USAF Warns F-35 Reengine Decision Needed For Health Of Industrial Base

The U.S. Air Force is aggressively pushing for the reengining of its Lockheed Martin F-35 fleet while simultaneously proceeding with a highly classified approach to powering its next-generation fighter, arguing it is not just the aircraft that needs approval for the new powerplants—it’s about the health of the industrial base as well.

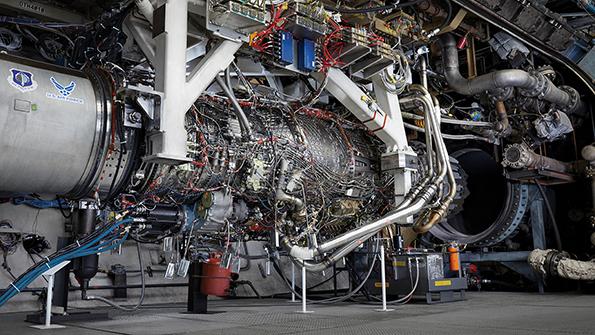

The service’s Adaptive Engine Transition Program (AETP) is reaching its final stages, with GE Aviation and Pratt & Whitney’s three-stream propulsion systems undergoing evaluations ahead of an expected decision next year. The Air Force’s F-35A variant currently lacks power and sufficient thermal management capacity for upcoming technological upgrades, and Air Force Secretary Frank Kendall said he supports an adaptive engine to provide the thrust and range he wants.

- Sixth-generation program faces sourcing decision soon

- U.S. Air Force secretary wants F-35 engine choice next year

- Some lawmakers raise cost concerns

AETP, and the forthcoming Next-Generation Adaptive Propulsion (NGAP) program for the sixth-generation Next-Generation Air Dominance (NGAD) fighter, are the only efforts in the U.S. looking at game-changing fighter engine designs. Without sustained funding to proceed, “that portion of the industrial base will collapse,” said John Sneden, the director of the Air Force Life Cycle Management Center’s Propulsion Directorate.

While industry giants GE, Pratt and Rolls-Royce will not be going anywhere in general, “where the direness comes in, I think, is this very thin sector, which is the advanced propulsion market, and the only thing I think we really have in that space right now is AETP,” Sneden said.

F-35 Decision Coming Soon

The U.S. Air Force first kicked off what would become AETP with the Adaptive Engine Development Program in 2012 before the follow-on AETP in 2016. For the adaptive program, GE developed the XA100 and Pratt developed the XA101. With such a long development program, Kendall said the time is now to finally make a decision.

“I don’t know how we’ll come out, but I think we need to make a decision about the future of the F-35’s engine and get on with it,” Kendall said in July at an event hosted by the Potomac Officers Club, adding he “very much desires” an AETP-like solution for additional range.

This decision will come in the Air Force’s fiscal 2024 budget request to be released next year, potentially kicking off another five-year program to move through the engineering and manufacturing development (EMD) phase. This will include flight testing and integration, with production at the end of the decade, Sneden said. There are no plans yet for a flight demonstration, but the program is ready to move to EMD and ensure it is “tested and validated in every possible way,” he added.

While Congress has been pushing the Air Force to move ahead with AETP for the F-35, calling for a plan for installation by 2028, other lawmakers have recently raised concerns about the cost. This will be several billion dollars, Kendall said, in addition to the ongoing research and development funding.

“I don’t want to limp along, spending R&D money on a program that either we can’t afford or that we’re just not going to get agreement on among the different services,” Kendall said. “So we have got to get to a decision on it.”

The Air Force has hoped the Navy would express interest—with the AETP offerings able to fit in the F-35C, though not currently in the Marine Corps’ F-35B. However, the Navy has not publicly expressed interest in the engines. GE, for example, says it has designed its XA100 from the beginning to fit in the F-35C and has had ongoing discussions with the Navy, says David Tweedie, vice president and general manager of GE’s Edison Works Advanced Products unit. Fitting the engine offering to the distinct F-35 variants was an additional challenge because of different characteristics of the C model—it is bigger, has more tightly packaged requirements in the engine bay and has a larger tail hook. However, GE’s engine offering has a 100% part-number commonality for the A and C models, Tweedie says, and the company is starting to research adapting it for the B model.

“We’re doing our best to make sure that we have a compelling offering for the Navy,” Tweedie says.

Spreading out the cost will help, with the bill expected to reach up to $6 billion to bring on the new engine for the F-35A by 2030. Despite the price tag, however, Sneden argues the spending will be needed. If an AETP engine is not picked, the service could go with an upgrade to the current F135, like Pratt’s F135 Enhanced Engine Package, or other modifications that would still need to be bought.

“Regardless of the path that we choose for the F-35, we’re going to spend a lot of money to get to where we need to be, whether it’s an upgrade to the current F135, the engine enhancement program, or if it’s an AETP engine,” Sneden said. “Our perspective is: ‘You can optimize for performance or you can optimize for trivariant commonality.’ We think the warfighter deserves the performance attributes that AETP can deliver. And frankly, what I’ll offer to you is that winning is expensive, and we can’t afford to lose.”

The Next Generation

Beyond the F-35, the Air Force is continuing development of future adaptive engines for the classified NGAD aircraft. The service expects to conduct preliminary design reviews of offerings from GE and Pratt this year ahead of a possible selection in 2024, Sneden said.

The Air Force will have to make a “resource-based” decision soon whether to move ahead with just one provider for NGAP, Sneden added, which would further limit competition and—if there is no progress on AETP—potentially create a monopoly in the advanced fighter engine market.

For NGAP, the Air Force is focused on two priorities: providing the power that will be needed to “enable options” for the sixth-generation fighter and accelerating industry’s technological prowess specifically through the use of digital engineering.

“So, in the future this will be the first engine system that we’ve had that actually got developed in a digital environment,” Sneden said.

The two offerings leverage the technology used in AETP with the three-stream architecture as a requirement, but they feature a different design and an overall “brand-new system beyond what we see in AETP,” Sneden said. Like the XA100 and XA101, the two companies are taking a slightly different approach.

“Just like . . . their approach to AETP is slightly different—different technical solutions, one for GE, one for Pratt & Whitney—we’re seeing the same thing on NGAP,” he said. “Right now this is something we’re all focused on: How do we keep the advanced propulsion industrial base viable? How do we keep it competitive? We think that having a nice competitive market is a gateway to keeping costs low and keeping innovation essentially at our fingertips, but right now we kind of see a lot of that trade space starting to come down and we’re very concerned with it.”

Comments

Both Pratt and GE have done similar things for several different tactical aircraft for decades now which has benefited them and the airframe manufacturers.

Pratt&Whitney and GE, are the only engine companies in the USA with the technical and financial resources to advance [military] engine technology. And because competition improves the breed, it is vitally important to keep these two, best in class, companies viable entities.

Am glad to see that the Pentagon is apparently thinking along the same lines.