A balloon pilot has the ability to make the balloon rise by heating up the air within the envelope, but there is a time delay between activating the burners and creating enough buoyancy to begin rising.

FAA Advisory Circular 90-66B, Non-Towered Airport Flight Operations, recommends that pilots should monitor the CTAF when passing within 10 mi. of an uncontrolled airport, and self-announce one’s position and intention between 8-10 mi. upon arrival. Self-announce is important to convey your identification, position, altitude and intended flight activity.

Communications on CTAF should be limited to safety-essential information regarding arrivals, departures, traffic flow, takeoffs, and landings. It is recommended to use the correct airport name as identified in aeronautical publications at the beginning and end of your self-announced traffic position report.

Since transient aircraft may not know local ground references, all pilots should use standard pattern phraseology, including distances from the airport. Your identification may include aircraft type to aid identification but should not use paint colors.

Non-IFR-rated pilots will not understand radio calls from IFR traffic using IFR terms such as “procedure turn inbound.” It is better to provide specific direction and distance from the airport, as well as your intentions at the completion of the approach.

There is a special precaution in the advisory circular that use of the phrase, “Any traffic in the area, please advise,” is not a recognized self-announce position and should not be used under any condition.

Right-of-Way

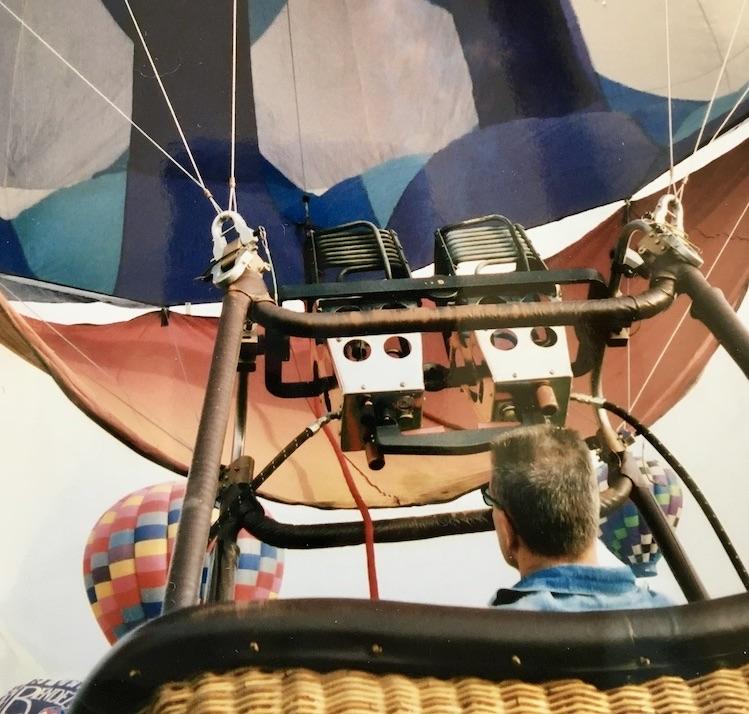

FAA regulations stipulate the right-of-way rules. When aircraft of different categories are converging, balloons have the right-of-way over any other category. It is easier to remember this right-of-way rule if you understand the lack of maneuverability of a balloon. The pilot can apply heat to the balloon envelope to make it rise, but the reaction time between hitting the burners and the sufficient warming of the air in the balloon envelope is anything but instantaneous.

A balloon pilot can pull the vent to allow hot air to escape, thus hastening the balloon’s descent rate, although this control input is usually reserved for the final moments during a landing. Otherwise, the balloon’s movement is dominated by drifting with the wind.

Gliders have priority over an airship, airplane or rotorcraft. A glider, including the tow aircraft during towing operations, has the right-of-way over powered aircraft. If both airplanes and gliders use the same runway, the glider traffic pattern will be inside the pattern of the engine-driven aircraft. An airship, with its limited maneuverability, has the right-of-way over an airplane or rotorcraft.

Helicopters intending to land on a marked helipad or suitable clear surface must avoid the flow of fixed-wing traffic. When helicopters are using the runway, a suitable traffic pattern should be flown that does not conflict with any other fixed-wing traffic. This pattern may be similar to the fixed-wing traffic pattern but at a lower altitude and closer to the runway.

Unique Procedures

Each of the aircraft at an uncontrolled airport may have unique procedures, training needs and limitations that will affect how much time they need on a runway as well as the type of traffic pattern they need to fly. Each of us can better anticipate and coordinate in the traffic pattern if we have a better understanding of these issues in dissimilar aircraft.

For example, pilots working on the single-engine land commercial pilot certificate need to practice the power-off 180-deg. accuracy approach. The pilot-trainee will pull the power to idle while on the downwind leg and time the turn to base and final as well as trying to determine the key moments for deployment of the flaps to touch down on a pre-determined spot on the runway. This training maneuver requires concentration and constant decision making.

Pilots training in single-engine land aircraft may also be practicing a variety of short-field and soft-field landings and takeoffs. After each landing an astute trainee will need to properly reconfigure the aircraft. This important task is best accomplished during a stop-and-go.

Those of us puttering around the traffic pattern in taildraggers have unique limitations. Until you’ve sat in the cockpit of a classic taildragger such as the Stearman you can’t appreciate the lack of visibility over the nose. This is why many taildraggers need to perform continuous S-turns during taxi in order to see forward down the taxiway. Likewise, there is no visibility over the nose on the initial takeoff roll.

While the viewing angle upward and directly sideways is unobstructed by any cockpit obstruction in the Stearman, the viewing angle forward is almost completely obstructed by the engine and the wings. This is especially challenging during final approach and into the flare.

Another challenge in the situational awareness for a pilot in these types of aircraft is the auditory environment, with the roar of the engine and the pounding prop wash. Even with modern headsets this is an adverse auditory environment that impedes a pilot’s ability to hear.

Many gliders and old taildraggers are not equipped with radios. That means they won’t be making position reports on CTAF, nor will they be able to hear you making self-announced position reports. It also means they won’t have a transponder or ADS output signal, thus your TCAS or ADS-B won’t reveal them. This requires additional vigilance while operating in the traffic pattern at a non-towered airport.

Further procedures for operating around gliders and helicopters, in Part 3 of this article.

To read Proper Procedures At Uncontrolled Airports, Part 1, click here.