Airbus formalized some pretty significant changes to its senior leadership in mid-April: Dirk Hoke, the CEO of Airbus Defense and Space, confirmed his departure later this summer, as did Grazia Vittadini, the charismatic and popular chief technology officer. In addition, the influential chief operating officer (COO) position will soon be held by Alberto Gutierrez, while incumbent COO Michael Schoellhorn will replace Hoke. Two weeks later, CEO Guillaume Faury announced more changes, this time to the industrial setup, fostering deeper integration of aerostructures manufacturing.

- Airbus creates large aerostructures subsidiaries

- Detailed parts production will be spun off as non-core

On the surface, the staff moves and industrial reorganization may not appear to have much in common. But a theme is emerging more clearly of late, two years after Faury moved into the Airbus CEO role: Centralization and integration are being reinforced and will be managed by a team of executives particularly loyal to Faury. Hoke has long had ambitions to become CEO, hopes that were dashed when the board opted for Faury. Vittadini, who has also not been part of Faury’s inner circle, sometimes clashed with Jean-Brice Dumont, Airbus head of engineering and a close associate of Faury. The appointment of Gutierrez, who has so far not been in the top tier of Airbus executives, shows that politics and tactics continue to play a role behind the scenes.

The latest action concerns a part of Airbus’ complex industrial setup. Faury is proceeding with his plans to reintegrate a large part of the aerostructures work into the core Airbus business while also carving out a detailed parts company that could be sold later. The plans are subject to negotiations with unions, which were briefed in more detail on April 21, which means there could still be changes to the setup—though the decision itself is not in doubt.

Management concluded that most of what aerostructures subsidiaries Premium Aerotec and Stelia Aerospace do is so core to Airbus and its future that they should not be sold. Faury argues that Airbus’ move into the digital design, manufacturing and services (DDMS) strategy, which integrates the three phases digitally, makes it necessary to keep tight control over a broader part of the design and manufacturing process—even of larger components that Boeing is happy to source from suppliers, such as 737 fuselages produced by Spirit AeroSystems. DDMS is the basis upon which Airbus plans to develop all future generations of aircraft. And while Airbus is unlikely to launch any new programs before its planned move into the next generation of hydrogen-powered aircraft slated for entry into service by 2035, DDMS will be used to build derivative aircraft such as a possible A322 (a stretched, rewinged and reengined version of the A321neo) or a freighter version of the A350.

The move, to be implemented at the beginning of 2022, would reverse an earlier 2009 decision to set up two aerostructures companies in France and Germany, Aerolia and Premium Aerotec. Aerolia later merged with Sogerma, another subsidiary, and was renamed Stelia Aerospace. Under the previous management team led by former CEO Tom Enders, Airbus had hoped to sell both Aerolia and Premium Aerotec—much like Boeing sold Spirit AeroSystems. But the sales never happened, in part because demand dropped in the aftermath of the global financial crisis.

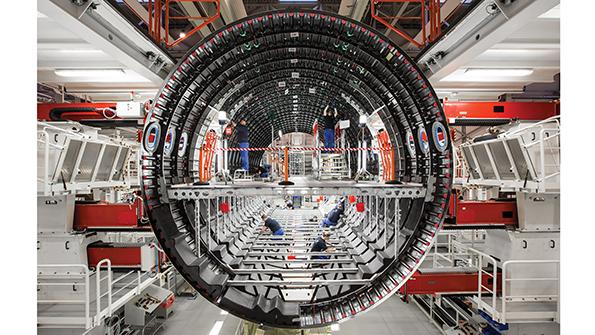

Premium Aerotec is based in Augsburg, Germany, and has additional factories in Varel and Nordenham. Stelia Aerospace mainly comprises aerostructures facilities in Meaulte and Saint-Nazaire in France. Both companies build subassemblies up to fuselage sections across the range of Airbus products and divisions.

The latest plans call for the creation of three new companies. One would be based in France and combine the current Stelia businesses with Airbus sites in Saint-Nazaire and Nantes, France. That entity would produce, among other things, the nose fuselage and center wingboxes for all Airbus programs, the forward fuselage of the A320 and the central fuselage of the A330 and A350. It would have 12,000 employees at 16 sites.

Another new company is to be created in Germany. It would bring together all German Premium Aerotec facilities—except Augsburg’s Plant 4 and the company’s facilities in Varel—with Airbus’ site in Stade and its structural assembly in Hamburg. The new enterprise would build the forward fuselage of the A330 and A350, the center fuselage of the A320 as well as the rear fuselage and tail cone for all programs. The company is planned to employ 7,000 people in five locations.

These two firms would no longer be considered suppliers to Airbus but instead would be integrated into the Airbus production system and flow. That said, they would remain distinct, separate entities.

The third company would be focused on detailed parts and have an estimated €900 million ($1.1 billion) in annual sales. It would combine the Premium Aerotec sites in Varel with Plant 4 in Augsburg and a facility in Brasov, Romania. Airbus says it is “reviewing different ownership structures to identify the best possible solution” for the parts business. The company believes it can create a strong global player in the detailed parts industry that would be sustainable and competitive with “an appropriate investment strategy.” The newly formed venture could count on a “long-term growth perspective” with Airbus as major customer, the OEM says, but also may work with external clients on civil and defense products.

The company would produce machined, milled and turned parts and have capabilities in metallic and nonmetal components.

The changes identify Airbus’ red line as to what work it is prepared to leave to suppliers and indicate that detailed parts production is not something the manufacturer considers vital in-house work. What they do not address is whether the company’s complex industrial footprint needs a revamp. While no changes are expected—or even possible—in the short term, questions loom on the horizon. The role of Airbus’ plant in Bremen, Germany, has been debated internally for some time, but Faury has not addressed it yet. Airbus also needs to attend to the post-Brexit future of its UK sites at some point, though major changes are only likely when workshares of new aircraft programs need to be decided.

More important than the unlikely prospect of rationalizing its industrial presence across Europe is a side effect of the reshuffling: the strengthening of Airbus’ in-house aerostructures capabilities. Airbus could take on more work itself, and that is a threat for suppliers. According to industry sources, the message from Airbus has already been received by some suppliers that may be directly affected in the not-too-distant future and others that are starting to worry about what the moves could mean for them further down the road.

Two companies that probably have more reason for concern than others are Spirit AeroSystems and Leonardo. Spirit is building the composite center fuselage section of the A350 and the A220 wings, among other things. Leonardo is building the horizontal and vertical stabilizer for the A220. Airbus was about to start renegotiating terms with the A220 suppliers when the novel coronavirus pandemic hit and suppressed production rates. Airbus aimed at significantly better conditions than the A220’s previous owner, Bombardier Aerospace, could reach. Similarly, the A350 is still facing cost pressure, which has only become worse as rates fell to less than five aircraft per month from 10.

According to the industry sources, Airbus has made clear it expects new agreements with its key suppliers in both programs—not just the A220. At the same time, the company has invested massively in new production technology at Augsburg and Nordenham for the A350, infrastructure that is now underutilized.

In the near term, Airbus’ site in Cadiz, Spain, is in focus and that is where the Gutierrez appointment comes into play. The restructuring plan for the Puerto Real plant in Cadiz has been hit hard by the termination of the A380 program and the slowdown of other widebody programs, threatening around 300 jobs there. Airbus “continues to work with the social partners to identify solutions that will optimize the industrial setup,” the company says. Given that Spain has always felt overshadowed in its Airbus role by the much bigger French and German presences, any move is certain to face massive political backlash, even though Cadiz is such a small site.

The topic of facing backlash is something Faury has to keep in mind. Making Airbus a bigger, more centralized entity that covers more of the supply chain also increases risk when things go wrong. For the company, it means tight control over processes is needed. For Faury, who now has upped the game personally, it means he needs to deliver.

Comments