On March 11, 2018, at about 1908 EDT, an Airbus Helicopters AS350 B2 (N350LH), lost engine power during cruise flight, and the pilot performed an autorotative descent and ditching onto the East River in New York City. The pilot survived, sustaining minor injuries, but all five passengers drowned.

The flight was operated by Liberty Helicopters Inc., per a contract with NYONair (originally called New York On Air). Both companies considered the flight to be an aerial photography mission operated under FAR Part 91. In the NTSB’s subsequent meeting with Liberty’s chief pilot, there was much discussion about what would otherwise appear to be a commercial Part 135 charter flight operating under the auspices of the lesser supervised Part 91 due to a regulation that allows for such photographic flights.

VFR weather conditions prevailed, and no flight plan was filed for the intended 30-min. local flight, which departed from Kearny Heliport, Kearny, New Jersey, at about 1850. It proceeded over the Passaic River and the North Newark Reach to Bayonne, where it crossed eastbound toward the Statue of Liberty.

The operator allowed the five passengers (one in the front seat, four in the rear) to take photographs of various landmarks while they extended their legs outside the helicopter during portions of the flight. Another Liberty helicopter took off at approximately the same time and the two flew within sight of each other for, at least, the first part of the flight. These aerial photo shoots are advertised as “shoe selfies.”

The accident pilot later talked about the amount of moving around and shuffling that was being done as the passengers took pictures of the Statue of Liberty and other landmarks. Coincidentally, much promotion of the service is actually done by passengers who post their images on Instagram and through Snapchat type messages. For the accident and other FlyNYON flights, Liberty removed the AS350 B2’s two right and front left doors and the left sliding door was locked open.

Briefing

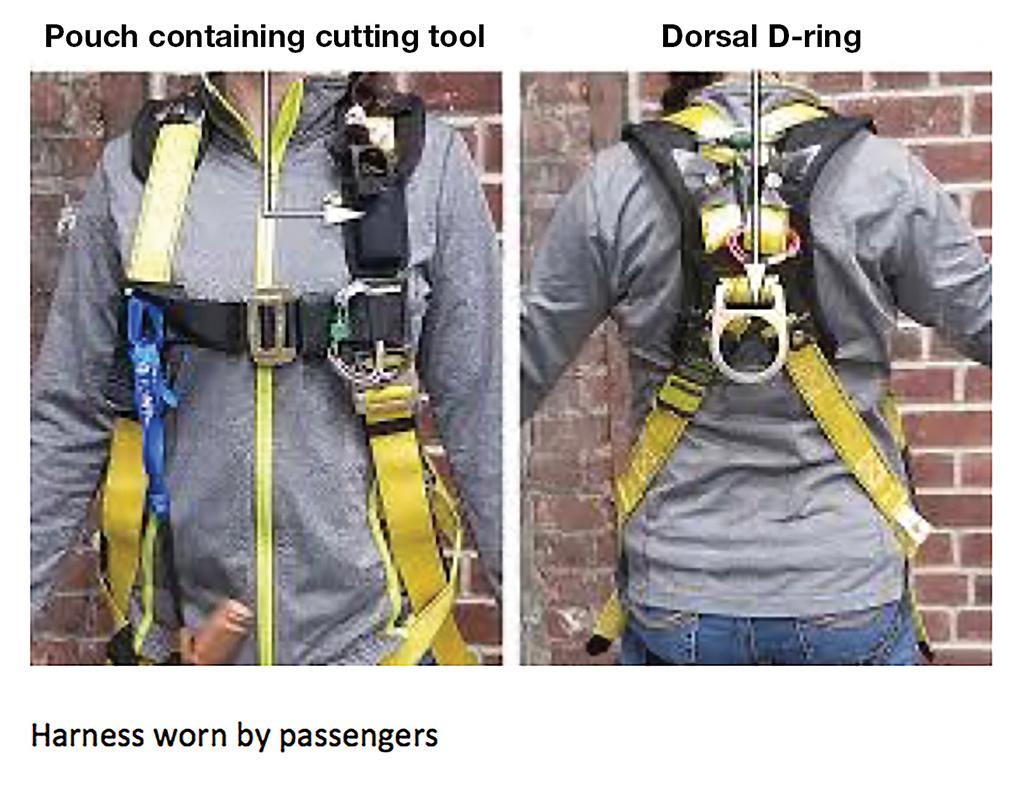

Prior to the accident flight’s departure, each passenger was fitted with a NYONair-provided harness/tether system that NYONair developed with the intent to prevent passengers from falling out of the helicopter. The system used on the accident flight consisted of a full-body, workplace type fall-protection harness that was secured with a locking carabiner to a tether strap, the other end of which was secured to an anchor point in the cabin. Each passenger also wore the helicopter’s installed, FAA-approved restraints while seated. The pilot (who was seated in the front right seat) wore only an installed, FAA-approved restraint.

According to Liberty personnel interviewed by the NTSB, the passengers went to the harness room to be fitted and were briefed so that they fully understood the loading process. They made sure nothing was in the passengers’ pockets and then put all their belongings in a bin and double checked that step. They said they explained exactly what they were doing when harnessing the passengers.

The passenger representative said she explained to the passengers that they had a cutter on the left side of the harness to be used in case of an emergency. She stated she would always review the information with the passengers and ask, “What is the cutter there for?” She said all of the accident passengers knew they had a cutter and they all knew how to use it if necessary.

When asked if she specifically remembered going over all those details with the passengers on the accident flight, she stated, “Yes, yes.” When asked to confirm the cutter was on the left side of all the harnesses, she replied, “Yes.” She also stated that all the harnessing was done at the terminal, before they loaded the passengers into the vans to take them to the heliport.

Cabin Set-Up and Videos

After the flight departed, and consistent with the standard operating procedures (SOPs) used for FlyNYON flights, the passengers were allowed (when instructed by the pilot) to position themselves to extend their legs outside the helicopter. The two passengers who had been seated in the rear inboard seats removed their FAA-approved restraints and sat on the cabin floor, but wearing their harness/tether systems. The passengers seated in the outboard seats were allowed to rotate outboard in their seats. To enable such freedom of movement, the SOPs allowed the passengers to wear their lap belts adjusted loosely and the shoulder harness routed under their arms.

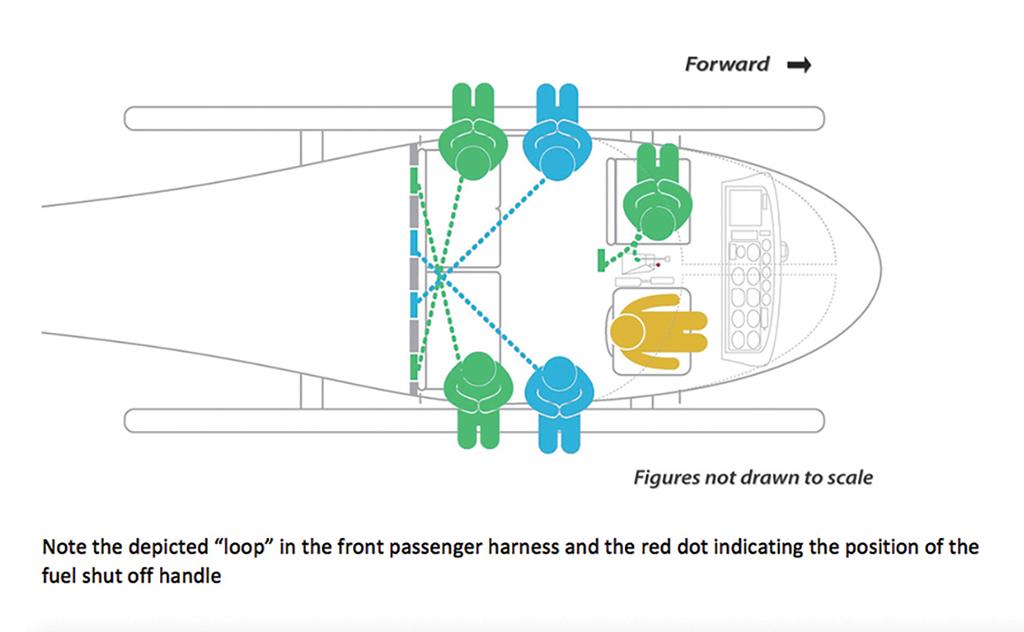

The fifth passenger was seated in the front left seat of the helicopter and had been instructed that the way to take the “shoe selfies” was to lean back, raise his feet and shoot the picture.

Videos show that once the helicopter was airborne, passengers began using their personal electronic devices (PEDs) to shoot videos and photos. Throughout the flight, it appeared the passengers were sharing photos over a cell network to social media photography/video apps and, in some instances, were interacting with one another. The number of “shoe selfies” taken were not specifically quantified but were numerous and frequently taken near landmarks.

A review of onboard video showed that, when the flight was proceeding northwest over Manhattan toward Central Park at an altitude of 1,900 ft., the front passenger, who was facing outboard in his seat with his legs outside the helicopter, leaned back several times to take photographs using a smartphone.

The onboard GoPro video showed that, each time he leaned back, the tail of the tether attached to the back of his harness hung down loosely near the helicopter’s floor-mounted controls. At one point, when he pulled himself up to adjust his seating position, the tail of his tether remained taut but appeared to pop upward. Two seconds later, the helicopter’s engine sounds decreased, and the helicopter began to descend.

The Ditching

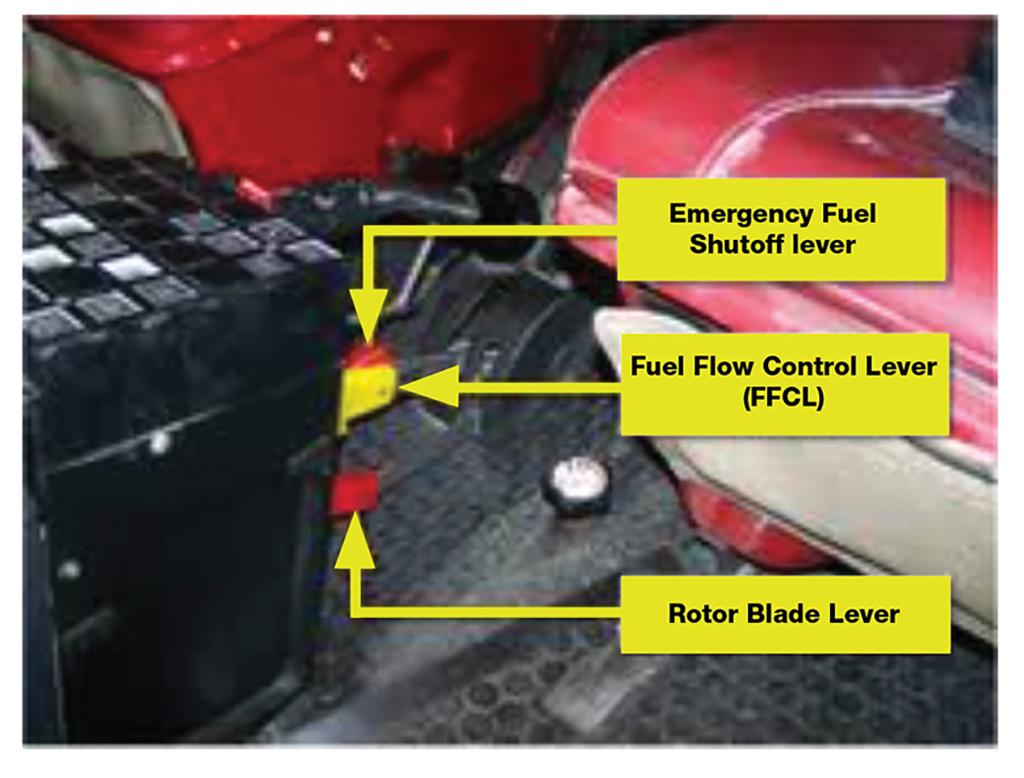

As the pilot performed the emergency procedures to execute an autorotation and address the apparent loss of engine power, he noticed that the fuel shutoff lever (FSOL) was in the closed position. It had been inadvertently moved to that position by the tail of the front passenger’s tether, which had become caught on it.

Although the pilot pushed the FSOL down to restore fuel flow and attempted to relight the engine, power was not restored. In his post-accident debrief, the pilot stated that the engine responded immediately with a temperature increase, but the aircraft was too low to allow sufficient time to come to power.

The pilot pulled the activation handle to deploy the helicopter’s emergency flotation system, and ditched the aircraft on the East River.

The flotation system installed on the AS350 B2 contains two pressurized gas reservoir assemblies that inflate, via hoses, six skid-mounted floats. Three floats are mounted to each side of the skids; each float contains two chambers. The floats on both sides of the skids are identified as “forward,” “mid” and “aft,” i.e. “left-forward” identifies the forward-most float installed on the left skid. Each float is packaged within its own float cover.

Credit: NTSB

The reservoir assemblies are mounted to the airframe via loop clamps. One reservoir assembly is mounted underneath the left baggage compartment while the other is mounted underneath the right baggage compartment. Each assembly is composed of a valve and a cylinder. The valve is opened via a mechanical pull cable system that the pilot activates with a handle mounted on the cyclic stick, near the base of the cyclic grip.

The pilot deploys the floats by pulling the activation handle aft. The float activation handle is offset from the cyclic grip by about 32 deg. to the right to prevent interference with the grip when the activation handle is pulled aft. A shear pin, installed within the activation handle, is intended to prevent inadvertent activation of the float system

When asked to describe how the float system was deployed during the accident flight, the pilot stated that when it came time to deploy the floats, he “took [his] left hand off of the collective and placed it on top of the cyclic . . . and gripped the [activation] handle with [his] right hand and pulled it back fully and completely.” He stated that he heard a “pop” sound, which to him indicated that the float system deployed, and that “after pulling the [activation] handle, [he] returned [his] hands to the regular positioning and grip on the collective and cyclic.” The pilot stated that there was extra drag after the floats had deployed and that he could see parts of the left front float and right front float after the deployment.

Going Under

However, the floats did not fully inflate on one side, and as a result the helicopter rolled right in the water and became fully inverted and submerged about 11 sec. after it touched down.

The pilot was able to release his restraint while under water and successfully egress from the helicopter. Tragically, none of the passengers were able to do so.

A medical report stated that the pilot had eight abrasions to his left knuckles, and contusions inside his right hand’s palm. He said a bruise on his right hand between his thumb and index finger was caused by squeezing the cyclic prior to impact. He also had a cut at the bottom of the knuckle for his left index finger from actuating the emergency fuel shutoff lever back to the cockpit floor.

The onboard GoPro showed that all passengers survived the landing on the water. Their attempts to unhook the harnesses and move out were also recorded in detail as the cabin sank and filled with water. The recording ended with the cabin becoming too dark to discern what was happening as it filled. Water impact occurred at about 1908. Rescue divers arrived 30 min. later.

The accident helicopter remained submerged until March 12, and once recovered revealed no evidence of an inflight break up. No major components were missing. Two witness videos captured the ditching and the GoPro video recorder was recovered from the accident helicopter as well.

The Findings

After examining all the information collected by its investigators, the NTSB determined the probable cause of the accident to be Liberty Helicopters’ use of a NYONair-provided passenger harness/tether system, which caught on and activated the floor-mounted engine fuel shutoff lever and resulted in the inflight loss of engine power and subsequent ditching.

Furthermore, it found that contributing to the accident were Liberty’s and NYONair’s “deficient safety management which did not adequately mitigate foreseeable risks associated with the harness/tether system interfering with the floor-mounted controls and hindering passenger egress” and Liberty allowing NYONair to influence the operational control of its flights for the latter.

In addition, it faulted the FAA’s “inadequate oversight of Title 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 91 revenue passenger-carrying operations.”

And finally, it found that contributing to the severity of the accident were the rapid capsizing of the helicopter due to partial inflation of the emergency flotation system and the use by Liberty and NYONair of a harness/tether system that hindered passenger egress.