Flying Circling Approaches In The Real World, Part 2

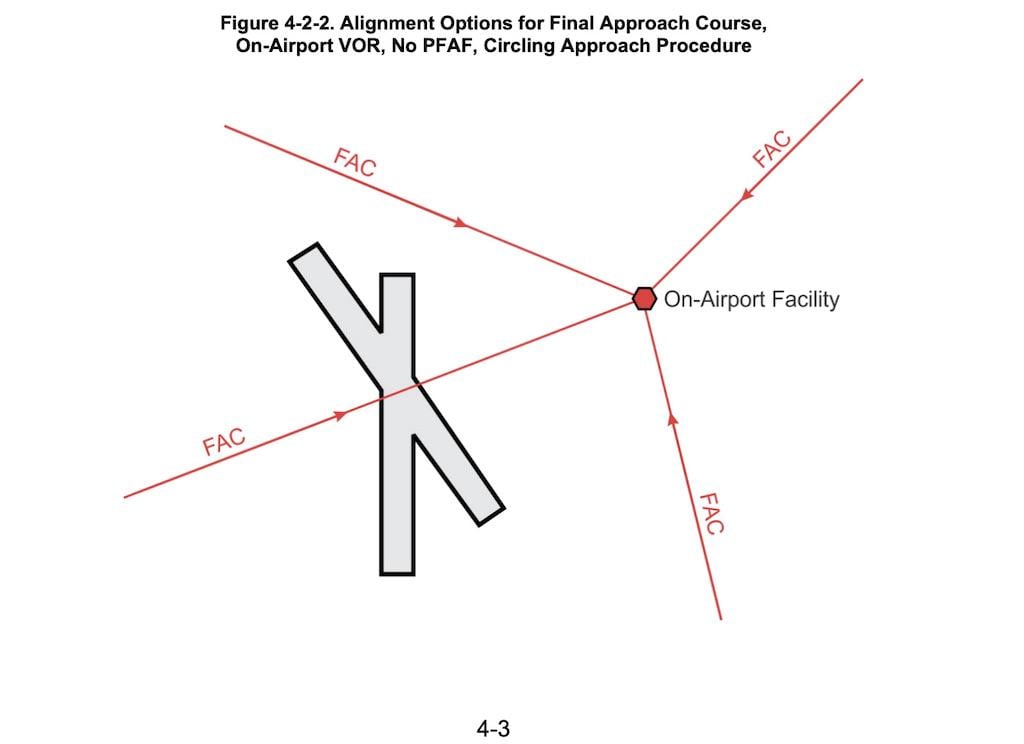

Illustration from U.S. Standard for Terminal Instrument Procedures (TERPS)

In Part 1, we discussed how there’s a significant difference between flying a circling approach in training and flying one in the real world.

In the U.S., approaches are created using criteria contained in FAA Order 8260.3E, “U.S. Standard for Terminal Instrument Procedures (TERPS).” These same approach criteria are used in Canada, Korea, Saudi Arabia, Taiwan and at some NATO military installations.

Most other parts of the world, however, create instrument approaches using International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) procedures found in Doc. 8168, “Procedures for Air Navigation Services—Aircraft Operations (PANS-OPS),” that essentially translate into larger areas of protected airspace. But some of those differences remain in flux.

For example, indicated airspeeds (IAS) applied under TERPS differ from the speeds used under PANS-OPS. In the U.S., the IAS for Category A aircraft is 91 kt. or less. Using PANS-OPS, that speed increases slightly to 100 kt. As aircraft increase in size, those speeds grow further and further apart. Consider Category C aircraft where the speeds are 121 kt., but less than 141 kt. Under PANS-OPS that speed increases to 180 kt.

The turn radius applied in a circling approach under TERPS has increased over the years to more closely align with PANS-OPS. A Category C aircraft circling at sea level today must remain within 2.7 nm of the landing runway threshold. But not all TERPS approaches have been updated. Approaches that include the updated turning radius are denoted by a black square with a letter “C” inside.

Obstruction clearance under TERPS is less than that at many international airports, just 300 ft. across all categories. PANS-OPS offers obstruction clearance beginning at 295 ft. and increasing to nearly 500 ft. for the largest aircraft. The minimum visibilities available to pilots at the obstacle clearance altitude are also considerably larger under PANS-OPS. For a Category A aircraft, the visibility is 1 mi. (1.6 km) under TERPS and 6,234 ft. (1.9 km) under PANS-OPS. Again, as aircraft increase in size, Category C visibilities under TERPS are 1.5 mi. (2.4 km) while under PANS-OPS that distance grows to 2.3 mi. (3.7 km).

Real-World Comments

Several online discussions with business aviation pilots about circling approaches revealed some of the operational issues.

Comments seen more than once include, “Circling in IFR weather is rare and oftentimes considered an abnormal event.” A few pilots said their company minimums for a circling approach were basic VFR, or a 1,000-ft. ceiling and 3-mi. visibility. A Gulfstream G650 pilot agreed with the basic VFR weather minimum to circle and added, “It must be 1,500 and five at night for us to accept a circling approach.”

The operations manual at one company operating a Global 6000 says, “All circling approaches should be conducted using Category D weather minimums regardless of aircraft certification. Crews attempting a circling approach at night are prohibited from using this procedure in mountainous terrain or when the weather is less than basic VFR.” A Falcon 7X pilot highlighted an important aspect of the weather minimums discussions. “If you’re in VMC and not flying or transitioning from an instrument approach to a different runway, you’re technically not even flying a circling approach.” Most said they considered these approaches as visual circling maneuvers.

One pilot said, “The NTSB (March 2023 Safety Alert about circling approaches) tells me that we (also) need to train pilots to fly a VFR traffic pattern. The three accidents in the report were all MVFR (Marginal VFR) or better.” His company also considers a circling approach to be an abnormal procedure.

A Falcon 2000 pilot said, “We have used a lot of part-timers lately and it’s surprising when I watch how these pilots enter a traffic pattern or struggle to determine the appropriate pattern altitude. They just do not know what to do. I tell them to fly the airplane and look outside.” Another said, “The more pilots I fly with the more surprised I am at how many don’t remember how to join a regular traffic pattern. They often end up high or low and slow on base to final. If you can’t fly a basic pattern, you have no hope of flying a nice circling approach.” He added, “We have begun asking our 142 training provider to start giving us more realistic circling scenarios in recurrent.”

A Gulfstream captain countered that. “Circle to land training in the sim has little value IMHO to the real world. Like the LOC 27 MEM circle 18R. Hit the FAF, descend at 1,000 fpm to MDA, field in sight 25-deg. bank to 316 heading for 20 sec. then 26-deg. bank to heading 270. When runway at 10 o’clock position set 1.2 EPR descent at 500-fpm. Land. That’s about as artificial as can be.”

Flying Circling Approaches In The Real World, Part 1:

https://aviationweek.com/business-aviation/safety-ops-regulation/flying…