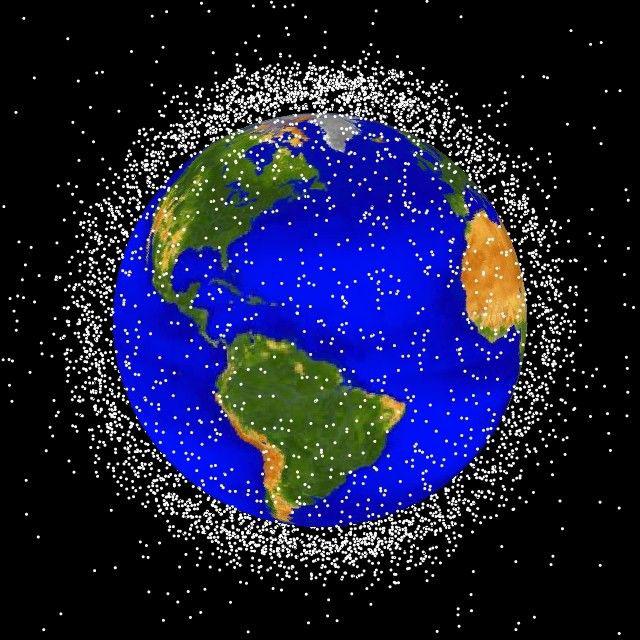

HOUSTON—An estimated 5,000 spent rocket bodies and retired multinational spacecraft that circle the Earth—some with a mass of up to several tons—are part of a growing orbital debris population that poses a lingering collision threat to national security and civil space assets.

Among those assets are the International Space Station and the connectivity provided by commercial communications satellites.

The challenges to active removal include cost and international cooperation, according to a pair of experts who joined the Brookings Institution May 13 for a webinar on the topic, “Space junk—Addressing the orbital debris challenge.”

“For meaningful remediation we may need to remove most of them from the space environment,” Jer Chyi Liou, NASA’s chief scientist for orbital debris, said of the large objects. “It’s really cost prohibitive based on today’s economics. Many groups have proposed a concept on how to remove debris. However, until a very low-cost solution is identified, environmental remediation is not realistic.”

But even a promising cost-effective strategy raises a concern that the technology could also become a disguise by an adversary to destroy the orbital assets of another.

“Having policies that actually spell out how you do close rendezvous and proximity operations in a way that does not threaten others is really important,” said Victoria Samson, director of the Washington office of the Secure World Foundation.

Samson urged bilateral discussions as well as exchanges through the United Nations and its Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space as helpful venues. She also mentioned the DARPA-funded Consortium for Execution of Rendezvous and Servicing Operations.

“The space domain is really changing and evolving,” Samson said. “We are just figuring out the rules as we go along, and sometimes activities in orbit get ahead of some of the issues.”

Though it was not mentioned during the webinar, massive spent rocket bodies can pose an impact threat to populated regions of Earth as well as being a collision threat to valuable satellites.

On May 11, the core stage from a Chinese Long March 5B rocket—launched six days earlier with a test version of a future human spacecraft—made an uncontrolled re-entry into the Earth’s atmosphere. It was possibly responsible for the debris that landed on the Ivory Coast of Western Africa, according to a Twitter account of the incident provided by astronomer Jonathan McDowell of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.

Another bottom-line issue, said Liou and Samson, is who pays for the removal of the largest pieces of orbital debris and who is liable for damages?

China has increased its activities in space, a domain not owned by any one nation, on both the military and civilian fronts. If those activities are viewed as potential national security and economic threats, they also represent significant investments by the Chinese, Samson said. As such, China should have as much interest as the U.S. or Russia in acting responsibly.

Liou also stressed an equal need to address a surge in the small debris environment in low Earth orbit. It now consists of 23,000 objects 10 cm and larger, 500,000 objects 1 cm and larger, and 100 million objects 1 mm and larger. All are moving at velocities 10 times that of a bullet fired from a gun, enough for even the smallest to rupture a fuel tank, battery or another critical component on any of the 2,200 operational spacecraft now circling the Earth, he said.

Both presenters noted concern is on the rise as large constellations of small communications satellites like Elon Musk’s Starlink are launched. If the business case for a new small satellite venture fails to close—Samson mentioned OneWeb—who inherits responsibility for damage?

Each emphasized the need for regulatory bodies to reach agreement on an end-of-life orbital time constraint and the need to assure that the design, development and assembly of the small sats are of high reliability.

Each collision creates debris that then carries the threat of generating even more debris, Liou stressed. The concept known as the Kessler Syndrome was demonstrated as the result of a 2007 Chinese anti-satellite test and the collision between the retired Cosmos 2251 military satellite and the operational Iridium 33 communications satellite in 2009.

“There is no one silver bullet on how we fix the orbital debris problem. We will have to have a variety of approaches, mediation and mitigation. Both are incredibly important,” Samson said. “We need to recognize that the space domain is evolved over the past several years, and our governance needs to evolve with it.”