An Exclusive Look At Sbirs And Its Capabilities

October 16, 2015

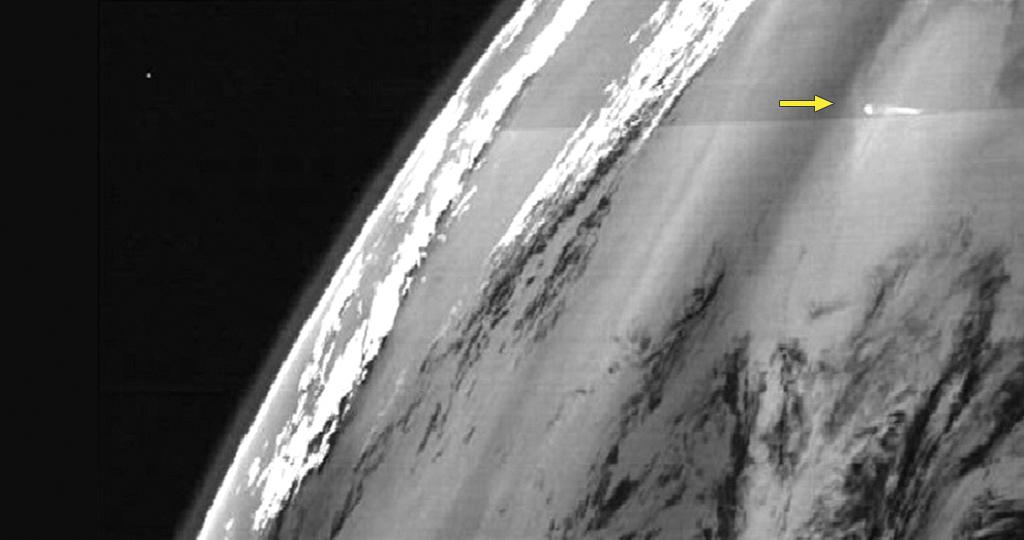

Though unwilling to provide details or unvarnished imagery from the new Sbirs sensors in orbit, many an Air Force general officer has described the new products as “eye-watering.” This is the first and only image released for public use from the Sbirs system. It was provided exclusively to Aviation Week for publication Nov. 20, 2006, shortly after the first sensor in highly elliptical orbit began service. It captures the heat plume emitted by a Delta IV rocket as it climbed Nov. 4, 2006, from Vandenberg AFB, California, carrying a Defense Meteorological Satellite Program spacecraft to an insertion point en route to polar orbit. The plume is readily visible (noted by yellow arrow in upper right side of photo) as it travels against the backdrop of Earth.

The launch took place at an ideal time for the sensor, which was then new and being calibrated. In the morning hours when this launch took place, the hot rocket plume shows brightly against a cool Earth, which had not yet been touched by morning sunlight and heat. This image was degraded for use by the U.S. Air Force to obscure the sensor’s true capabilities.

The first Sbirs sensor to go operational was HEO-1, named to reflect its mission operating in highly elliptical orbit on a classified host satellite. It was launched June 27, 2006. HEO-2 and -3 have also been lofted. Pictured is a 530-lb. HEO payload that dwarfs the humans inspecting it.

From their vantage in HEO, these sensors—designed to scan the entire field of view in a “racetrack” pattern in less than 10 sec. (the actual revisit rate is classified)—can loiter over the upper tiers of Earth. This orbit is especially useful to see ICBM launches over the North Pole that could come from Russia or North Korea. The Sbirs scanning sensor can image objects using its short-wave and mid-wave infrared detectors. It also has a “see-to-the-ground capability” about which the Air Force has said little.

However, Jeff Smith, a Lockheed Martin executive, said in 2011 prior to the first Sbirs GEO launch that it uses a “wider, more open short-wave” band. “It is opened up more, which means more clutter and more targets at the same time. That is why you can see deeper into the atmosphere,” he said.

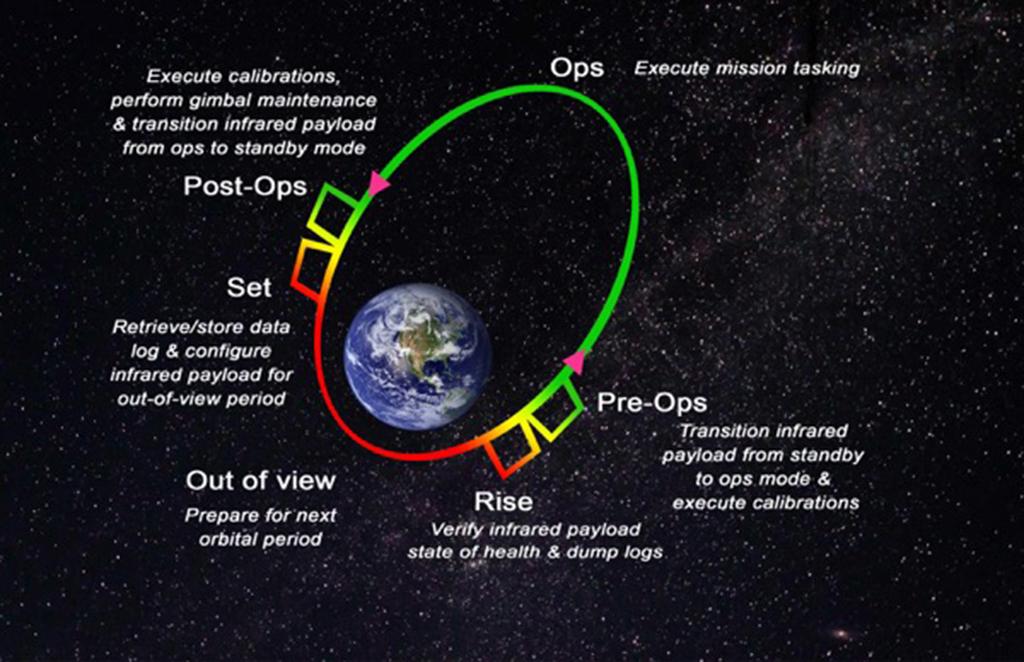

HEO orbit allows Sbirs to dwell over the northern tier of the Earth scanning for launches. This is most useful for detecting potential launches from Russia or North Korea, which would travel over the pole to targets in the U.S. or its territories. HEO orbit provides a view of the North Pole and overlaps some areas already covered by DSP and Sbirs satellites in GEO orbit. The egg-shaped HEO orbit allows for roughly 70% of each orbit to support operations, as depicted by the green line. Once a pass is complete, operators retrieve and store the data collected during the previous revolution. They then prep the satellite for its next pass. Three HEO sensors are in orbit today.

The ambitious Sbirs GEO satellite design came to life after years of technical hurdles and cost overruns. A sun shade was added to the design after engineers realized the scanning and staring sensor faces would be exposed to too much heat and glint from the Sun. Later, electromagnetic interference problems befuddled designers and delayed the program for years, an issue of special concern for the HEO payloads, as they could not perturb the mission of the classified host satellite’s primary sensor. In addition, a computer processing timing issue for years held up the first GEO launch, which finally occurred in 2011.

A classified Lockheed Martin satellite that went dark 7 sec. after reaching orbit in 2007 used similar software, and the safe-hold mode (used for basic health and communication in the event of an on-orbit fault) failed. At the time, Gary Payton, then-Air Force deputy undersecretary for space, dubbed that spacecraft a useless “ice cube.” This forced engineers to conduct a major redesign of the flight software for Sbirs to avoid the same problem before the Air Force would sign off on a launch.

Managed under a “total system performance responsibility" contract, a type popular in the late 1900s, Air Force officials now admit that handing over so much design and systems engineering oversight to the contractor was a major mistake. Originally estimated to cost $5.2 billion (for five satellites), the system is now expected to cost $18.9 billion for six of them. GEO-1 was launched nine years later than planned.

The Sbirs GEO design incorporates side-by-side sensors, both provided by Northrop Grumman (formerly TRW). The scanning sensor is virtually the same as the one flying on HEO sensors. The staring sensor, however, is newer technology. The green in this image represents the scanning sensor’s footprint, while the blue swath represents the starer’s capabilities. The starer can provide continuous watch over an area or be quickly retasked or programmed to glimpse at a number of areas.

“The staring sensor has enormous flexibility in terms of refresh rate, sensitivity and agility, and it is proving to be especially useful for battlespace awareness,” Guetlein says. Program officials are now developing new processing algorithms to better exploit staring-sensor data “in ways never envisioned by Sbirs designers in 1996.” Officials tout that the starer can see “dimmer” targets, meaning those that burn at a lower temperature or for shorter duration than strategic missiles. These include cruise missiles, unmanned aircraft, mortars, rockets and artillery, among others.

Sbirs is also increasingly being used to support nonmilitary operations. Examples include providing data to unravel the sequence of events when a Russian-made BUK, or SA-11, missile shot down Malaysia Airlines Flight 17, killing 283 passengers and 15 crew on July 17, 2014. Though the Air Force is mum on the specific contribution from Sbirs, the system is designed to track missiles in flight and provide data to characterize their type model.

“This is the art of what we do,” says Col. Mike Jackson, 460th operations group commander at Buckley. Officials at the 460th Space Wing also confirmed Sbirs provided technical data to the intelligence community to help solve the mystery of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370 (MH370), which disappeared over the Indian Ocean in March 2014.

From DSP to the Sbirs scanner to the Sbirs starer, each evolution has provided more precision in the infrared returns used by operators. Among the key improvements offered by the three is far more precision in the state vector—or burnout velocity and direction of missiles. A more accurate state vector allows for more precision in cueing other missile defense assets, such as radars. It also shortens the time needed for these other sensors to acquire the target and, eventually, engage it.

Engineers intentionally designed the Sbirs operator’s work console to be as simple as possible so as not to distract operators with needless details, such as intricate map features. In this representation of a potential launch from North Korea, you can see what an operator would see. The green shapes represent raw infrared returns on the launch, each from a different sensor. The missile’s acceleration is evident as these symbols get farther apart though the system is imaging at the same rate. Within seconds, operators must confirm a launch and relay data to U.S. Strategic Command, which will react with defenses, if needed. Generating a certified Integrated Tactical Warning Attack Assessment message—the highly controlled format used for reacting to a launch—requires that two officials verify the threat.

While this view depicts one launch, operators are being trained now to handle “raid” attacks. More and more, would-be adversaries are testing salvo launches in attempts to overwhelm U.S. sensors and interceptor magazines. Jackson says operators tracked 32 launches during a single “ripple launch” event that took place within the last two years.

Ironically, the average age of a Sbirs operator is about 20 years; most operators were not even born when the Cold War that generated Sbirs requirements ended.

This is an example of the 80-ft.-tall, ground-based antenna dish used to collect the infrared data from IR satellites in orbit. Housed in a 100-ft. radome that looks from the outside like a massive golf ball, the dish has been in operation since 1973. Two dishes are at Buckely to ensure that at least one is always receiving data.

Prior to launch, GEO-1 was encapsulated at Lockheed Martin’s facility in Sunnyvale, California. The satellite weighs about 10,000 lb. before it is launched. It is housed on the company’s A2100 bus, and the solar arrays are folded at the sides of the satellite for encapsulation.

Two HEO satellites are in orbit today. GEO-3 is in storage after completing the build process in Sunnyvale. HEO-4, still in production, will be the next to launch in 2017. HEO-3 is slated for liftoff in 2017. Lockheed Martin is in the early phases of building HEO-5 and -6, which incorporate a new design for the A2100. It decouples the once integrated payload and propulsion modules. The redesign was done to allow for quicker technology refreshes to the payload should the Air Force opt to buy more satellites.

Sbirs GEO satellites are transported to Cape Canaveral AFS from the production site at Sunnyvale via a cocoon container specially sized for the Air Force’s C-5, the Pentagon’s largest airlifter.

Sbirs GEO-2 captured this image, which was declassified and released exclusively to Aviation Week. It shows thunderstorms forming over the central United States in May 2013. Though the Air Force declined to release a Sbirs image of a missile in flight, this image hints at the sensitivity of the infrared detector and shows how the system can be used in roles unrelated to missile warning. The image was degraded for security purposes.

The U.S. Air Force set about its ambitious project, the Space-Based Infrared System (Sbirs), in 1996 with a goal of dramatically improving the products provided by overhead, persistent infrared satellites. These satellites are the first line of defense in the event of a missile attack against the U.S. or deployed U.S. forces, as they are the first to detect a launch. They are used to cue radars and interceptors.

Nearly 20 years later, Air Force officials say they are finally beginning to realize that plan. But it came at a high cost. The system is estimated to cost more than triple its original estimate, the first satellite was deployed nine years late, and many a bright, fast-burning colonel was “eaten alive” by foiled attempts to right the wayward program in the 2000s.

Now, operators at the 460th Space Wing at Buckley AFB, Colorado, are planning to implement a major upgrade and consolidation to the ground control architecture there. It is projected to usher in new capabilities far beyond the missile warning and defense roles. After years of unsuccessful requests to see Sbirs in action, the Air Force granted Aviation Week exclusive access to the new operations floor before control functions begin in earnest and classification rules restrict personnel there. Read more about Sbirs: Bringing the Heat