Higher And Faster: The Quest For Speed

November 24, 2015

The National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) was a very different beast from the big-money, bureaucratic, politicized jobs machine that its successor, NASA, turned into within a decade of its establishment. The old NACA was first through Mach 1, Mach 2 and Mach 3, and its final triumph was the North American Aviation X-15, deliberately designed as a bridge between the airplane and a reusable spacecraft.

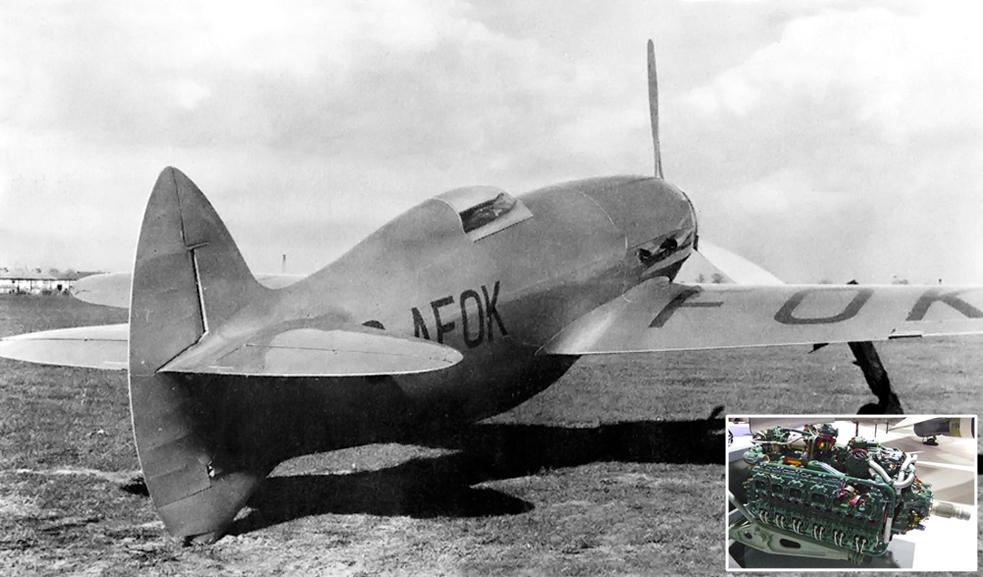

Mayday or SOS? One way to win the coveted Schneider Trophy, Piaggio designer Giovanni Pegna reasoned, was to ditch the big pontoons, which were nothing but drag, wetted area and a place to put radiators once the airplane took off. The P.7, built for the 1929 race, floated deep in the water, its flight propeller stopped covered, with a water propeller and hydrofoils to lift it out of the water. Clutches were then supposed to shift power to the flight propeller. It never flew.

With its economy in the depths of the Great Depression, Britain’s Labour government understandably decided not to fund a Schneider Trophy team in 1931. Lady Houston, a staunch right-winger who had been a teenage chorus girl in the 1870s and inherited millions from her third husband, gave £100,000 (about $9 million today) to fund a winning team flying the Supermarine S.6B, an upgraded version of the 1929 racer. It set the first world airspeed record above 400 mph.

The fastest Schneider Trophy racer, the Macchi-Castoldi MC.72, wasn’t ready for the 1931 contest, but Mussolini’s government continued in quest of the airspeed record. Its Fiat AS.6 engine comprised two V-12s mounted nose-to-nose, each driving one of a pair of contrarotating propellers—eliminating torque effects that caused Schneider racers to bury one float on takeoff—and supercharged by a single blower driven by the aft engine. Backfires in the long induction system caused at least one inflight explosion and probably caused another, killing two pilots.

Proving themselves as speed-crazed as the Italians, a British team financed by car magnate Lord Nuffield flew the Heston J.5— solely designed to break a speed record—in June 1940, when one might have thought they had other things to worry about. It crashed on its first flight, fortunately without killing its pilot. The J.5 was designed around the phenomenal Napier Sabre engine, a sleeve-valve H-24 that would eventually develop 3,000 hp in service and give the hulking Hawker Tempest a 50-mph speed advantage, at low altitude, over any other piston-engine fighter of World War II.

In May 1943, Britain’s Royal Aircraft Establishment started a series of high-speed dive trials at Farnborough using a Supermarine Spitfire PR.XI, chosen because of its speed and altitude performance. Monitored by one of the first Machmeters, the dives started at 40,000 ft. and reached more than 600 mph around 28,000 ft. The final trial reached Mach 0.92, at which point the propeller decided that it had taken enough abuse and left the Spitfire and pilot to their own devices. The Farnborough data was shared with NACA and helped guide development of the Bell X-1.

Group Capt. E.M. Donaldson sets the second jet world airspeed record at 616 mph in a Gloster Meteor F.4 in September 1946. “Teddy” Donaldson became air correspondent for the Daily Telegraph after his retirement from the Royal Air Force, thereby becoming the only aviation journalist to hold the speed record.

At least it looked fast. Designed under a 1945 NACA contract, the Douglas X-3 was aimed at sustained speeds above Mach 2. Its intended engine, the afterburning Westinghouse J46, was unsatisfactory, and it had to fly with the smaller J34, which could not propel it above Mach 1 in level flight. However, its 260-mph takeoff speed remains unchallenged.

Bell’s X-2 rocket-powered research aircraft had a long and hazardous development. The project was launched in 1945, but difficulties with the rocket engine and other technologies delayed tests until the early 1950s. One of the two aircraft exploded during a captive-carry test, killing the pilot and an engineer aboard the Boeing B-50 mothership. In 1956, the surviving X-2 reached 126,000 ft. on its 12th powered flight and became the first airplane to exceed Mach 3 on the following flight—which ended in a fatal accident.

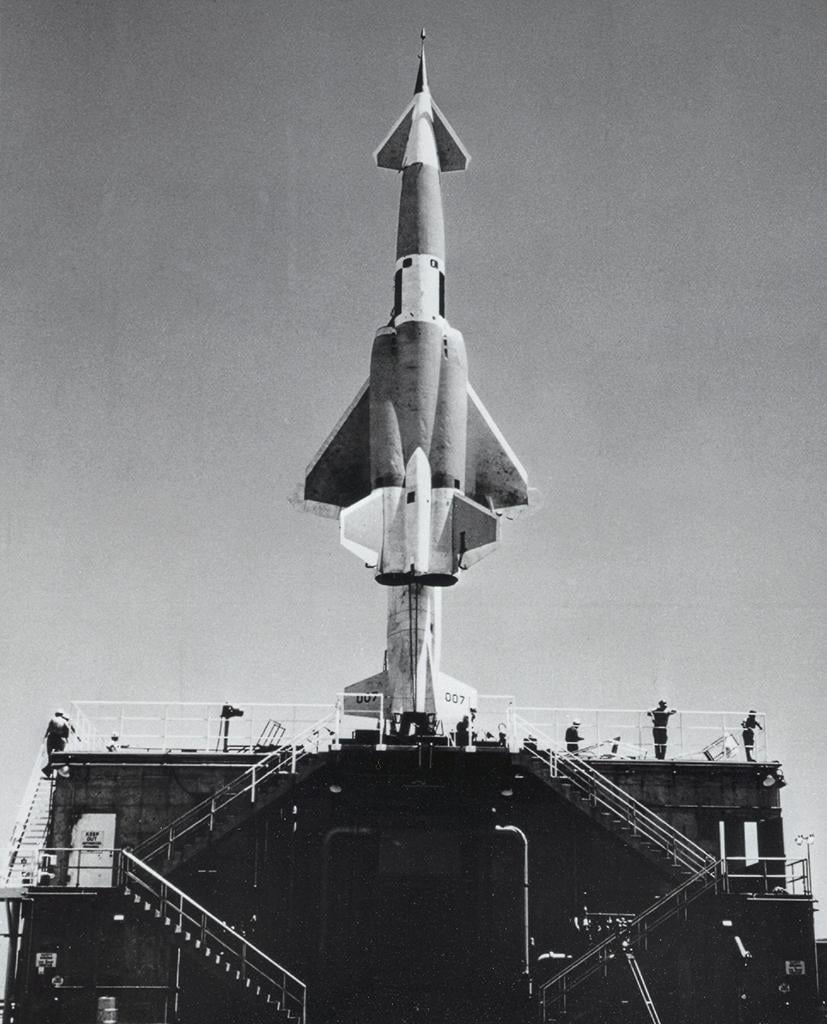

The North American XSM-64 Navaho project was aimed at creating a Mach 3 intercontinental cruise missile. It was to be launched vertically by a liquid-rocket booster, be powered by Curtiss-Wright ramjet engines and guided to its target with an astro-inertial navigation system. Ten near-full-size G-26 prototypes were launched from Cape Canaveral in 1956-57, but the project was canceled as soon as fundamental problems with intercontinental ballistic missiles were solved. The first operational U.S. ICBM, the Atlas, used the motors from the Navaho booster.

Britain flew an experimental rocket-plus-jet fighter, the Saunders-Roe SR.53, in 1957 as a potential defense against supersonic bombers. The de Havilland Spectre rocket, running on kerosene and hydrogen peroxide, was the primary engine—the small turbojet provided electrical and hydraulic power and powered the airplane on its return to base. One advantage of the rocket was that it provided more power as altitude increased, the opposite of a jet engine. The larger and more capable SR.177 was canceled after the 1957 Defense White Paper concluded that there would be no manned fighters after the British Aircraft Corp. Lightning.

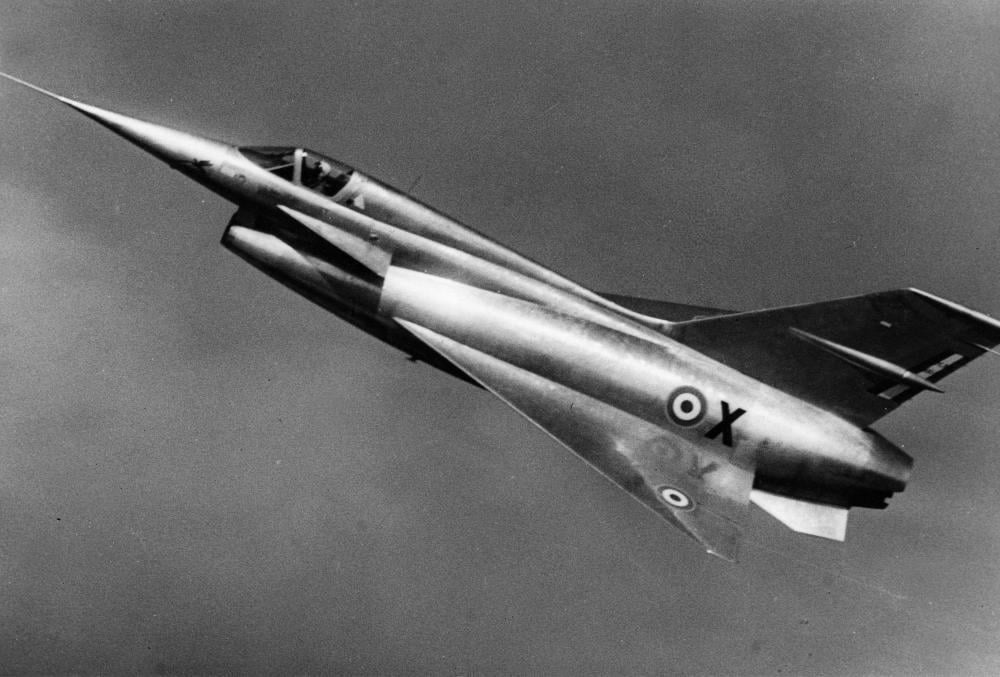

Aiming at similar requirements to the SR.53, in the late 1950s, France flew a rocket-plus-jet interceptor but also pursued ramjet developments, including the Nord Griffon experimental fighter with a combined turbo-ramjet propulsion system. It was not proceeded with, because the more conventional Mirage III (with a 3,400-lb.-thrust booster rocket) showed more promise, but French ramjet technology continued, leading to today’s ASMP-A supersonic nuclear cruise missile.

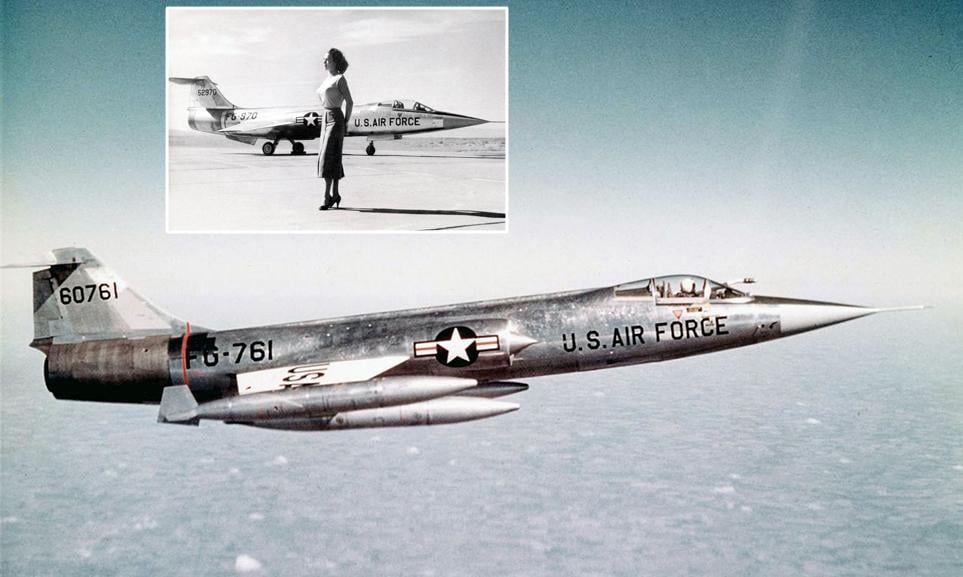

Speaking of the Mirage: The half-cone inlets of the Lockheed F-104A Starfighter were considered highly secret when its existence was revealed in early 1956, but by the time they were disclosed, Dassault was well along with similar inlets for the Mirage, which flew with the so-called souris (mice) in July 1957. In the meantime, some F-104As were shown with metal covers over the inlets, while other measures (inset) were taken to conceal them in PR photos.

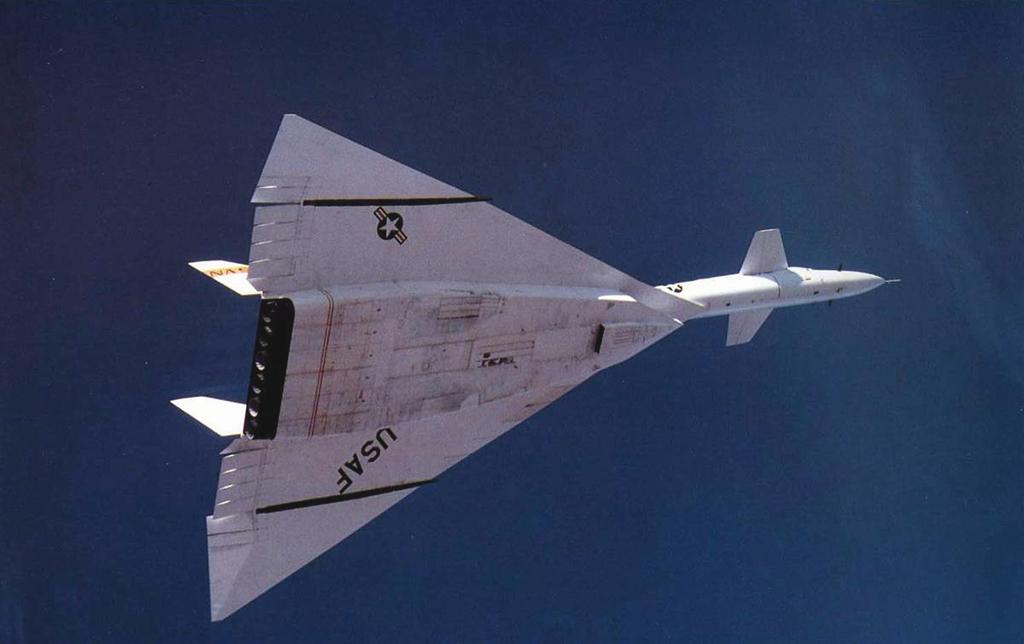

At one point in its development, the North American XB-70 Valkyrie bomber was expected to be both the fastest and heaviest aircraft in the world, but it was secretly eclipsed in speed by the Lockheed A-12. Plans to use boron-slurry high-energy fuel had to be abandoned, and the stainless-steel honeycomb structure was a nightmare. The first airplane was limited in performance by structural problems and the second was lost in a midair collision before exploring its full envelope.

Designed to intercept the A-12, the MiG-25 Foxbat was designed around two very large, simple, low-pressure-ratio Tumansky R-15-300 turbojet engines that could be run at full throttle at high Mach numbers without exceeding the limits of known materials. The designers invented an entire system of welded steel construction for the airframe. The later MiG-31 derivative is the fastest known military aircraft today.

McDonnell Aircraft designed the Model 192 Isinglass boost-glide vehicle for the Central Intelligence Agency in the 1960s. The project remains largely classified, but the 132,000-lb. vehicle was intended to be carried under the wing of a B-52, with a liquid hydrogen fuel tank on the opposite side and a liquid oxygen tank in the B-52 bomb bay, and to be fueled immediately before launch. The Pratt & Whitney XLR-129 engine was built and ground tested, and specimens of the roll-bonded titanium structure were produced, before the project was canceled in 1968.

In 1984, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency launched the Copper Canyon program to investigate an advanced compound-cycle hydrogen-fueled engine invented by Tony DuPont. Air flowed into a heat exchanger, cooling and densifying the air and heating and expanding the hydrogen through a turbine, driving a compressor. The air and hydrogen were mixed and injected into a ramjet duct, inducing more airflow and allowing it to produce power at zero airspeed. Copper Canyon was the start of the National Aerospace Plane (NASP) project, but that vehicle reached a projected weight well above 400,000 lb.—eightfold more than an early estimate—before it was canceled.

One theory about NASP—voiced openly by a senior European space official in 1992—was that it was a cover for a secret hypersonic or high-supersonic project, the subject of extensive rumors and reports and publicly nicknamed Aurora. Unexplained sonic booms over southern California in 1991 and the 1989 sighting of an unidentifiable delta-shaped craft over the North Sea bolstered the hypothesis, along with the expansion of the secret base at Area 51.

Trying to design, build and fly the world’s fastest airplane is a challenge that has brought out the genius in aerospace engineers and has occasionally tapped a vein of risk-taking eccentricity. This selection of some of the triumphs, disasters and mysteries in the pursuit of speed as part of a series of special Centennial editions to mark the 100th anniversary of Aviation Week & Space Technology.

Read more about the quest for speed (subscribers):