventually straightened it all out, but instead of looking like a steady line to the runway, our glidepath looked more like a sine wave of decreasing amplitude.

For the critique, the aircraft commander said, “That’s not how it’s done.” I got better, but that critique and many to follow rubbed me the wrong way. Years later, as an aircraft commander and then as an instructor, I figured out why these kinds of critiques don’t work. They subconsciously equate to the Doug Neidermeyer character in the movie “Animal House,” when critiquing his fraternity pledges: “You are all worthless and weak!” Am I being too sensitive?

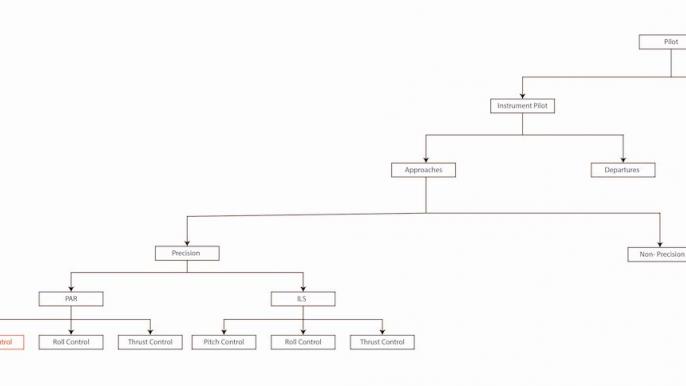

Let’s look at the issue from broad to specific with a diagram of where exactly pitch control falls into the big picture of instrument flying and pilot skills. The drawn diagram breaks down the PAR into pitch, roll and thrust control. Your skill as a PAR pilot breaks down into these elements. You need a similar skill set for an instrument landing system (ILS) approach and together they make up your precision approach capabilities. Alongside this, you have similar non-precision approach skills, which are not shown for simplicity. Now we have diagramed your instrument approach skills. Further up the tree we have departure procedure skills. Combined, these are what make you an instrument pilot. Of course, there are many skills needed to be a pilot, but we have isolated the very specific skill of controlling your pitch during a PAR instrument approach.

My bungling of the PAR amounted to poor pitch control; I wasn’t adjusting the aircraft’s pitch as precisely as needed. I was simply moving the nose of the aircraft up or down in response to new trend information. I should have kept the pitch steady and made adjustments to a new value as needed. For example, if 3-deg. nose-up pitch gave me a “going below glidepath,” I should have picked a higher pitch like 5 deg. nose up, kept it there, and waited for new trend information. A better critique would have been to say: “You tend to overcontrol your pitch changes. You should reduce the amount of each pitch change and give it some time before making the next adjustment.”

A specific observation and recommendation, instead of a general comment without a suggestion, ends up being more useful and less threatening. Saying, “That’s not how it’s done,” tells me that I don’t know how to fly a PAR, I don’t know the first thing about precision approaches, I am a lousy instrument pilot and, yes, I am a worthless and weak pilot. Overly dramatic? Never underestimate your subconscious’s ability to take things like this personally.

As pilots we need to be in the business of giving and accepting critique. We should of course learn to accept sincerely offered criticisms in the spirit they are offered. But we can make these critiques more effective by making them more specific. Let’s say you didn’t end up exactly on the extended centerline during your last visual approach. If I were to say, “You overshot final,” you could interpret that to mean I think you were not paying close enough attention to the wind and are a lousy visual pattern pilot. In fact, maybe you are a lousy pilot and human being! But if I said instead, “The wind pushed us across final. I wonder if an earlier turn was called for,” I have removed the personal “attack.” I have narrowed our focus to one of the possible issues, the wind, and a possible solution.

Guts

Depending on how much mental scar tissue you have accumulated over the years as a pilot, you could be arguing that all this talk of empathy and tact is well and good, but what if the S.O.B. in the left seat is trying to fly you into a mountain? Surely there are times when you must push back and get the other crewmember to change his or her course. Yes, and that is where the real art of empathy and tact become invaluable. A CRM academician will tell you to start with inquiry, move on to advocacy, and then finally to assertion. OK, fine and good. But what does that really mean?

Whenever I study aircraft accident reports I remind myself that with very few exceptions, no pilots start the day thinking, “Today I will crash an airplane.” But many of the pilots in these reports got caught up by events and forgot things they knew that could have saved the day. A good copilot inquiry could have brought them back into the fold.

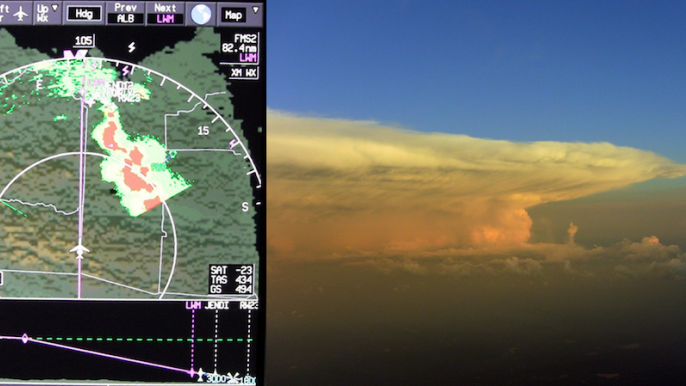

After a year as a KC-135A copilot, I was paired with an aircraft commander with a reputation for rash decision making. On our first flight returning from an oceanic trip, he was tired and anxious to get home, but we had a thunderstorm parked between us and our base. He directed me to request a lower altitude so we could fly below the weather.

Step One: Inquiry. “Sir, is flying under a thunderstorm safe?” I thought that would do it, but it did not. His answer: “I’ve done this before, don’t worry about it.”

Step Two: Advocacy. “Sir, I think we have the fuel to hold and wait for the system to move, to fly upwind around it, or to divert.” His answer: “It would take an hour to fly around it and we’re not doing that.”

Step Three: Respectful assertion. “Sir, I read that the vertical downdrafts in a thunderstorm can exceed any airplane’s climb capability. I think I would rather be late than the first to arrive at the scene of an accident.”

That did it and although he was complaining the entire time and worried about what the squadron would say about our late arrival, he was pleasantly surprised that other aircraft followed our lead and we received praise for our superior judgment. I think had I started off with “Your plan will lead to an accident,” he would have thought I was accusing him of being an unsafe pilot and he would have just dug in his heels and pressed on. But using the inquiry, advocacy, respectful assertion process led him to my position as if it were his own.

What About the Captain?

So far in this series of “Better,” we have looked at how to become a better student, a better pilot and a better crewmember. I believe each step can be applied to any crewmember, even the captain. The next in our series, “Being a Better Captain,” is more than just how to be a better crew leader, it is also about how to be a better leader. (As aircrew, we are all leaders.)

Comments