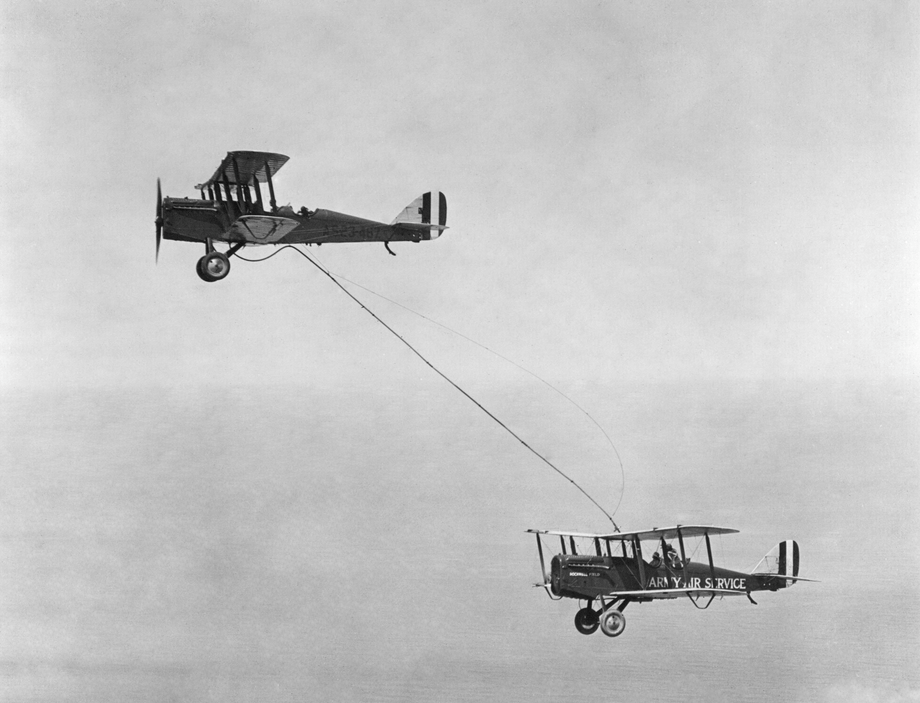

The first aerial refueling took place on June 27, 1923, above Rockwell Field in San Diego, when two U.S. Army Air Service Airco DH-4s demonstrated that the concept would work in practice. The tanker extended a 50-ft. rubber hose from the rear cockpit, which was grabbed by the crew of the receiving airplane. Around 75 gal. of fuel was passed between the two aircraft, and only the single contact was made before an engine issue curtailed the demonstration.

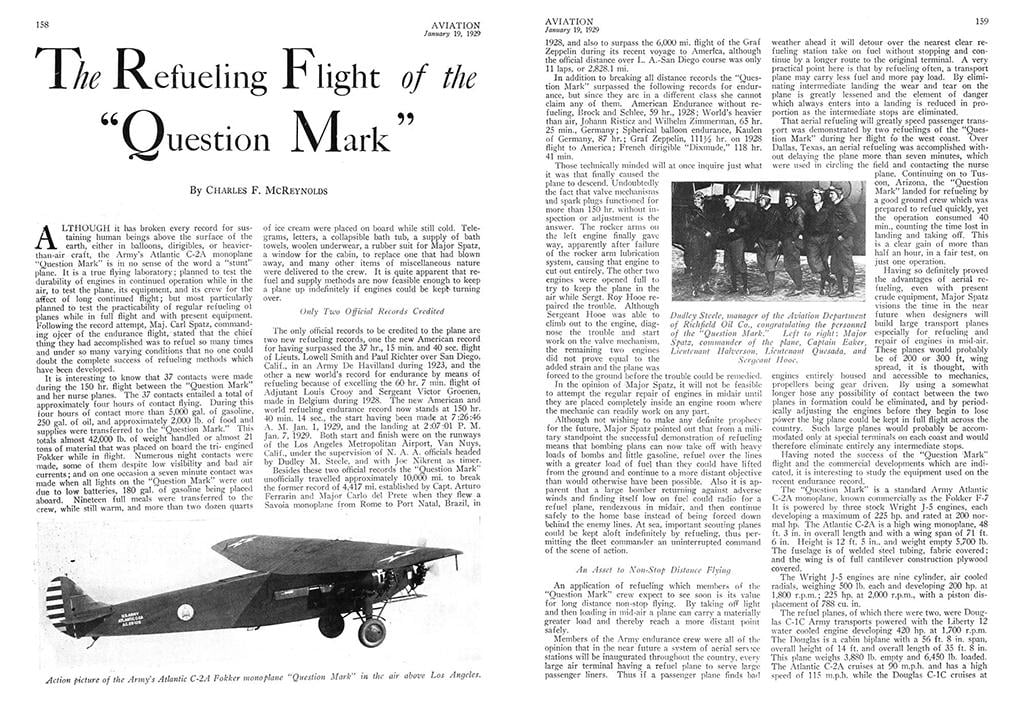

A compelling practical reason to carry out aerial refueling was slow to emerge, and early demonstrations became little more than record-setting attempts. On Jan. 1, 1929, a six-man crew commanded by U.S. Army Air Corps Maj. Carl Spaatz took off in a modified Fokker C-2A called Question Mark. The airplane bore the symbol as the team’s answer to the question: “How long do you plan to stay up?” On Jan. 7, the answer proved to be 150 hr. 40 min. Aviation magazine ran five pages on the flight.

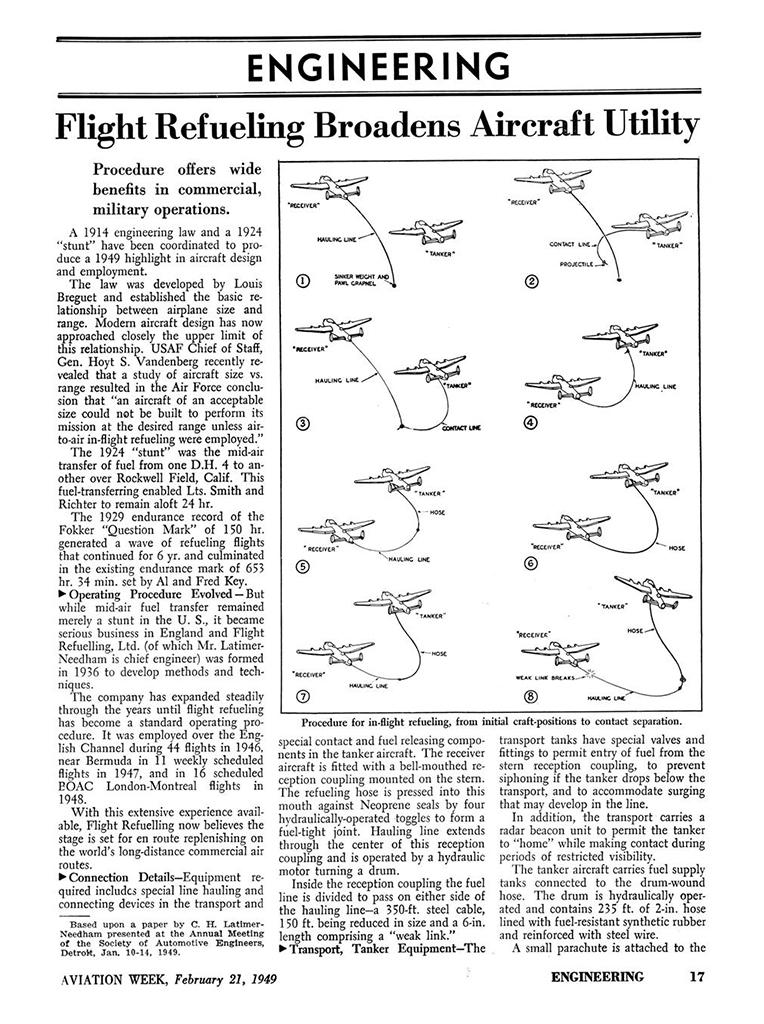

Alan Cobham, the British pioneer of long-distance flying, spent much of the 1930s developing systems intended to permit long-distance nonstop commercial flights. He would go on to establish Flight Refueling Ltd. (FRL) as a company in 1934. His early experiments were conducted using the Airspeed AS.5 Courier, before he developed the “looped-hose” gravity-feed method in the mid-1930s and created a system of connectors that increased safety and made refueling a more easily repeatable process. In a February 1949 edition, Aviation Week published a diagrammatic explanation of FRL’s operational concept.

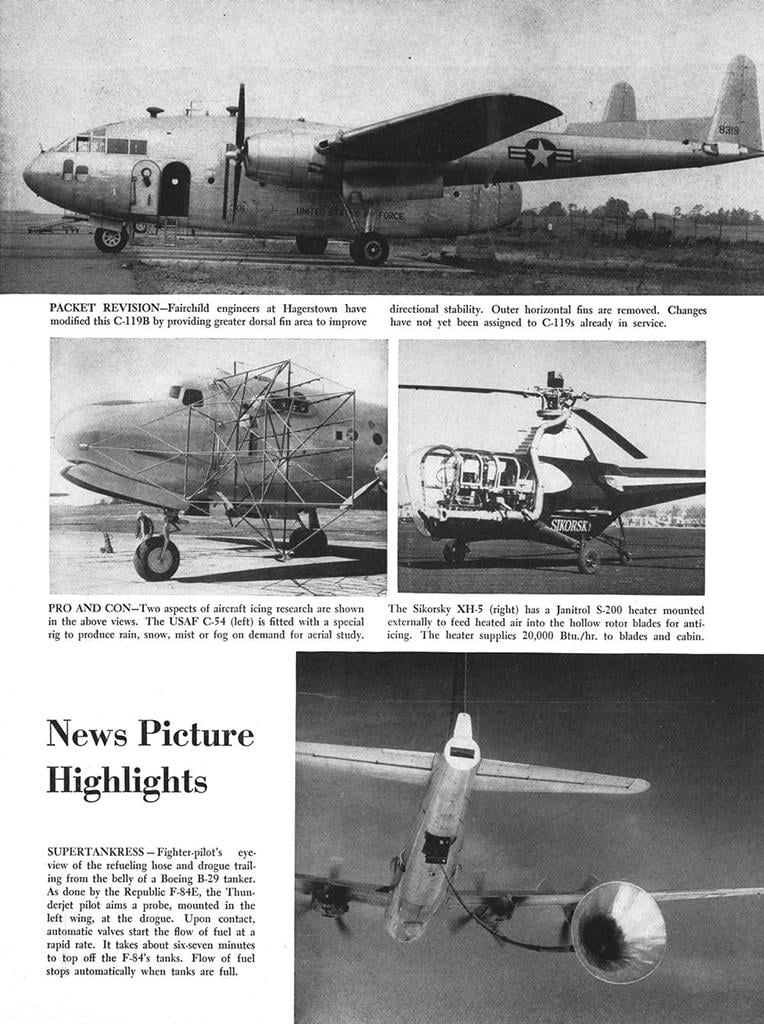

After a UK Royal Air Force program to modify Avro Lancaster bombers to use as tankers for a long-range strike on Japan was canceled when World War II ended, Cobham’s Flight Refueling Ltd. signed a contract to deliver more than 40 refueling kits and technical support to the U.S. Air Force. Dozens of Boeing B-29s were modified to become tankers, and the U.S. Air Force stood up its first aerial refueling squadrons.

Between Feb. 26 and March 3, 1949, a Boeing B-50 Stratofortress known as “Lucky Lady II” completed a 94 hr. 1 min. nonstop, round-the-world flight. It was refueled four times—over the Azores, West Africa, near the Pacific island of Guam, and between Hawaii and the U.S. West Coast—by pairs of Boeing KB-29M tankers. Prior to this unprecedented flight, the crew had only performed one midair refueling.

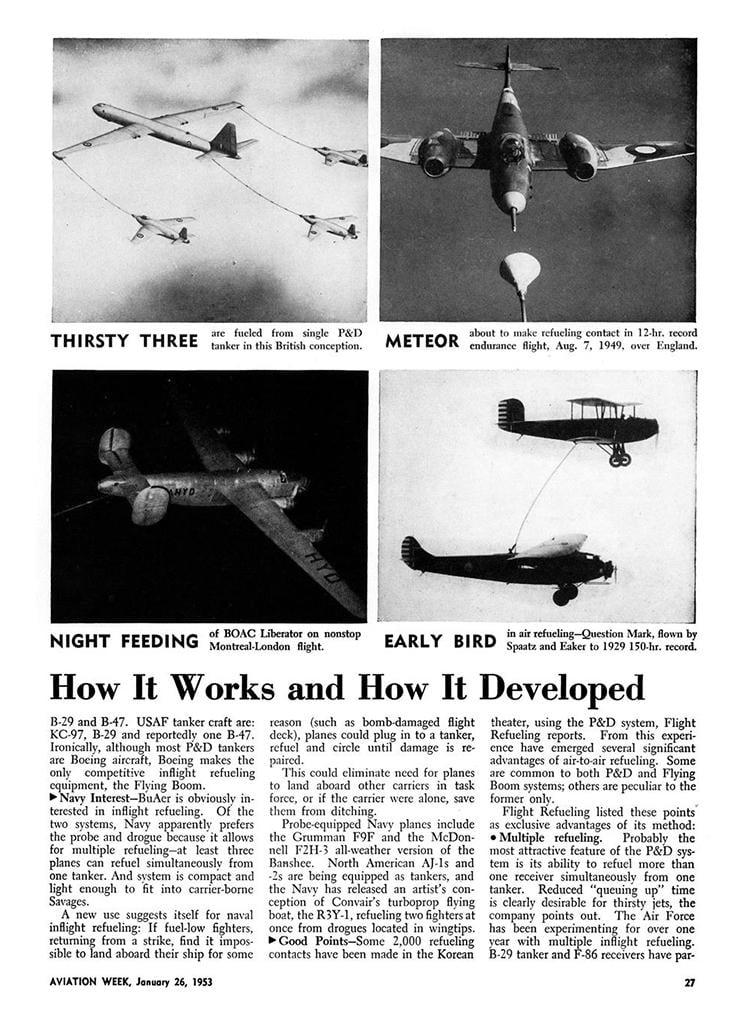

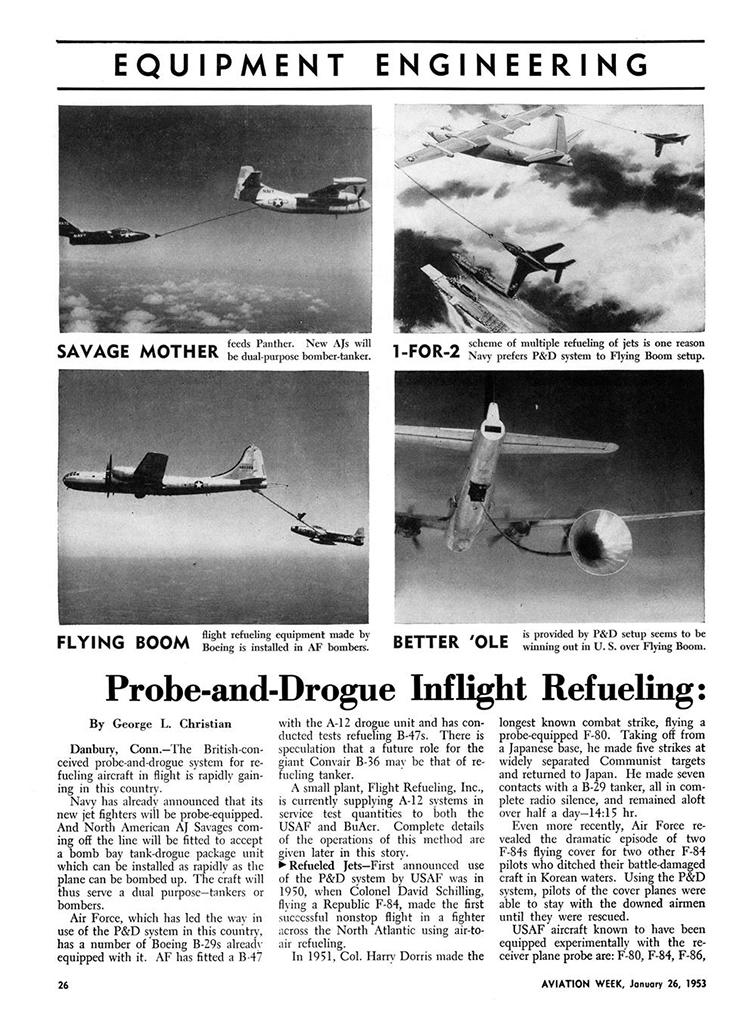

Cobham developed a new system, which went into trials with the Royal Air Force, and on Aug. 7, 1949, was used during the setting of a new endurance record for a jet aircraft when a Meteor F.3 was refueled from an Avro Lancaster. The connectors used in the new “probe and drogue” system remain the basis of the NATO standard still in use today.

FRL’s refueling equipment was modified by Boeing for the U.S. Strategic Air Command, which saw the flexible hose replaced by a boom with rudders that could be “flown” by the operator. Initially developed to permit refueling at altitude, with operators in pressurized cabins, the system also increased the fuel transfer rate. It was used on the Boeing KC-97 Stratofreighter, the first production tanker aircraft, and the concept remains in use by the U.S. Air Force and the air forces of Australia, Iran, Israel, the Netherlands and Turkey.

It cannot really be called aerial refueling—the tanker was a truck, with the receiving aircraft flying a few feet above it on a long, straight stretch of desert highway—but the endurance record set by this Cessna 172 will surely never be broken. In a stunt to promote the Hacienda Hotel in Las Vegas, former bomber pilot Robert Timm and mechanic John Wayne Cook took off on Dec. 4, 1958, and did not return to the ground until Feb. 7 the following year. Food and water was hauled up from the truck; they bathed on a platform beside the fuselage. The airplane, lost for years, was found in Canada and brought back to Sin City in the 1990s. It now hangs above the baggage carousels at McCarran International Airport.

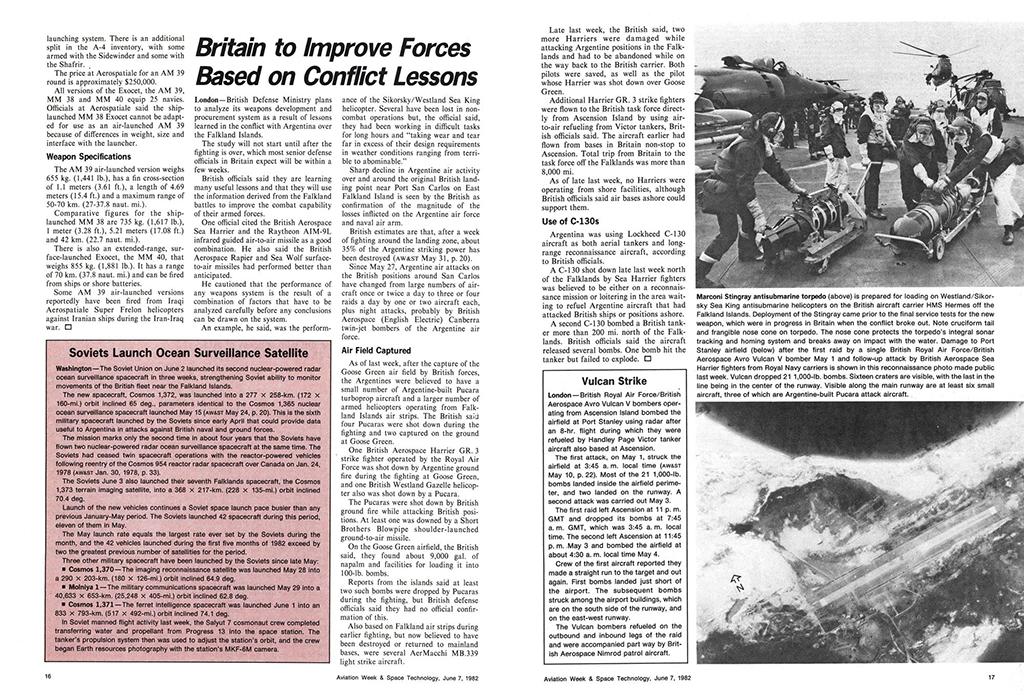

The first midair refueling during combat took place in 1951 off the coast of Wonsan, Korea. But surely the most elaborate were the series of missions known as Operation Black Buck: An operation conceived and carried out by the Royal Air Force during the Falklands War of 1982, when 12 Handley Page Victor K2 tankers executed an interlinked chain of air-to-air tankings and buddy refuelings to enable one Avro Vulcan B2 to reach the runway at Port Stanley airfield and drop bombs to deny its use to the Argentines.

Aerial refueling was key to what remains the longest-range bombing mission ever accomplished. Between Oct. 6-11, 2001, pairs of Northrop Grumman B-2 Spirit stealth bombers took off from their home base of Whiteman, Missouri, and headed west. In an account published in 2014 by Mel Deaile, who flew in Spirit of America on the second night, the aircraft refueled over California, near Hawaii, over Guam, above the Malacca Straits, and near Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean, before spending 2 hr. dropping 12 of its 16 Joint Direct Attack Munitions over Afghanistan. After another refueling, they were asked to return to release the remaining four weapons. Then the crew met with a tanker for a final time before landing on Diego Garcia, a little under 44.5 hr. after leaving Whiteman.

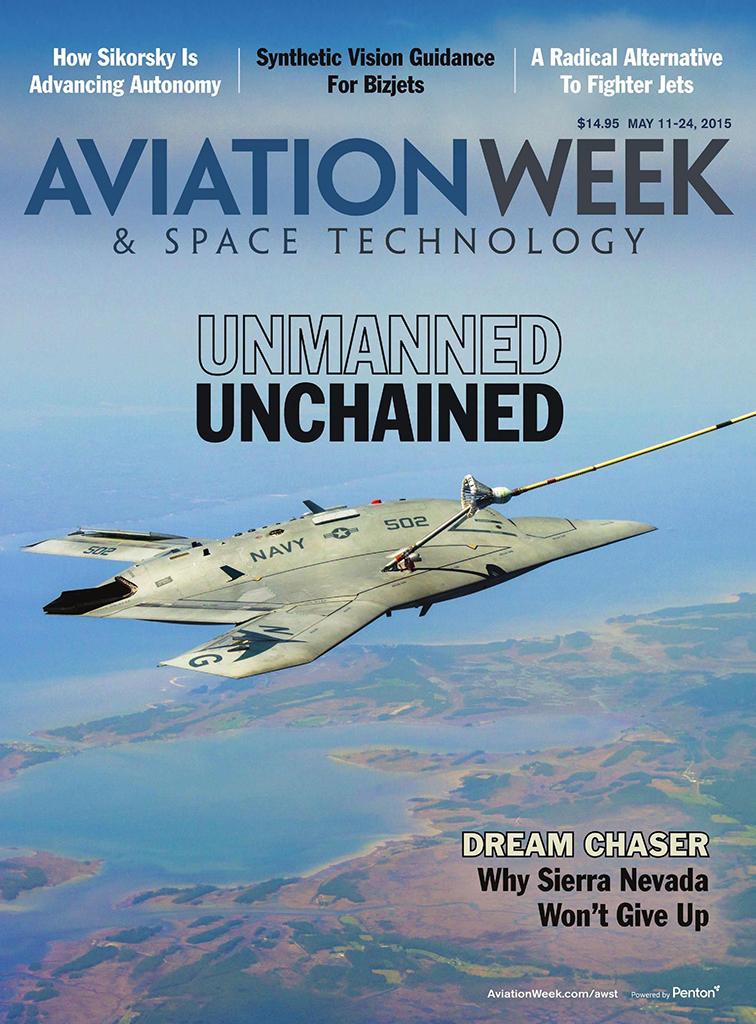

The Northrop Grumman B-2’s subscale, unmanned cousin, the X-47B, carried out the first autonomous refueling in flight in the spring of 2015. Aviation Week marked the achievement with a cover story on the program.

In the mid-2010s, an EU-funded study looked at the potential utility, feasibility and commercial desirability of midair refueling for commercial flights. The program—Research on a Cruiser-Enabled Air Transport Environment (Recreate)—claimed that air-to-air refueling could help airlines achieve operating cost reductions of around 12%. The researchers also maintained that such operations, particularly when performed autonomously, could be carried out safely and with minimal training burden.

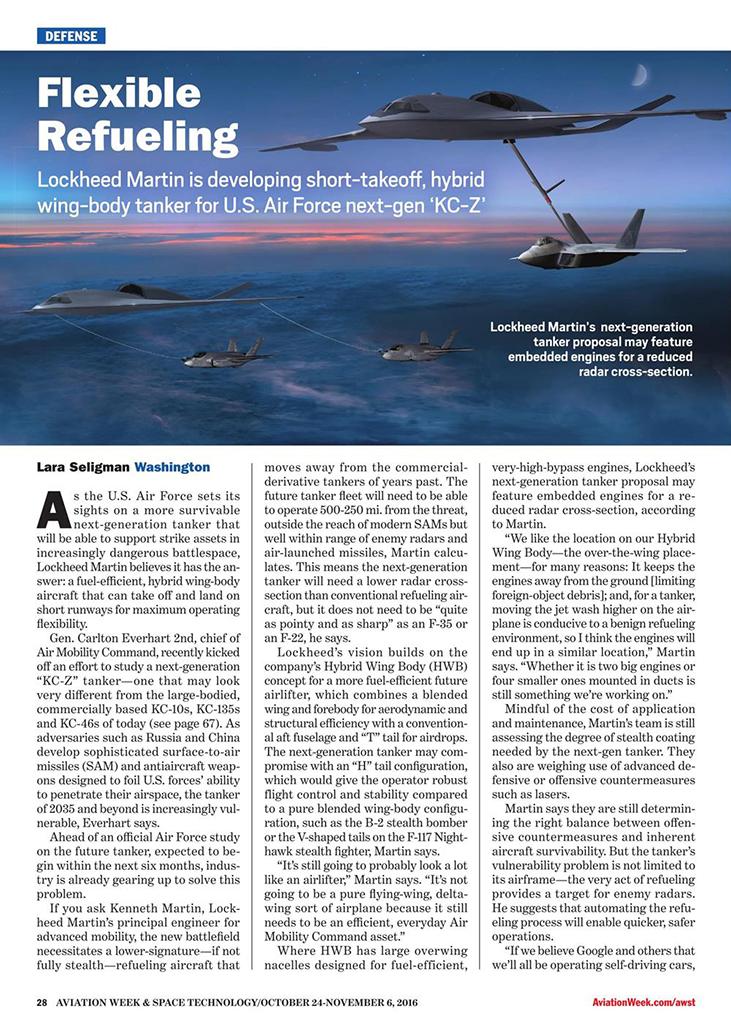

With the Lockheed Martin F-35 bringing stealth technology into a growing number of countries’ fleets, the operational and business cases to support development of low-observable tankers are building steadily. Lockheed Martin’s next-generation tanker concept, as revealed in the Oct. 24, 2016, edition of Aviation Week, points toward one possible shape for the future as aerial refueling nears its second century.

Refueling an aircraft in flight is a practice with a history almost as long as that of powered flight itself. Although today the technology and the operational processes are the exclusive preserve of military aviation, the first practical uses for midair refueling were in commercial and cargo roles. And many of the milestones achieved of refueling history were chalked up during attempts to set airborne endurance records.

The move from primarily wooden airplanes to metal airframes as well as the development of more efficient and capable engines dramatically increased performance, thereby reducing the need to refuel in the Interwar years. But the new political realities of the Cold War—and the emerging military requirement to hold targets at risk over huge distances—made air-to-air refueling a vital part of modern military aviation operations. There are some, too, who believe it still has a role to play in the evolution of commercial aviation.

Comments

Bernard Biales