Virtual Reality Simulator Provides Realistic Training Scenarios, Part 1

The urban landscape patrolled by the LAPD’s Air Support Division is filled with an abundance of obstructions, including utility wires.

Most of us slept soundly last night, secure in knowing that the risk to our individual safety from a fire in our home or a home invasion by a criminal is thankfully low.

We teach our young children the value of dialing 911 when faced with an emergency, and in the U.S., depending on the severity of the report, legions of sirens from first responders will converge on the scene to protect our safety, health and security.

These selfless first responders will turn into a dark ally where armed criminals are hiding or rush into burning buildings while the rest of us would flee. If police officers are fortunate, they will have back up right behind them, and perhaps, even above them. Unfortunately, these public safety missions are performed in adverse environments with little to no margin for error.

Unforgiving Mission Environments

A fatal accident involving the Huntington Beach, California, Police Air Support Unit on the evening of Feb. 19, 2022 illustrates several of the considerable risk factors inherent to law enforcement aviation.

A large gathering of people erupted into a street fight on a waterfront peninsula. Multiple units responded, to include the department’s airborne MD-520N helicopter. The aircraft is equipped with a NOTAR-design tail rotor, which uses a variable thruster and ducted fan system for anti-torque control rather than a conventional tail rotor.

The pilot remembered orbiting about 500-600 ft. AGL when without warning, the helicopter yawed aggressively to the right. The pilot’s attempt to control the helicopter was hindered by the lack of horizon and no accurate external visual references. The number of people in the vicinity further complicated his options. The MD-520N impacted the adjacent water uncontrolled in a downward right rotation. The violence of the impact coupled with water visibility less than 20 in. complicated the rescue effort. The pilot was able to extricate himself from the tangled mess of the submerged wreckage, but unfortunately the tactical flight officer’s body was found trapped by the rescuers.

Post accident investigation using flight-track data and onboard imaging revealed that, after factoring the relative wind, the helicopter had essentially transitioned into a hover and was flying almost perpendicular to the direction of travel for 30 sec. before entering the rotation. The NTSB reported this was likely because the pilot was fixated on the scene as it became obscured by buildings, and he was concerned about the safety of ground patrol officers who had just arrived.

The NTSB determined the cause of the fatal accident to be the helicopter’s encounter with unanticipated right yaw during a low-altitude, low-airspeed, tight-radius orbit. Contributing to the accident was the pilot’s distraction during the orbit, which resulted in the loss of control, fatigue due to his early wake time, and lack of external cures that hindered his ability to perform a recovery.

Challenges of Law Enforcement Aviation

Kevin Gallagher, chief pilot of the Los Angeles Police Department Air Support Division, oversees the pilots and tactical flight officers (TFO) who take off 24/7 into the crowded skies over the LA metroplex to safeguard its citizens and the patrol officers on its streets. Their mission is filled with an abundance of environmental and mission factors that greatly elevate the challenges far beyond “standard” aviation.

Given these complexities it is standard for a law enforcement helicopter to have a two-person crew. The key goal for the pilot is to put the aircraft in the best possible position to help the officers on the ground while coordinating closely with the TFO in the other seat who is working directly with the dispatchers and ground units.

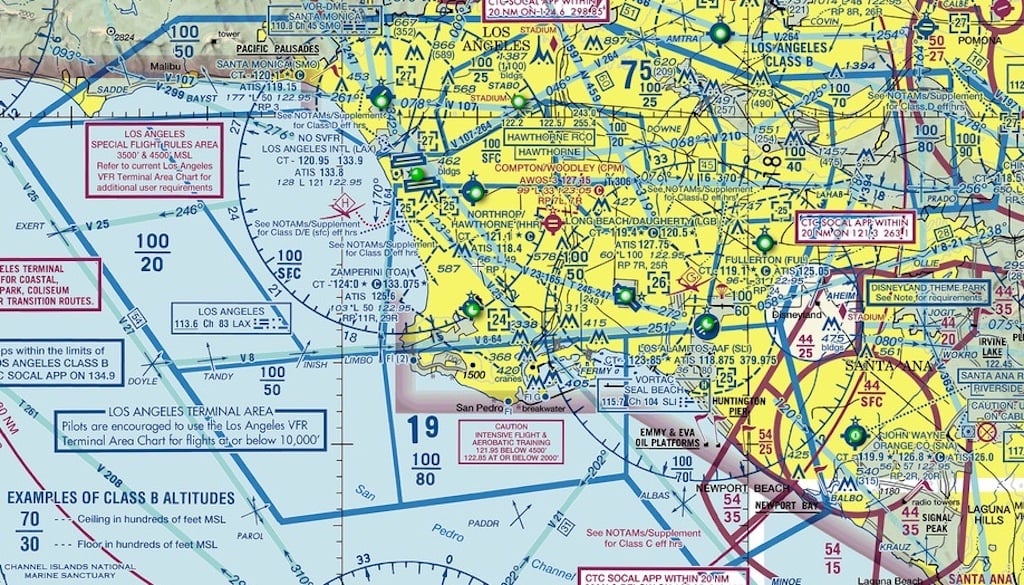

The TFO can be working as many as five separate police radio frequencies. Simultaneously, the pilot may be using two separate aviation radios for communicating with air traffic control and monitoring the common traffic advisory frequency in the Los Angeles Basin.

Gallagher places a premium on crew resource management (CRM). Even though the duties are formally divided, a good law enforcement pilot will anticipate what the TFO and the ground units need.

An incident can rapidly evolve, requiring dynamic communications and decision making. For example, a suspect hopping into a vehicle and speeding away can quickly involve a fast-moving coordination with multiple police jurisdictions while the pilot rapidly coordinates with air traffic controllers transiting through Class B, C and D airspaces. Now consider this scenario if the fog layer from the coastline begins to flow inland, which is a meteorological condition that frequently occurs along the Los Angeles coastal communities, quickly dropping the visibility from good VFR to low IFR minimums.

The NTSB’s investigation report of the fatal accident at Huntington Beach highlights the instinctive involvement of the pilot to become fixated on the situation on the ground. This can negatively affect the pilot’s situational awareness. The typical flight profile over an incident can expose a helicopter to wind from an adverse azimuth thereby making it susceptible to a Loss of tail rotor effectiveness incident. The low speed orbiting can also put a helicopter within the envelope for vortex ring state of the main rotor.

It isn’t uncommon for a law enforcement helicopter to be orbiting at 500 ft. and 60 KIAS. If an engine fails, the crew has precious little time to react. Furthermore, the helicopter is likely flying over a densely populated area with few spots for an autorotation landing. At best, the pilot might have a street intersection or center turn lane that hopefully is vacant of traffic. These can be covered by an abundance of utility wires, creating a further impediment to a safe landing.

“If something happens with the aircraft they have to make the right choices immediately to avoid a dire outcome,” says Gallagher. “That requires a strong level of proficiency and judgment. Training is how we help them maintain their high skill levels.”

The LAPD Air Support Division recently announced its intent to purchase a virtual reality flight simulator, in Part 2 of this article.