Opinion: Why GPS Is Lagging The Competition And What To Do About It

While overly focused on killing Ligado Networks’ proposed ground-based 5G network, the Defense Department has lost sight of and failed to deliver on its most important priorities for GPS. First and foremost, the department must provide a cybersecure, jam-resistant military satellite navigation capability to the armed forces. Second, the Pentagon has allowed the civil/commercial GPS capabilities it offers to fall behind those of its competitors. Though Congress has at times attempted to hold the Defense Department and the positioning, navigation and timing community accountable, stakeholders “overseeing” GPS management have resisted, fending off real scrutiny and the positive disruption and innovation that leads to resilience and continued technological dominance.

- The Pentagon developed GPS, but now it lags foreign competitors

- Development of military and civil GPS systems needs to be separated

- Fixing the problems will require a new division of responsibilities

The tragedy is that for the last 10 years, the Pentagon GPS community has focused its energy and countless dollars fighting a supposed threat from Ligado’s proposed use of L-band mobile satellite service spectrum that poses no appreciable harm to military or civil/commercial GPS capabilities. This wasteful drain of resources and deflection of management of the real problem has undermined the vitality, resilience and continuing global superiority of America’s GPS system.

In the “Beginning” (e.g., 1995)

The Defense Department was put on notice regarding military GPS’s cybersecurity and anti-jamming shortfalls almost 25 years ago. The Defense Science Board (DSB) Task Force on the Global Positioning System provided its report to then-Defense Secretary William Perry in November 1995. The DSB’s primary finding was that military GPS had inadequate resistance to current and evolving electronic warfare threats. In light of this report, at a congressional hearing on March 29, 1996, then-Vice President Al Gore announced a plan to modernize military GPS. In the summer of 1997, the Defense Department initiated development of a new military satellite signal called M-Code, as well as ground control system upgrades to manage the new military signals and upgraded cybersecure, high-antijam military GPS user equipment. In the 23 years since its kickoff, this critical effort to address real warfighting needs has proceeded at a glacial pace, increasing risk to the military and capabilities that depend on GPS resiliency.

M-Code Receiver Mismanagement

In 2011, five years after the Defense Department projected M-Code receiver development was to be completed, Congress grew worried about the Pentagon’s inability to successfully execute the program. It passed Public Law 111-383, Section 913 that prohibited the Defense Department from purchasing GPS receivers that did not use M-Code (with limited exceptions) after fiscal 2017. Moreover, in 2015, eighteen years after program kickoff, there were additional cost overruns and schedule slips on not just the M-Code Receiver Program, but also on the modernized GPS Satellites and Ground Control Network. Congress put the Defense Department on notice again. It passed Public Law 114-92, Section 1621, requiring the Defense Department to submit detailed quarterly reports to the Government Accountability Office (GAO) on the program progress for the GPS space, control and user segments until each segment was operational. And in 2018, a year after the Pentagon missed the M-Code receiver deadline in Public Law 111-383, Section 913, Congress passed Public Law 115-232, Section 1610. It directed the defense secretary to place someone in charge of the overall M-Code Receiver Card program oversight, with explicit yet very basic program management duties written into the law.

The Pentagon was also directed to provide an annual report to the relevant congressional subcommittees on M-Code modernization. The first report, like M-code itself, is a year late.

As indicated in the fiscal 2020 president’s budget request, the Pentagon is currently planning to spend more than $1.8 billion to procure, integrate and test the modernized GPS receivers in user platforms across the military services through 2024. The $1.8 billion figure will grow to $3.5 billion when the approximately one million military GPS receivers are transitioned to GPS M-Code military receivers. This transition will occur in 2035, at the earliest. So far, the one million M-Code chips that will go into these receivers have not been made by the the Pentagon’s trusted foundry.

Army Marching Into Battle With or Without GPS

The Army has grown suspicious of the Air Force’s management of the GPS program and tired of the continual delays. On October 14, 2019, as reported by Space News, Gen. John Murray, commander of Army Futures Command, told reporters at the Association of the U.S. Army annual conference: “What we are trying to do is develop alternative ways to get PNT [positioning, navigation and timing] other than GPS. We have to have multiple ways of getting PNT in the future battlefield because of the threat of jamming.”

In addition to the Army, Congress itself has grown weary of the continuous delays and unaddressed vulnerability of GPS. Rather than waiting until 2035, the Senate Armed Services Committee finally directed the Pentagon to provide alternatives to GPS PNT by 2023 in its version of Section 1601 of the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA). Funding for these alternatives will likely come at the expense of the GPS Space, Ground Control and User Equipment programs, which are already significantly over budget.

The Pentagon has known about this significant military GPS shortfall for a quarter-century and yet it is going to take another 15 years, at a minimum, to make the fix. During this prolonged period, thousands of soldiers, sailors, airmen and Marines will have been at risk. How can anyone rationalize that it took 40 years—from identifying the problem to actually solving it—without questioning the legacy power structures behind this mismanagement?

New Signal Delays

As of June 30, 2020, 24 satellites on orbit had the new military signal called M-Code. Nominally at least 24 satellites are required to declare an operational capability. Upgrades to the control segment are finally in place to manage the new M-Code military signals. However, no operational military receivers that can use the new military signals have been fielded. Today, eight of the 24 M-Code satellites have been on orbit between 11 and 15 years, well beyond their 7.5-year design life. It is quite likely that M-Code satellites on orbit today will fail or be retired before they are ever used to support actual military operations.

In its December 12, 2017, report, GAO expressed numerous concerns regarding schedule integration across the various parts of GPS to include its user base. In 2018, Congress schooled the Pentagon on how to manage the program in PL 115-232, Section 1610. How is it possible for such an important program to become so internally disconnected for so long with no effective action taken by the Pentagon to fix it?

Ground Control System Gone Out of Control

The new GPS ground control system is named “OCX.” Air Force Space Command Commander Gen. John Hyten called it “a disaster” at an Air Force Association (AFA) Mitchell Institute event on Capitol Hill, according to a Dec. 9, 2015, Air Force Magazine article. The program suffered a Nunn-McCurdy breach in mid-2016. (A Nunn-McCurdy breach requires congressional notification if the unit cost of a program goes more than 25% beyond what was originally estimated. It also calls for the termination of programs if total cost growth is greater than 50%, unless the defense secretary submits a detailed explanation to Congress.) In May 2019, the GAO reported OCX would probably be seven years late instead of five years. The GAO also recommended that the Pentagon conduct another independent schedule audit, which the Pentagon rejected. With the nearly continual cost overruns and schedule slips, why would the Pentagon NOT want to conduct another schedule assessment?

Satellite Sadness

The Defense Department’s management of the new GPS III satellite has not gone well, either. The first contract was awarded on May 15, 2008, for eight satellites at a contract value of $1.4 billion. The first launch was originally planned for 2014. At a February 7, 2014, breakfast in Washington sponsored by the Air Force Association’s Mitchell Institute, Air Force Space Command Commander Gen. William Shelton announced another slip to the date when the prime contractor is expected to have the first GPS III satellite ready for launch. “We’re not happy at all...Is my patience wearing thin? Yes . . . . Both the prime and the sub know exactly where we stand on this. I don’t think there is any shortage of attention. I don’t think they are wondering what we are thinking,” he said. The “ready-to-launch date” is not the same as the actual launch date, he added. That would have been at the end of fiscal 2015, he said. “I think we are going to slip well past that now,” he said, but made no prediction as to when that would be. In the end, the first GPS III satellite was not declared “ready-to-launch” until September 2017.

Eventually the first GPS III spacecraft was launched on Dec. 23, 2018—10 years after the contract award. That is the longest time from contract award to first launch in the history of the program. Costs have also ballooned over time. The Pentagon awarded a $7.2 billion contract for 22 more GPS III satellites on September 28, 2018, at a unit price of $327 million each. If you inflate cost per satellite paid for satellites purchased in 2008, that equates to $204 million in 2018. In 1981, the Defense Department paid $1.17 billion for 28 GPS Block II satellites—the equivalent of $115 million in 2018.

What does GPS III bring to the table? It depends on how you look at it. Civil and commercial users get L1C. The U.S. finally catches up with others and will provide GPS signal performance comparable to ESA’s Galileo and China’s BeiDou satellites that have already been broadcasting on L1C for many years. Military users get a little more signal power of marginal value, given the vulnerability of currently fielded military receivers and today’s jamming threat. Most commercial navigation users could care less about most of the other “bells and whistles” on GPS III. They already benefit from the increased accuracy and integrity delivered by Galileo and BeiDou. Longer satellite life, unified S-band Telemetry, tracking and commanding, a search-and-rescue payload, laser retroreflector arrays and a redesigned nuclear detonation detection system payload, although important to many other Pentagon missions, are of little value to the larger PNT user community. Longer satellite life also means that new satellite capabilities will be delayed for customers. At the 30th International Technical Meeting of the Satellite Division of The Institute of Navigation (ION GNSS+ 2017), held Sept. 25-28, in Portland, Oregon, the GPS Program Director, Air Force Col. Steve Whitney, announced that a full constellation of 32 GPS III and IIIF satellites is expected by 2034—fully 14 years from now.

All civil and commercial navigation users want are the L1C, L2C, and L5 navigation signals that Galileo and BeiDou already provide. All military navigation users want are secure LIM, L2M satellite signals and anti-jam, cyberhardened M-Code receivers. The L1M and L2M satellite signals are already broadcasting, but they are worthless without M-Code receivers, which are not yet in production. The real question is whether all these new features on GPS III are worth the growing cost of an increasingly complicated, multi-mission satellite. What GPS III really brings to the table is a growing appetite for the the Pentagon budget.

GPS satellite cost growth has not gone unnoticed by Congress. The House Armed Services Committee version of the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) cuts $15 million from the Space Force’s $627.8 million procurement request and another $10 million from its research and development request of $263.5 for the GPS III satellite for “unjustified cost growth.” With escalating unit production costs and longer development and production timelines, will the U.S. be able to afford and be able to wait for the next block of GPS satellites purchased by the Air Force?

In addition to being late and expensive, GPS III is also being oversold as the solution to the program’s jamming woes. In an article in the April 2020 edition of National Defense, Gene McCall, former Air Force Scientific Advisory Board (AFSAB) chairman who led the 1996 AFSAB study of GPS anti-jamming shortfalls wrote:

“GPS signals are essential to a vast array of critical infrastructure, transportation and emergency services applications. Signal disruption by U.S. adversaries, terrorist groups, criminals and ordinary people who don’t want to be tracked are on the rise. So, when an Air Force general told CBS News last year that GPS III will be ‘eight times more jam-resistant’ than today’s GPS, it gave the impression that the government had the matter well in hand. Nothing could be further from the truth . . . While such misleading sound bites may help support funding requests for the expensive—and essential—GPS III program, they are harming national and homeland security.”

Meanwhile, Back Inside the Beltway

President Donald Trump’s administration is now so concerned about the nation’s dependence on such a fragile and antiquated GPS system that the president issued an Executive Order on Feb. 12 to develop a plan to test the vulnerabilities of critical infrastructure systems, networks and assets in the event of disruption and manipulation of PNT services—which are almost entirely based on GPS.

Since it invented GPS, the Pentagon has had a 50-year head start on PNT services. It’s a national travesty that it took a presidential order to begin to get to the bottom of the mess the Pentagon’s GPS managers have created by building, fielding and marketing a system it characterizes as extremely vulnerable to other federal agencies, U.S. industry, the American people and the world at large. This is unacceptable behavior and it has not gone unnoticed on the world stage. In fact, this is one of the main reasons why other nations’ satellite navigation systems have sprung up like weeds across the world. Even our closest allies no longer trust GPS—ergo the European Union’s Galileo program, which boasts a Public Regulated Service (PRS) to deal with jamming and spoofing threats.

GPS Is No Longer the Best Game in Town

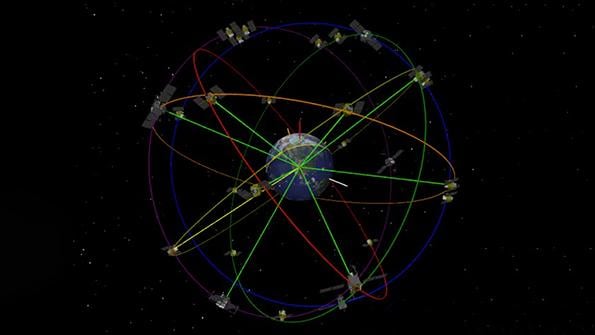

While the Pentagon’s fixation on Ligado has raged in Washington over the past decade, Europe and China have been hard at work, catching up to and even surpassing our civil/commercial GPS capabilities. Galileo went operational worldwide in 2016, and currently has 22 satellites on orbit. BeiDou launched the final BeiDou 3 satellite June 23, giving it 35 satellites for worldwide operations. Meanwhile, GPS currently has 31 operating satellites. China started deployment of its phase 3 satellites in 2015 and finished launching 30 BeiDou 3 satellites in five years. In contrast, the U.S. embarked on its phase 3 program in 1997, has launched three GPS III satellites and hopes to complete the program by 2035. Both China’s BeiDou and Europe’s Galileo provide the same level of single-frequency performance as GPS, but their systems offer improved signal structures, flexible navigation data messages and higher accuracy since they provide more civil signals for receiver-calculated ionospheric corrections.

Since February 2015, China and Russia have been establishing a cooperative framework between their satellite navigation systems, BeiDou and Glonass. The agreement was signed in November 2018 and ratified by Russia in July 2019. Dana Goward, president of the Resilient Navigation and Timing Foundation noted in an Aug. 23, 2019, article in National Defense magazine:

“Having such a large and robust satellite system could also add to the two nations’ predilection for interfering with international GPS signals over broad areas. Chronic GPS disruption by Russia and China in northern Scandinavia, the Black Sea, eastern Mediterranean, South China Sea, and elsewhere could become far more common and widespread as the Sino-Russo mega-constellation becomes more robust and the partners more emboldened. Jamming and spoofing GPS has tactical and strategic advantages for Russia and China. It can support a specific mission or goal, such as protecting VIPs or harassing NATO wargames. At the same time, it demonstrates the vulnerability of GPS and shows U.S. and European weakness. With a combined and more robust system in place, jamming and spoofing GPS would also encourage users to switch away from using the U.S. system and toward using Glonass-BeiDou.”

What is even more amazing troubling is that Air Force reconnaissance aircraft now use China’s BeiDou and Russia’s Glonass as backups to the U.S. GPS. At a McAleese and Associates conference in Washington on March 4, Gen. James “Mike” Holmes, head of Air Combat Command said, “My U-2 guys fly with a watch now that ties into GPS, but also BeiDou and the Russian [Glonass] system and the European [Galileo] system so that if somebody jams GPS, they still get the others.” This U.S. revelation was front-page news in the South China Morning Post, which went on to include the following: “Zhou Chenming, a military analyst in Beijing, said that as BeiDou was an open system, it would be easy to integrate a receiver chip into a watch and be able to access it. BeiDou has positioned itself as a commercial global positioning service provider,” he said. Also, unlike GPS, which was operated by the U.S. Air Force and sometimes restricted services to commercial users, technically the BeiDou system did not control the signals from its satellites, Zhou said. China developed the satellite navigation system primarily for use by its military, the People’s Liberation Army, which had previously relied on GPS. However, it has since been expanded for commercial use around the world, and once fully functional is expected to have an accuracy of 10 cm (4 in.) compared to the GPS’s 30 cm.

BeiDou goes one step further. It is the first global satellite navigation system that includes integrated two-way messaging. BeiDou appears to be venturing into the lucrative location-based services market. But will those services be optional or mandatory? Will China have the same personal privacy standards as the U.S. and its allies? This is highly doubtful, given their approach to the novel coronavirus (and government social control and surveillance policies generally), allowing individuals to be tracked using their cell phone signals.

Wither the “Gold Standard”?

In their May 6, 2020, testimony at the Senate Armed Services Committee hearing on Defense Department Spectrum Policy and the impact of the Federal Communications Commission’s Ligado decision on national security, Pentagon leaders claimed that U.S. GPS space capability was the “gold standard,” and further suggested that GPS must be protected (allegedly from Ligado) or the world may no longer regard GPS as the global standard for PNT excellence. Unfortuately, these claims just do not ring true anymore. The Chinese and Europeans have more and better civil signals than GPS now and will for many years to come. The GPS L1C/A signal is so old and outdated compared to Galileo’s EI and BeiDou’s BIC, it is now, unfortunately, tarnished—akin to a MS-DOS command prompt in a Windows world.

How Can the U.S. Get out of This Mess?

1. Transition GPS to the civil or commercial sector and focus the Pentagon exclusively on military PNT.

Given the Pentagon’s inability to effectively manage GPS program costs and schedule, keep pace technologically with its civil competitors, and deliver M-Code military receivers over the past 23 years, it is time to consider a new program structure. The U.S. should transition the largely civil and commercial GPS program to a commercial service provider under civil agency oversight. This would free up precious Pentagon talent and funding to pursue and deliver warfighting PNT priorities exclusively.

According to the European Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) Agencies October 2019 GNSS Market Report Issue 6, “The global installed base of GNSS devices in use is forecast to increase from 6.4 [billion] in 2019 to 9.6 [billion] in 2029, with the Asia-Pacific continuing to account for more than half of the global GNSS market.” China clearly understands this and is preparing to dominate that market. In contrast, the Pentagon and its allies plan to field one million GPS military sets by 2035. By end of the decade, military users will only represent 1/1,000th of a percent of the total user base. Satisfying the other 99.99% of the customers is a huge distraction for the Pentagon when it comes to delivering capabilities to the warfighter. It has to be part of the reason the Pentagon has had difficulty delivering on GPS III, OCX and M-Code user equipment.

The Defense Department has been subsidizing the U.S. and mostly international commercial markets far too long by providing free service at the expense of other federal and the Pentagon priorities, and over the longer term, jam-resistant, battlefield-tested PNT. The Pentagon is ill-suited to manage what has largely become a global civil/commercial utility, like electric power and telecommunications. Just as the Pentagon transitioned the Arpanet into commercial hands to become the internet and generate trillion-dollar companies and millions of jobs because of the power of our free market system, it is time for the Pentagon to do the same for satellite-based positioning, navigation and timing. Furthermore, over the past 45 years, the Pentagon’s GPS satellite cost has grown from $20 million each to almost one-half billion dollars apiece. America’s booming $330 billion commercial space industry could easily slash that cost, be more responsive to customer needs and be far more efficient than the Defense Department, while delivering improved capabilities faster and turning a profit to boot. The Defense Department could be freed up from the responsibilities of simultaneously meeting military and commercial needs and could finally focus on deploying a brilliant and highly effective wartime PNT system that our troops can depend on with their lives.

2. Implement GPS Receiver Standards

The GPS community should be focusing its efforts on designing, marketing, selling and fielding GPS receivers that can operate safely and interference-free in the ever-changing spectrum environment. It is difficult to believe America’s GPS receiver manufacturers do not provide and GPS users do not demand information on receiver performance and how their receivers operate in a standardized way across the market. Appliances have energy efficiency ratings. Automobiles have fuel economy ratings. Even auto tires have ratings. Shouldn’t GPS receivers have accuracy and interference ratings so consumers can base their product choice with their needs and budget, knowing what they are actually purchasing?

At a minimum, the FCC should implement GPS Receiver Standards as a part of a larger equipment authorization protocol that accomplishes the following:

- Verifies the GPS receiver operates correctly in the presence of out-of-allocated band interference (off-tune rejection).

- Verifies the GPS receiver operates correctly in the presence of allowed allocated in-band interference current in the FCC Rules (Iridium, Globalstar, AWS-1, AWS-3, UWB, ATC, etc.).

- Verifies the ability of the receiver to notify the operator when it believes it is experiencing interference, jamming or spoofing that could result in hazardous or misleading information.

3. Repurpose the Positioning, Navigation and Timing Advisory Board (PNTAB)

The PNTAB has become an almost independent body that often supplants government authority. The PNT is chartered under the Federal Advisory Committee Act (FACA) to NASA. According to its website, the PNTAB current consists of 17 Special Government Employees, eight representatives, five of whom are foreign nationals, and four subject-matter experts—all from private life—and an executive who is a government civil servant. These GPS “insiders” provide limited forward-looking vision to the program. In its latest online report, the PNTAB made over 40 recommendations, most of which will never be considered or implemented since many exceed the authority of those who receive the recommendations.

Most troubling is that the almost singular focus of the PNTAB on spectrum—even though the body has no spectrum experts—has been marginalizing and undermining Ligado. These topics have dominated the PNTAB’s agenda and thought process over the past decade. The PNTAB even wrote a letter directly to the chairman of the FCC expressing their spectrum and Ligado concerns. This is extremely unusual, since the PNTAB’s charter under the FACA says:

- “Description of Duties: The PNT Advisory Board will provide advice, as requested by the PNT EXCOM and through NASA, on U.S. PNT policy, planning, program management, and funding profiles in relation to the current state of national and international space-based PNT services.”

- “Official to Whom the Committee Reports: The PNT Advisory Board Chair or Vice-Chair will report findings, recommendations, and tasking progress to the PNT EXCOM, of which NASA is a member.”

This amount of focus on a single topic by a FACA doesn’t serve the government’s long-term interests. It now appears that the PNTAB has pushed its “Death to Ligado” agenda onto the Pentagon’s plate, which is certainly not healthy. Most of the arguments the Pentagon uses to undermine Ligado originated in the PNTAB. Do NASA, the Pentagon and the Transportation Department run the FACA? Or for PNT-related matters, does the FACA run those government agencies?

The U.S. doesn’t need a separate FACA full of longtime GPS/PNT experts who have fairly diverse backgrounds, but very common opinions and narrow interests. There is very little diversity of thought in the group. The GPS community would be better served by assigning existing FACAs specific tasks rather than letting the current PNTAB decide the topics on which it wants make recommendations. This narrowly focused approach on the singular issues of spectrum and Ligado has allowed the PNTAB to neglect the most fundamental issues facing GPS since inception. Meanwhile, the PNTAB has idly watched the U.S. drop from first to third in world satellite-based PNT leadership. Simultaneously, they have watched our military PNT capabilities diminish against every new cyber and jamming threat from our adversaries. How is it possible for U.S. GPS to lose such ground against our competitors and adversaries when it has such an illustrious group of experts providing advice? It is only through the PNTAB’s abject neglect of the nation’s true priorities—which are NOT dealing with radio-frequency spectrum and killing Ligado.

The PNTAB has outlived its usefulness. It should be repurposed in a way that focuses on integration with modern technological innovation, harnessing the creative power of industry, demonstrating U.S. leadership in space and re-grounding GPS on its original and most important reason for existence—helping America wage and win military conflicts.

4. Build a Backup for Civil/Commercial GPS

Given that GPS, especially civil GPS, is so vulnerable to jamming and spoofing, it makes a lot of sense to have a backup system. China has already included the existing Loran-C infrastructure into its comprehensive PNT architecture with BeiDou. It is logical that the U.S. should implement a similar approach. Unfortunately, although the Transportation Department has looked at this idea, it hasn’t funded it. In fact, under the Obama administration, the U.S. Coast Guard terminated the Loran-C program in 2010 and started dismantling its infrastructure. However, in 2015, the Coast Guard began experiments with an enhanced Loran or eLoran as a potential backup for GPS.

According to a Nov. 23, 2015 GPS World article, eLoran has the “accuracy, availability, integrity and continuity performance requirements for maritime harbor entrance and approach maneuvers, aviation non-precision instrument approaches, land-mobile vehicle navigation and location-based services. ELoran is a low-frequency radio-navigation system that operates in the frequency band of 90-110 kHz. ELoran is built on internationally standardized Loran-C, and provides a high-power PNT service for use by all modes of transport and in other applications. ELoran is an independent dissimilar complement to GNSS. It allows GNSS users to retain the safety, security and economic benefits of GNSS even when their satellite services are disrupted.”

According to Norway’s Jens Hoxmark, a member of the Resilient Navigation and Timing Foundation, eLoran, now operating in Russia and China, is not the only way to provide navigation timing and synchronization. A 5G network can do the same thing. In fact, an eLoran network can broadcast essential information if 5G becomes unavailable or the user is outside range of the 5G network. Putting inertial, GPS, 5G, eLoran navigation together in a single package provides an incredibly robust, redundant, jam- and spoof-proof civil navigation capability—without military-grade encryption or hardware. Just imagine if one did put that combination into a military-grade system. The biggest roadblock is that eLoran is not funded.

In the National Timing Resilience and Security Act of 2018, Congress authorized—subject to the availability of appropriations—the transportation secretary to provide for the establishment, sustainment, and operation of a land-based, resilient, and reliable alternative timing system for GPS, which envisioned using eLoran for this purpose. The annual cost of this yet-unfunded authorization is $25 million per year.

Perhaps Ligado could be convinced to fund eLoran in some way the first few years to get it going and help plug a serious hole in the U.S. PNT architecture. This would engender collaboration and cooperation that is much needed and overdue.

The Way Ahead

Moving forward, it will be far more efficient and effective to put all the elements of GPS into their own lanes rather than the current navigation stew funded by the Pentagon. Commercial GPS interests are best served by America’s vibrant commercial space sector. Military GPS needs are best served by the new U.S. Space Force. To keep something like this long Ligado saga from happening again, GPS sorely needs receiver standards so that consumers will know exactly what their receiver does and doesn’t do in what can be a hostile spectrum environment. The PNTAB has outlived its original usefulness and should be repurposed. If GPS is as fragile as its proponents say, it truly needs a backup. But, then again, shouldn’t every important system have a backup anyway? Forward-looking public and private innovators can come together to advance this approach. GPS needs to lose its tight grip on the past and come to grips with today’s reality as it looks toward the future.

Daniel S. Goldin is an engineer who served as NASA administrator under three U.S. presidents, from 1992 to 2001. He has no financial affiliation with Ligado Networks.

The views expressed are not necessarily those of Aviation Week.

Comments