Opinion: A New Approach To Resilient Performance In Aviation Safety

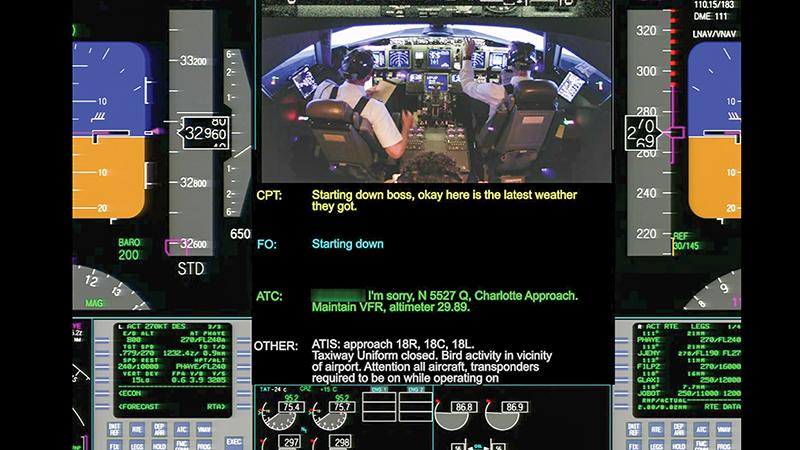

An Embry-Riddle and NASA team analyzed captioned video from simulator sessions to identify positive pilot performance.

Credit: Embry-Riddle

While aviation tends to focus on learning from mistakes—and rightly so—the potential to learn from positive outcomes often goes unrecognized. Jon Holbrook, a cognitive scientist specializing in aviation at NASA’s Langley Research Center, says that pilot intervention has “kept millions of flights...

Opinion: A New Approach To Resilient Performance In Aviation Safety is part of our Aviation Week & Space Technology - Inside MRO and AWIN subscriptions.

Subscribe now to read this content, plus receive full coverage of what's next in technology from the experts trusted by the commercial aircraft MRO community.

Already a subscriber to AWST or an AWIN customer? Log in with your existing email and password.