南米における都市型エアモビリティの発展は実現するか?| Could Urban Air Mobility Enable Growth In Latin American Cities?

都市型エアモビリティに関しては、ひとつのサイズが誰にも合うとは限らない。コロナ危機から回復する方法が世界各地で異なるのと同様、エアタクシー市場も様々な方向への進化が考えられる。

コロナ禍による在宅勤務のトレンドが続けば、アメリカの大都市における交通渋滞が戻ってくる日も遠のき、結果的にエアタクシーの需要も下がることになると、一部の市場関係者は指摘している。ただし、アメリカ以外の国でもそうなるとは限らない。

コロンビアのあるスタートアップ企業は、南米における都市型エアモビリティ(Urban Air Mobility :UAM)について異なる未来像を描いている。同地では、治安維持や旅行者の安全性確保、崩壊したインフラの再構築と都市の成長の両立といった問題に政府が対応できておらず、これらがUAMマーケット成長の原動力になる可能性がある。

「UAMがアメリカでどのように普及したとしても、南米で同じように再現することはできないだろう。なぜなら、都市インフラ・政府の能力・社会における矛盾など、数多くの問題が存在するからだ」と語るのは、ボゴタに拠点を置くVaron Vehicles社の創業者兼CEO・Felipe Varon氏だ。

「これらの違い全てが、我々が求める機体性能や、開発を目指している空域統合アーキテクチャ、バーティポート(VTOL用発着場)の設計などに影響を及ぼす」と彼は話す。アメリカとは、政治体制や法規制、気候に至るまでまったく異なるのだ。

「これらの障害をどのように乗り越えるか考えた時、アメリカの外で始めるべきだと気付いた。物事を安全に進めるためには、先駆者と同じ学習曲線を一歩ずつたどっていくしかないことは分かっていたが、アメリカの外から歩き始めた方が、より効果的で、より早く、安上がりになるだろう」と述べた。

彼は、ヨーロッパのある国から同社のUAMを実装する依頼を受け招待されたが、むしろ母国でスタートする方が「巨大な」アドバンテージがあることに気付いたという。「政府と航空当局の支援を得て、当社として初のインフラハブをコロンビアで構築することになった」と同氏は語る。

さらに、「こちらで進めた方が早く、認証プロセスや飛行試験、そこから正式サービス開始に至るまで、明らかに安上がりだ。つまり、これは(先進国と)同じ学習曲線をたどっている。我々は安全を最優先するので近道は使わない。安全性への認識も同じように重視しているからだ。安全性も確保されなくてはならない」と続けた。

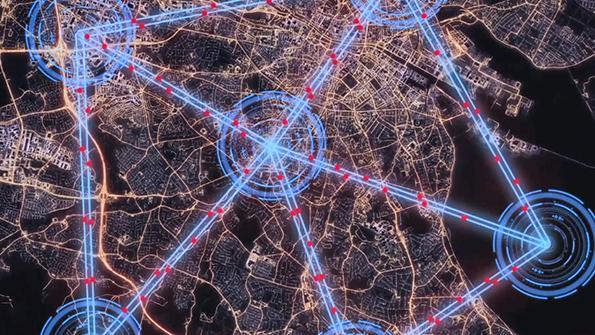

同社はUAMの機体を開発しているわけではない。同社の狙いは、あらかじめ設定され、航空管制に影響を与えずUAMが飛行できる低高度の専用航路と、それで結ばれたバーティポートで構成される交通システムだ。

「機体はあくまで目的を達成するための道具にすぎない。真の目的は都市における交通問題への対処だ。アメリカを含む先進国の交通問題と、途上国における交通問題はまったくの別物だ」とVaron氏は語る。

さらに同氏は、「アメリカでは、交通問題=渋滞、つまり時間のムダに過ぎない。こちら(途上国)にも同じ問題はあるが、他にも様々な要素が付きまとっている。環境汚染・損傷したインフラを復旧できない政府・犯罪…。一言で言えば、アメリカよりはるかにひどい」と付け加えた。

また、距離感も大きく異なる。Varon氏の考えでは、サンフランシスコのベイエリアでUAMを有効活用するには50~60マイル(約90km)の飛行が必要になる。一方、南米で最大級の都市であるボゴタでも、端から端の距離は15~16マイル(約25km)に過ぎないが、その移動には2時間半かかることもある。

「我々が構築するべきネットワークにおいて、バーティポート間の最長距離はせいぜい6~8マイル(約11km)だ。これが機体性能や、空域統合アーキテクチャ、メンテナンス頻度、バーティポートの設計に影響を及ぼす」と彼は述べた。

さらに、「これが、先進国で開発されたUAMを途上国に流用できない理由だ。同時にこれは、我々が自国の政府から支援を受けられる理由でもある。つまり、政府は自国の問題に対処するためのソリューションで、世界をリードすることができると気付いたわけだ」と語った。

Varon氏がUAMを用いて構築しようとしているインフラビジネスには4つの柱がある。1つ目は交通、他3つはエネルギー・不動産・データで、これらも収益源になるだろう。同社の目論見は、インフラのハブをフランチャイズ化することだ。

「我々がこのような俯瞰的な見方をするのは、都市の成長につなげることを意識しているからだ」と彼は話す。バーティポートを都市の外側に設置することで、人口圧力を緩和することができる。そして、「特に、政府が鉄道や地下鉄網を整備するほどの力を持たない南米では、物理的なインフラ整備をすることなく、都市外縁部の成長をもたらす手段を我々は提供することができる」と付け加えた。

Varon氏は、インフラのハブであるバーティポートこそが「魔法の場所」になると語る。周辺に整備される商業エリアや住宅地の開発が不動産ビジネスを促進し、UAM運航に必要な発電・送電・蓄電システムは地域への電力供給にも活用できる。さらに、気象や利用者に関するデータをはじめ、UAM運航により収集された各種データも価値を持つだろうと同氏は語る。

彼は「ハンバーガー・フライドポテト・ドリンクを組み合わせ、マクドナルドの1号店を立ち上げる」ことに例え、自社がコロンビアにおける最初のUAMインフラを建設する段階に入ったと述べた。「これからの5年で運航を始めることが目標だ。それが我々にとってのマクドナルド1号店になる」と彼は話す。

資金調達のシードラウンドの開始に合わせ、Varon氏はUAM機体メーカーやサブシステムメーカーに対し、コロンビアで開発することが認証や運航開始への近道になることをアピールしている。同氏は「全ての質問に答えられるわけではない。しかし、我々がどこを目指し、なぜその方向に進むべきかという問いかけには、明確なアイデアを持っている」と締めくくった。

以上は、Graham Warwickが Aviation Week & Space Technologyいた記事です。 Aviation Week Intelligence Network (AWIN) のメンバーシップにご登録いただくと、開発プログラムやフリートの情報、会社や連絡先データベースへのアクセスが可能になり、新たなビジネスの発見やマーケット動向を把握することができます。貴社向けにカスタマイズされた製品デモをリクエスト。

One size may not fit all when it comes to urban air mobility. As different regions of the world recover from the COVID-19 crisis in different ways, the market for air taxis could evolve in different directions.

If working from home continues after the novel coronavirus pandemic subsides, some market observers contend, then gridlock could be slow to return to the streets of the most congested U.S. cities and demand for urban air taxis could be delayed. But the same might not hold true outside the U.S.

A Colombian startup paints a different picture of the need for urban air mobility (UAM) in Latin America, where the safety and security of travelers, and governments’ inability to rebuild crumbling infrastructure and grow their cities, could be the major drivers.

“How UAM is being worked in the U.S. will not be able to be replicated in Latin America. There are many reasons that have to do with city infrastructures, government capabilities and society paradigms,” says Felipe Varon, Bogota-based founder and CEO of Varon Vehicles.

“All of these differences impact the vehicle performance that we are looking for, the airspace integration architecture that we need to develop,” he says. “It impacts the vertiport design.” Bureaucratic, regulatory and even climate conditions are also different outside the U.S.

“We were looking at how to overcome those barriers, and we knew that the way to do it was to begin implementation outside the U.S.,” Varon says. “We knew the answer was to walk that same learning curve we all have to . . . to make these things safe. . . . [But starting] the walk outside the U.S. was going to be better, faster and cheaper.”

Varon says the startup was invited by a European country to implement its UAM system there but instead saw the “huge” advantage of starting in its home country. “We are implementing our first infrastructure hub in Colombia with the support of the government and the aeronautical regulators,” he says.

“It’s faster to do it here, and it is definitely cheaper to do the certification process, flight testing, all the way into service,” Varon says. “So it’s that same learning curve. We are not going to cut any corners because safety is a priority, and the perception of safety is equally important. It has to be achieved.”

The startup is not developing a UAM vehicle. Instead it is offering a transportation system that consists of vertiports connected by defined, permanent low-altitude flight lanes along which vehicles can fly without burdening air traffic control.

“The vehicles are tools to achieve a goal,” Varon says. “The real business is an urban business. It’s a mobility issue. And the mobility problem in the U.S. and the developed world is entirely different from the mobility problem in the developing world.

“In the U.S., the mobility issue is reduced to the traffic problem—the loss of time,” he says. “Here we have the same problem, but with a whole bunch of other layers on top of that. We have pollution. We have the inability of governments to renew defective infrastructure. We have criminality. In a nutshell, it is really much worse here than in the U.S.”

There is also the difference in scale. In the San Francisco Bay Area, for UAM to make sense, Varon says, trips need to be 50-60 mi. Bogota, one of the biggest cities in Latin America, is just 15-16 mi. across but it can take 2.5 hr. to cross the city, he says.

“With the network we need to lay out, the longest trip between vertiports is going to be 6-8 mi.,” Varon says. “That impacts the performance that we require from the vehicle. It impacts the airspace integration architecture, the maintenance cycles, the design of the vertiports.

“That’s why you cannot replicate UAM from the developed world in the developing world,” he says. “And that’s why we are being supported by our government. Because they have realized they can lead the world in creating a solution to a problem that is endemic to us.”

Varon’s approach is to use UAM to create an infrastructure business that has four pillars, one of which is transportation. The others are energy, real estate and data, which would also generate revenue streams for the business. The startup’s plan is to franchise the infrastructure hubs.

“The reason we take this high-level view is because our overall pitch is about city growth,” Varon says. Vertiports can be located outside cities to alleviate the growth pressure. “Especially in Latin America, where governments are not able to provide that connectivity with rail or metro systems, we can provide a way to generate growth in the surroundings of cities without the need for physical infrastructure,” he adds.

The vertiports or infrastructure hubs “are where the magic happens,” Varon says. Commercial and retail space and housing development at and around these hubs will drive the real estate business, while the energy generation, transmission and storage needed for UAM can also supply the local community. Weather, passenger and other data gathered during UAM operations also have value, he says.

Likening what his company is doing to “bringing the burger together with the french fries and drink to make the first McDonald’s,” Varon says the startup has entered the construction phase for its first UAM infrastructure in Colombia. “Our plan is to be operating within the next five years. That’s our first McDonald’s,” he says.

Having launched its seed-financing round, Varon is talking to UAM vehicle and subsystem manufacturers, presenting its argument that working with Colombia could offer a quicker route to certification and operation. “We don’t have the answers to all the questions,” Varon says. “But we do have a clear idea of where we need to go and why we need to go that way.”