Clay Christensen, an outstanding academic and business thought leader, passed away last month. He was the father of the disruptive innovation theory that became widely popular in the last two decades, including in the aerospace industry. I was lucky enough to have him as a professor at Harvard Business School at the time when he was still fine-tuning his theory and before he became a best-selling author with his first book, The Innovator’s Dilemma.

Christensen’s mind was as brilliant as his heart was compassionate. His fundamental premise was that innovation could become a much more predictable and manageable science if business leaders would only focus on the right parameters, such as the resource allocation process, technology performance trajectories and value chain dynamics of modularity and integration.

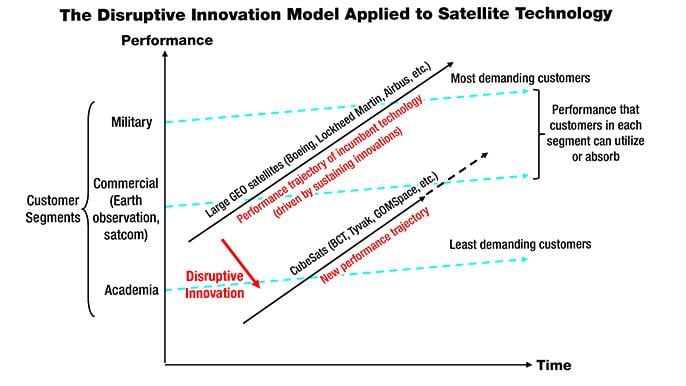

The main insight from his theory was that incumbents in any industry tend to end up overshooting what their customers really need. By doing so, they open the door to new entrants that disturb the way traditional players have been making money by offering a typically less sophisticated technology but one better fitted to the needs of less demanding customers.

The aerospace and defense industry, despite its long history of government-protected markets, has not been immune to this phenomenon. The most obvious example is the way low-cost airlines have redefined the economics of air travel, by focusing on basic functionality and drastically reducing the cost of air travel, thus allowing a whole new category of consumers to fly. As with any disruptive innovation, it was enabled by an “infrastructure” innovation, which in this instance was the combination of airline deregulation and of an aircraft product (twinjet narrowbody) perfectly fitted for short-haul trips.

Another example of disruptive innovation according to Christensen’s theory was the Joint Direct Attack Munition or JDAM—built by Boeing for the U.S. military—that became particularly successful in the late 1990s. The JDAM was essentially a“dumb” bomb made smarter with the addition of a set of maneuverable fins and a GPS guidance system. While initially designed to address low-value targets at short range, it became the weapon of choice for most air-to-ground missions in Afghanistan at a fraction of the cost of missiles such as the Tomahawk, the capabilities of which “overshot” the needs of the military for most missions.

A similar thing happened in Europe with the AASM guided bomb superseding missiles for most Rafale air-to-ground missions over the last 20 years. Like JDAM, the AASM turned out to be “good enough” for a large majority of military customers’ needs, thus disrupting traditional missile manufacturers.

In the space sector, Elon Musk obviously disrupted the launch sector but, interestingly, the disruptive part of it was not that he addressed a low-end segment with a less capable technology. In fact, from the beginning, Musk targeted the high-end segment of the market (expensive and large geosynchronous [GEO] government and commercial satellites) with a fairly traditional technology. What was truly disruptive about SpaceX initially was that Musk created his own ecosystem, designing his own rocket, vertically integrating its production and acquiring his own test range, which was something straight out of Christensen’s book.

As a new entrant, it is indeed extremely hard to disrupt an industry without creating a whole new ecosystem of your own, simply because there are too many vested interests in the existing one. In Christensen’s lingo, you are more likely to succeed as a disruptor with an “architectural” innovation than with a “component technology” innovation.

Another recent disruptive innovation in space has been the emergence of CubeSats. Not so long ago, the trend was for satellites to become ever bigger, more complex and more expensive. With CubeSat (shoebox-size) technology, the space industry finds itself on a radically different performance trajectory (see graph). As with most disruptive innovations, it started by addressing the needs of “low-end” customers (universities) with a very basic technology, but performance is continuously improving to the point where it is starting to compete with traditional satellites for Earth-observation and telecommunication missions.

So what will be the next disruptive aerospace innovations, according to Christensen’s theory? Most probably drones and unmanned aircraft for the military aircraft market, and possibly—further down the line—flying taxis or private flying vehicles for commercial aviation.

Indeed, a key characteristic of a disruptive innovation is that it enables unskilled people to do things that only experts could do before. This will clearly be the case if, one day, getting a pilot’s license for a flying car—autonomous or not—is as easy as getting a driver’s license today, or supersedes it altogether because our urban transportation systems will have become fully 3D. That will be a disruption, all right.

Antoine Gelain is managing director at Paragon European Partners, based in London.

The views expressed are not necessarily those of Aviation Week.

Comments