When Will Africa Fully Embrace Its Air Transport Potential?

There are only so many times it is possible to highlight the prospects for growth in aviation across the African continent while still maintaining enthusiasm that the huge potential can be realized.

Africa represents the last frontier for aviation development, but impotent government transport strategies and ongoing protectionism practices continue to limit its success. There is a mild hope of regulatory progress, while perhaps the greatest optimism attaches to some very persistent attempts to expand LCC operations in the region.

The high taxation that almost all African governments impose on aviation fuel means that the operating costs of the local airlines are among the highest in the world, while costly monopolies among service providers at the different airports continue to blight the industry.

However, airline failings across the continent cannot simply be dismissed on those grounds. Poor management practices and government restrictions on operational freedoms have severely impaired the natural progression of the industry.

There has been progress though. While governments continue to push for their own flag carriers, increasingly these are being facilitated through partnerships with an established airline partner—a model that has already been demonstrably successful in some markets. Airlines are also starting to look beyond national borders and work on wider regional growth.

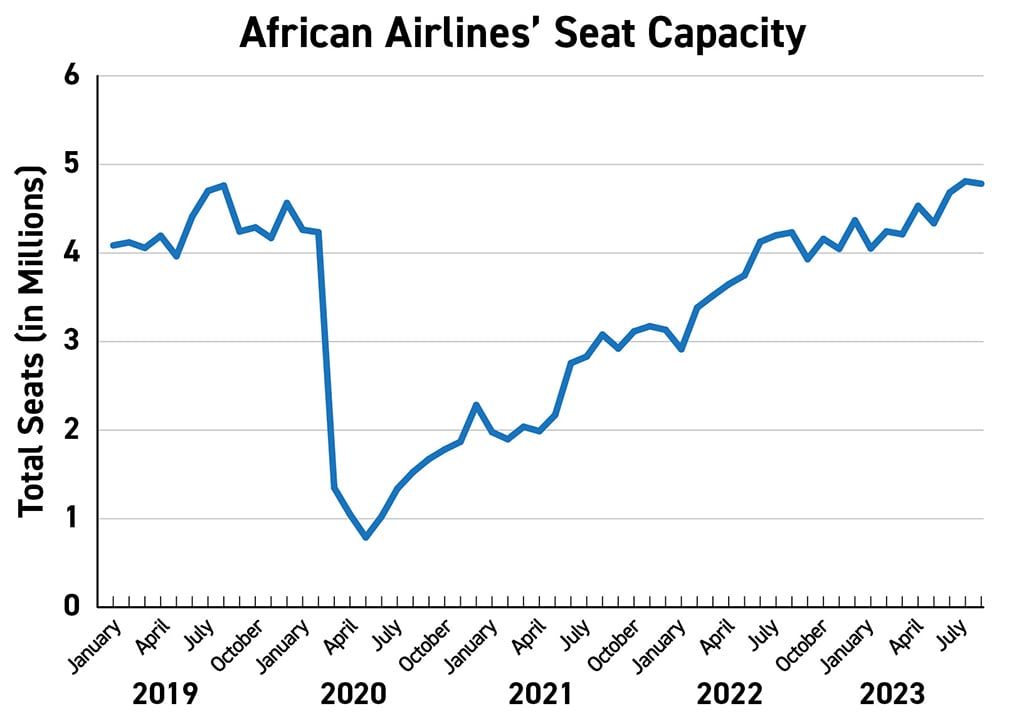

As with all regions, the COVID-19 pandemic has altered the continent’s aviation landscape. But Africa was quick to recover its air services and from around mid-2022 capacity was within small margins of pre-pandemic performance. In 2023, capacity has consistently been ahead of 2019 levels and advanced schedules suggest this will continue through the remainder of the year.

South African Airways may have the same name but now has a very different prognosis. But its sabbatical has provided a void that others have been quick to fill. Still, Ethiopian Airlines remains the standout performer and is growing rapidly with its cross-border model. Royal Air Maroc has also emerged stronger, supported by its membership in the oneworld global alliance.

Ethiopian Airlines is the market leader in Africa, accounting for more than a 9% share of total seat capacity and a figure that continues to grow. Ethiopian Airlines is now more than 50% larger (based on seat capacity) than EgyptAir and more than double the size of all other African operators. At the beginning of the last decade Ethiopian was smaller than all these airlines.

Africa’s current commercial aircraft fleet consists of 2,900 aircraft, according to the CAPA Fleet Database, and there are only just over 150 aircraft on order from African airlines. And it is Ethiopian Airlines that has the largest order book, ahead of the Nigerian operators Air Peace and Arik Air.

An opportunity to grow the LCC sector in Africa is obvious. In half a decade, LCC share of seat capacity within Africa has almost doubled, according to CAPA and OAG data, and as of early August 2023 accounted for around one in five seats. This is still a modest figure and consists almost entirely of services connecting North Africa with Europe, albeit growing across many markets. There are still several major markets in Africa that have no, or virtually no, LCC presence.

Is Liberalization Likely?

The capital of Côte d’Ivoire, Yamoussoukro, is still less known for its aviation connectivity than for giving its name to the declaration that promised so much for aviation in Africa but has ultimately delivered so little.

The January 2018 launch of the Single African Air Transport Market (SAATM) is certainly progress, but it threatens just to be yet another unfulfilled landmark in African aviation, unless the industry works closely with governments to break the barriers that are restricting the continent from reaching the levels of which it really should be capable.

SAATM is a fine expression of goals, but now, over five years since its launch, it unfortunately is being compared with the supposedly liberalizing Yamoussoukro Decision long before: It could simply turn out to be yet another unfulfilled landmark of aspirations in African aviation.

To recite the decades-old painful cliché, Africa’s potential remains massive. But until governments recognize the wider benefits an efficient aviation system can bring, with its impact on economic development, that persistent situation will continue. An important first step would be to remove counterproductive taxation systems, but much remains to be done on the essentially protectionist regulatory front.

Africa remains a market of huge potential but even larger challenges. The outlook for the future appears to be mostly more of the same, but with some glimmers of hope.