Part One of Three Parts

Operating in Asia during the COVID-19 pandemic is challenging for business aviation operators, but it isn’t impossible.

“Most countries appear, at first glance, to have shut their borders entirely,” said Aljoscha Subasinghe, business development manager for Asia Flight Services Co. Ltd., in Bangkok, “but usually there is enough room in the regulations to allow for certain types of visitors, such as business travelers invited by a local entity, to apply for visas and other entry documents.”

A year after the international lockdown in response to the coronavirus, that as of April 6 had infected 131.5 million people and claimed 3 million lives, according to Reuters News Service, the world struggles to contain COVID 19 and get back to business. Asia is no exception, and while airline service there has been drastically reduced--as it has everywhere on the planet--business aviation continues to operate, though within now-familiar restrictions, such as mandatory quarantining of crew and passengers for up to 14 days. (As we’ll see, there are workarounds for crew-only positioning flights and a handful of locations where crew-rest overnights are possible--but they’re in the minority.)

Things are opening up--but slowly, as countries take measures to counteract surges of infections. In states that have managed to reduce the infection rate, the public health strategy has been to prevent the likelihood of “imported” cases from outside national borders.

Taiwan, for example, has been successful in containing the spread of COVID-19 largely because of its quarantine and immigration policies, allowing in only Taiwanese nationals and effectively banning visitation by citizens of other countries. Within the greater region, however, visitation strategies may be determined by whether a country or city-state is a transport hub, such as Singapore and Hong Kong. While Taiwan has stopped accepting transit flights as part of its lockdown, the island is not generally considered a hub or hot spot for transfers anyway. Meanwhile, imported COVID-19 cases have not been uncommon in Hong Kong because of its status as a transport hub.

Little Accord in Rules

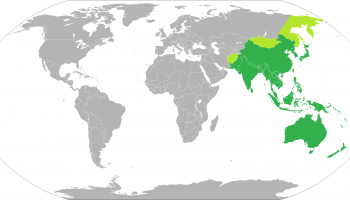

Business aviation flight crews planning missions into Asia will quickly learn that every country in the region has adopted its own set of rules for access during the pandemic. The unique concerns of national governments and diverse cultures that characterize the region have combined in a lack of regulatory harmonization regarding the entry requirements of individual countries. So not surprisingly, issues of sovereignty come into play, as each country responds to the pandemic in its own way.

Japan, for example, has chosen to forego lockdowns in lieu of “recommended curfews,” while more stringent actors like China have locked down entire cities, requiring residents to undergo COVID-19 testing if confirmed cases are discovered in their vicinities. Thus, the lack of harmonized regulations and policies containing the spread of the disease impedes the countries’ ability to create a free flow of travelers within the region, rendering the establishment of “travel bubbles” almost impossible. Also, because the Asian business aviation industry is not as mature as its counterparts in Europe and North America, governments tend to be slow responding to the requests and the needs of the community.

But as Jeffrey Chiang, chief operating officer of the Asian Business Aviation Association (AsBAA), points out from his Hong Kong office, there are no issues preventing operators from flying into Asia, other than the accepted responsibility for international flight crews to do their homework to stay updated with the latest restrictions and required documentation for entry. That research can often reveal some exceptions and even workarounds. “If business in a particular country is necessary,” Chiang says, “that is, if the trip is essential, the key is to…understand the entry and permit requirements of the destination country.” Because every nation maintains its own entry and quarantine policies, “this research is absolutely essential,” he adds. “Even in bigger countries like China, each city may have slightly different policies.”

South Korea, for example, still allows foreigners to enter the country, but avoiding a 14-day mandatory quarantine requires an invitation letter from a local company and an application for an exemption certificate through the South Korean government subject to the approval of relevant paperwork. “Since China implemented strict containment policies early on,” Chiang says, “it is opening up again because the disease has been largely contained and people within China are free to move around. According to some of our [AsBAA] members in China, domestic travel has been quite active.”

China’s ‘Great COVID Wall’

UAS International Trip Support’s regional director for China, Carlos Schattenkirchner, agrees. “Domestic traffic is picking up, both Chinese and visiting operators,” he told BCA from his office in Beijing. But the real challenge confronting those “visiting operators” is getting into the People’s Republic of China in the first place.

The pandemic has divided visitation into two categories: ferry flights with only crew on board and regular flights carrying passengers, Schattenkirchner said. “For the latter,” he explains, “it is almost impossible [to come in] at the moment. With passengers of any nationality--even Chinese--aboard, you need a special invitation letter and approval from the state council presiding over your destination.” Additionally, anyone desiring entry will need a new visa, as existing long-term visas issued after March 2020 were voided when the PRC imposed stricter rules at the beginning of the pandemic lockdown. “This makes it almost impossible for passengers to fly in on private jets,” Schattenkirchner said, adding that applicants should be prepared for the local councils to reject their requests, “as they have tended to do that anyway.”

On the other hand, deadheading in, crew only, is not as big of an issue, provided they have valid visas issued after March 2020 and are willing to undergo quarantine procedures: a minimum of 14 days in some locations and up to 21 in others. Note that quarantine hotels are selected by the local health authorities and there will be at least two COVID-19 tests administered while under quarantine, as well as frequent temperature monitoring.

Rumors continue to circulate that in order to get into the PRC, inoculations with the China-produced Sinovac or Sinopharm vaccines will be required. “As a result, “there has been a lot of confusion around this issue,” Schattenkirchner said. “The truth is that, while applicants who can prove they’ve received a Chinese vaccination will have easier access in terms of obtaining a visa and less documentation will be required, it otherwise makes no difference. Toward the end of the year, it might be a benefit, but for now, it only assists the visa process.” In other words, it’s not a game-ender.

If they are not planning to enter China and remain for a visit, it may be possible for operators to perform quick turnarounds to pick up passengers and depart--all contingent, of course, on being able to convince the PRC authorities to issue landing permits. The clincher is that the crew must remain aboard the aircraft, and as long as they do so, they’re good to go, Schattenkirchner says.

“The problem is that if anything happens on the ground--a passenger delayed, a maintenance issue, a crew duty time issue, any delays like this--everyone has to quarantine and then come under the control of the local health authorities from the PRC Center for Disease Control,” he said. “Once you leave the aircraft you are not under the aviation rules but the local disease control authorities, and this makes things really complicated.”

On the other hand, “once the aircraft is here and the crew has quarantined and tested multiple times [with negative results] and is released, you can fly domestically where there are not too many restrictions at the moment,” Schattenkirchner says. It’s doubtful, though, that many business jet operators would be willing to keep an expensive jet on the ground and its presumably highly paid flight crew cooling their heels in a quarantine hotel for 14 to 21 days.

Old Asia hand and contract pilot Pat Dunn’s advice is simple.

“Don’t go, because it will be a pain in the neck,” Dunn said. “Business visas have been canceled and crew visas are on a case-by-case basis. Only if you own a business in-country can you expect to be admitted. Then you need a visa--a new one every time you go--and existing ones can only be used to re-enter the queue for a new visa, so these are effectively one-shot visas. Even if you have a business [based] in-country, you will still have to quarantine in order to enter.”

While it would seem that entering China from Hong Kong might constitute a workaround, “To go to the mainland from Hong Kong you must transit through Macao and vice versa returning,” Dunn points out, “and you still have to have a visa to go to the mainland.”

The timeworn proverb dating from China’s dynastic past, “The mountains are high, and the emperor is far away,” comes into play here, too, as we hear tales of cities in the country where operators have been permitted to arrive, remain overnight to obtain crew rest, and depart the following day. Technically, this is illegal, but as one pilot, who requested anonymity, told BCA, “No one’s talking about it, but these things can be done. No one explains how they got there.”

But in the interest of international relations (and not getting that aforementioned expensive business jet impounded), it’s sensible to follow the rules. Also, it’s noteworthy that Seoul, traditionally an aircrew transfer and layover stop for transpacific flights, especially going in and out of China, has reportedly been getting more business lately.

Retrieving the necessary preflight planning information for trips into the PRC is complicated by the fact that there is not one official source (or web link) in the government bureaucracy. That is, each department impinging on entry into the country has its own portal, e.g., general entry rules, visa application, etc.

“The Chinese consulate or embassy in your country of residence can provide information,” Schattenkirchner said. “Our advice is to have good preparation and a local partner. Use your handler to have someone standing behind you. There are a lot of different authorities involved. Before the pandemic, an operator’s only requirement was the permit from the China Civil Aviation Administration--now the CAA doesn’t care as much since the priority is whether the local authorities will accept the flight. The process has changed with many stakeholders involved.”

Hong Kong in the Spotlight

One cannot approach the subject of China without considering the conflicted relationship between the mainland and its offshore possession, Hong Kong. Reverting to China after the UK’s 99-year lease on the island expired in 1997, the territory--now governed as a “special administrative region”--exists today as an anomaly: a capitalist economy embedded in one of the last remaining communist states.

Initially, the PRC kept Hong Kong at arm’s length, governing it under a policy of “one country, two systems.” After all, as the most powerful financial engine in Asia (and home to the largest concentration of high-net-worth individuals in the world), Hong Kong was generating billions of yuan for the coffers of mainland China.

But in recent years, the PRC’s fear that this freewheeling example of Western culture was setting a bad example for the strictly controlled mainland spurred the government to gradually tighten its grip on the island. (The greatest, nagging fear that the PRC nurtures--especially under the rule of current President Xi Jinping--is an uprising among the general population.) New laws were imposed limiting the freedoms of Hong Kong residents. Alleged violators now could be extradited to the mainland and tried under the PRC’s much more stringent legal code and subjected to harsh punishments, often life sentences in “re-education” camps. The crackdown was immediately challenged by Hong Kong residents, especially young people who quickly organized mass demonstrations that have been met by increasingly more violent reactions from the mainland-supported police.

Always in the background has lurked the specter of the home government sending in detachments of the People’s Liberation Army to quell the unrest, as it did during the 1989 Tiananmen Square demonstrations and subsequent massacre in which hundreds of Chinese citizens lost their lives.

How this will eventually shake out remains to be seen, but in the meantime, operators with business interests in Hong Kong should monitor the situation closely as it continues to develop. It should be noted that even the COVID pandemic has failed to damp down the dedication and enthusiasm of the demonstrators.

If it is essential to go into Hong Kong’s Chek Lap Kok International Airport for a passenger repatriation, a medical drop or pickup, or simply to conduct business, it is still possible. Of course, the usual cyber-chase for permits, visas, slots, parking, etc., to get into this highly congested airdrome will still be necessary--only now made even more bureaucratic to accommodate COVID-19 concerns.

In Bangkok, Julie Ambrose, director of aviation at ASA Group, reports that her employer has worked “a number of flights in and out of Hong Kong, particularly medical flights. For once, there are no parking issues in Hong Kong. They have updated the requirements the most of any destination in the region in terms of who can come in and other issues.” Sometimes it seems these requirements change from hour to hour, so the international operator’s mantra continues to apply: Check early and often for the latest updates.

“Hong Kong is still one of the top business aviation destinations due to its status as an international financial hub,” the AsBAA’s Chiang added. “There are no reasons to be concerned about flying in there. It is still a safe place - if you abide by the local laws. It is a major metropolis like others in the world and should be approached that way. Parking today is still tight but slightly better than pre-COVID because so many of the airliners have been moved overseas for storage.”