Letters From Our Readers, March 7, 2022

WATER MANAGEMENT

Your article “Methods of Curbing Contrails Are Taking Shape” (Jan. 10-23, p. 32) makes a point that caused me to question some current aviation technology trends. The article notes that contrails are responsible for over half of the net atmospheric warming effects of aviation, specifically, surpassing the effects of CO2. Given this surprising fact, does it make sense for technologists to be pursuing hydrogen fuel cells to power electric engines in aircraft? Will the water produced by the fuel cells be stored onboard, used for onboard water needs, or will some or all of it be dumped overboard to reduce weight? If the latter, does that not reduce the advantages of moving from fossil fuels?

Craig Price, Carmel, Indiana

Editor’s note: Water management is a key aspect of hydrogen fuel-cell system design for aircraft. Initially, fuel-cell-powered aircraft are expected to fly at lower altitudes where contrails are not an issue, but for higher altitudes, techniques such as storing the water produced in wing tanks for later dumping are being considered. However, research suggests any contrails formed by water vapor emitted by fuel cells will be short-lived because they will form larger ice crystals that fall faster.

DATA TO JUSTIFY CO-PILOTING?

As a retired captain from a major American airline, I read “Flying Solo” (Jan. 24-Feb. 6, p. 50) with interest. Can a single-piloted commercial transport be operated with an equivalent or greater level of safety? If the answer is “yes,” then there is no reason not to have a single pilot.

Given the advances in computers, avionics and aircraft design, it is difficult to argue against this proposition. Examples, which would have been difficult to imagine a decade ago, include the Garmin Autoland, available on select G3000s, that will automatically divert and land an aircraft with the push of a single button and DARPA’s Alpha-Dogfight Trials, in which a computer won every engagement against an experienced F-16 pilot.

It is easy to imagine flying with the perfect nonhuman co-pilot—one that would recognize problems instantly, respond faster than any human, be totally knowledgeable in every aircraft system and never have a “bad day” because of sleep or personal problems.

The question isn’t whether automatic systems should be on the flight deck but whether there is actually sufficient data that would justify keeping a second human there.

Guy Wroble, Denver

TECH SUPPORT

As a former cockpit equipment engineer and aviation psychologist, I found “Flying Solo?” (Jan. 24-Feb. 6, p. 50) interesting. I helped design the Cessna Citation flight deck, which was always intended to be flown single-pilot. And as the senior FAA human performance scientist in 1981, I warned the FAA administrator of potential hazards with proposed two-pilot, automated jetliners.

- Single-pilot airliners should require even greater caution as well as the development of several innovative technologies and procedures, including:

- Artifical-intelligence-based synthetic co-pilots tested in realistic airline environments with actual line pilots.

- Pilot incapacitation recovery equipment that has demonstrated its capabilities in all expected environmental and weather conditions.

- Ground-based control of aircraft refined to allow a “mission control” operator to rapidly assume control when necessary.

- Installation of multiple video cameras to enhance mission control situational awareness of onboard and external events in real time.

- Equipment allowing cabin crew to quickly contact mission control.

- Systems to monitor pilot health and fatigue as well as better medical and cognitive testing of airmen.

- Crew resource management training refined to include flight deck, cabin and mission control personnel.

Alan E. Diehl, Albuquerque, New Mexico

REFUELING REQUIREMENTS

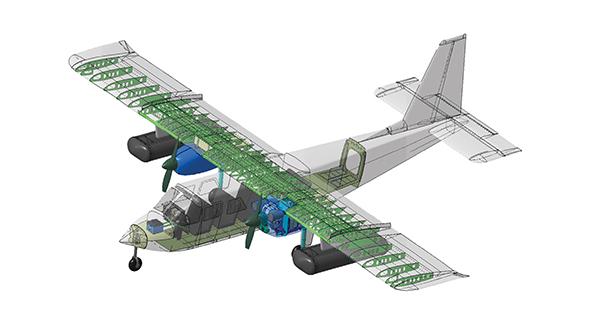

CAeS CEO Paul Hutton, commenting on the development of the hydrogen-electric-propulsion Britten-Norman Islander (“Big Interest but Small Start for Hydrogen Propulsion Project,” Jan. 24-Feb. 6, p. 42) states: “The Islander is a fixed-wing bus that is used in difficult geographies, but its Achilles’ Heel is the cost and availability of avgas.”

The aircraft is being designed for 60-min. endurance plus 45 min. reserve, which would indicate it will need to refuel at most if not all of its destinations.

Which begs the question: How costly and available will hydrogen be in those same geographical locations?

Roger Curtiss, Deer Harbor, Washington

KOOL-AID

Your magazine has elected to talk about a relatively immediate cessation of hydrocarbon fuels, replacement of petroleum with “no carbon” fuels, support of hydrogen propulsion and the naive belief in climate change.

Wait until you fully realize how nearly impossible hydrogen fuel is to produce and transport. How would you build a hydrogen tanker truck?

Earth doesn’t have nearly the mass to hold hydrogen down, and it’s the tiniest element, which will escape the hardiest seal. Transportation is a nightmare, and how are you going to make it—in situ? And battery-powered airplanes? You’ve drunk the Kool-Aid.

William Wooley, Beaumont, Texas

CORRECTION

“Broken Links” (Feb. 7-20, p. 16) should not have stated that Steve Horsburgh, director of product development at Curtiss-Wright, had managed the Pentagon’s Link 16 deconfliction server for the Joint Staff.