Rolls-Royce’s UltraFan next-generation turbofan is still without an application. Despite the uncertainty, the engine-maker is pressing on with assembly of the first demonstrator this year as a pivotal step toward building trust in the technology and preparing for production variants when the time is ripe.

“We need to get the engine ready for future opportunities and for whatever market dynamic evolves over the next 2-4 years,” says UltraFan Chief Engineer Andy Geer. The role of the demonstrator, which will be fully assembled by year-end, is to “get everybody’s confidence up so that when [a new potential application] does emerge—and it might emerge quickly with a desire for something different—-then we’re ready to go,” he says.

- Build underway for first demonstrator power gearbox

- Composite fan case and blades are undergoing completion

Although the engine-maker signaled in January that it will suspend further investment in the geared-engine concept beyond development of the 87,000-lb.-thrust demonstrator-—pending emerging opportunities—the scalable design remains vital to Rolls-Royce’s sustainable-product plan. But recognizing the realities of the effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the air transport market, Geer says: “The pace at which we move is a function of the pace the world needs us to move, as well as our own ambition.

“We’re still aiming for service entry around the turn of the decade, though goodness only knows what the market really wants—though that will settle,” Geer adds. The company, therefore, plans to stay on its original course to test the first of four platform-agnostic demonstrators starting in 2022. At the same time, learning lessons from the baseline engines, Rolls plans to remain agile and responsive to whatever market needs may emerge from Airbus, Boeing or even Embraer across the UltraFan’s intended 25,000-100,000-lb.-thrust range.

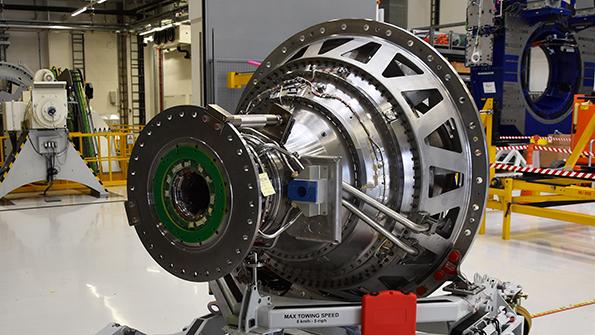

“Things are going to move quickly now, with parts arriving and getting into the build of modules. Then we’ll be assembling modules into the first full engine,” Geer says. The first power gearbox (PGB) at the heart of the new engine is now in assembly in Germany. Designated DP211 as a nod to the heritage of the company’s original RB.211 engine family, the gearbox is expected to be ready for shipment to Rolls-Royce’s Derby, England, facility for integration into the demonstrator around midyear.

Designed to slow the fan speed while allowing the intermediate turbine to run at higher optimum speed conditions, the final demonstrator configuration PGB ran to full power on a rig in Germany at the end of December. “We’ve now been up to full maximum takeoff power conditions, as will be required for the support of the demonstrator, which was a massive success for the team out there,” Geer says. “The gearbox is transforming well over 50 megawatts of power in a space about 1 m2 [10.7 ft.2] and runs to full thermal stabilization in takeoff condition for probably 10 min. at a time. It is meeting nominal performance targets, and thermal efficiency is better than 99%.”

The composite fan case for the initial demonstrator, UF001, is close to completion at Rolls’ Bristol, England, site, where accessory parts are being attached and final machining is taking place. “A test unit like this has a lot of instrumentation in it, so the flow times and manufacturing are more complicated for a development unit than they would be for a production one,” Geer says.

The initial set of 18 composite-titanium fan blades that will fit within the case’s 140-in. internal diameter are also “going through the same sort of process, where we attach parts such as the leading-edge metal work,” he says. “We are making an awful lot more of them because we’re running a whole series of rig test programs and component test programs that also demand blade input, so there are a lot of blades to manufacture.”

As part of its overall sustainability drive, Rolls also plans to have the UltraFan be the first large high-bypass turbofan to be designed for use with 100% drop-in sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) “out of the box,” Geer says. To this end, Rolls ran a series of ground tests in late 2020 with low-carbon SAF using a modified Trent 1000 incorporating the ALECSys (advanced low-emissions combustion system) lean-burn combustor, which will run in the new high-pressure UltraFan core. The unblended fuel used in the tests, from World Energy, holds the potential to reduce net CO2 life-cycle emissions by more than 75% compared to current jet fuel and has the potential for further reductions.

“What happens if you’re operating for a long duration on fuels that lack some of the additives or aromatic contents that have been typical of historical fuels?” Geer asks. “It’s in the detail of the fuel-control-delivery system where we’ve ensured we’re operating with polymer systems and other materials that don’t object to that lack of aromatics.”

Beyond this, Geer says the UltraFan design has the potential to take further system-level advantage of operating with SAFs and, ultimately, even hydrogen. “For SAFs particularly, there are some opportunities in terms of thermal stability, calorific content and lack of contaminants and additives. So those are things where potentially we have an opportunity in the future to take advantage of that particular brew to get positive benefit out of it.”

Further off, SAFs as well as hydrogen offer even more from a heat-sink perspective. “In some cases, they’re better at absorbing heat,” Geer says. “Although that’s beyond where we’ve got to today, we’re obviously starting to think about what that means. If you look at a productionization of the systems, rather than the technology enablement of them, there’s going to be some opportunity there.”

As parts for UF001 start to arrive at Rolls-Royce’s “DemoWorks” in Derby, the company has launched the first “build packs” of components for various subassemblies. It is also evaluating new assembly methods based on electronic instruction systems under which engineers and mechanics are practicing putting replica components together. “Part of the UltraFan demonstration is proving not just the technology but also some of the processes, so we are taking the opportunity to pilot different ways of working,” he says.

The replica parts, made from additively layered manufactured plastic, are derived from the same digital design set as the real engine. “These parts flow through to the production assembly sequence process, and here we can try out that sequence information. We can check that the supporting geometric information, alongside the actual parts and the tooling itself, all comes together to allow the team to build the engine effectively,” Geer says.