100 Top Technologies: 'Tipping the Wing' to 'Printing the Future'

Guy Norris Graham Warwick May 12, 2016

76. Winglets

The drag-reducing winglet is another aerodynamic improvement now widespread across airliner fleets. It reduces vortex-induced drag by diffusing the tip vortex flow downstream of the wingtip and increases lift at the wingtip by inhibiting the flow of higher-pressure air below the wing to lower-pressure air above. Developed initially in response to the 1973 oil crisis, NASA flight tested a Whitcomb-designed winglet on a Boeing KC-135 in 1979. In 1988, a similar-looking feature debuted on the Boeing 747-400. Airbus, meanwhile, adopted a lower-profile, end-plate wingtip device that projected above and below the end of the wing. The shape was first introduced on the A310-300 and A320 and in a much larger form, on the A380. McDonnell Douglas also tested a form of bifurcated winglet on a DC-10 in 1981 and introduced a 7-ft.-tall upper winglet with lower vane on the MD-11 in 1990. Larger elliptical or blended winglets are now commonplace on Airbus and Boeing aircraft, though all-new wing designs on the 787, 747-8, 777 and 777X feature raked tips.

77. Relaxed Stability

Development of stability augmentation systems and later fly-by-wire (FBW) flight controls allowed the inherent stability of aircraft to be reduced, or relaxed, to improve performance. The FBW F-16, first flown in 1974, has relaxed longitudinal static stability to increase agility. Flown in 1981, the aerodynamically unstable F-117 was made flyable by FBW. The McDonnell Douglas MD-11 airliner introduced in 1990 had relaxed longitudinal stability, allowing for a smaller horizontal tail to reduce fuel burn.

78. Night-Flying Aids

Nearly 70 years of operational experience and improvement have led to near-ubiquitous use of night-vision goggles (NVG) in the military and increasing use in the more challenging general aviation and public sectors, including police and emergency medical services. Generation Zero (Gen 0) hand-held night scopes emerged in the 1950s, evolving into the forward-looking infrared (FLIR) systems that were later mounted on military aircraft, paving the way for the Low-Altitude Navigation Targeting Infrared for Night (Lantirn) system later used on attack aircraft for air-to-surface missiles.

The Army was the first U.S. military service to use NVGs in aviation, starting with helicopter pilots in Vietnam. It would be decades before the Air Force began using the devices in combat. Aviation Week reported in the April 1, 1996, issue that A-10 pilots equipped with NVGs had just begun conducting night operations over Bosnia “after verifying new close air support tactics at a Red Flag exercise.” The 81st Fighter Sqdn., to which the A-10s belonged, was the first active duty fighter squadron to operationally employ NVGs. The Air Force first rolled out the devices in its National Guard units in the early 1990s in a drug interdiction role.

Aviation Week reported in its Oct. 28, 2013, issue that the military was looking at digital-image intensifiers that can work with less light and zoom, record and transmit the video.

79. Delta Wing

During World War II, delta wings for high-speed flight were studied by Alexander Lippisch in Germany; post-war, Britain used similar thick delta wings for the subsonic Avro Vulcan bomber and Gloster Javelin fighter. Concurrently, during the war, the U.S. National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) aerodynamicist Robert T. Jones developed the thin delta wing for low-drag supersonic flight. The wing design was used by Convair in the XF-92 in 1948, which led to the U.S. Air Force’s F-102 interceptor in 1953 and B-58 bomber in 1960. Dassault also used the design in the Mirage III in 1956. Sweden’s Saab pioneered the now-popular close-coupled delta-canard configuration with the Viggen fighter in 1967. The Aerospatiale/BAC Concorde supersonic airliner entered service in 1976 with a slender delta, or ogive, wing first tested on the BAC 221 in 1964, but Russia’s rival Tu-144 was redesigned with a double-delta wing and retractable foreplanes.

80. Autoland Systems

One of Aviation Week’s earliest mentions of autoland technologies occurred in 1962, following the FAA’s evaluation of the British autoland system on a specially equipped Douglas DC-7. The four-engine propeller transport had conducted 310 “completely automatic” landings with the Blind Landing Experimental Unit (BLEU) in Bedford, England. The British developed the autoland system primarily for bombers and civil transports, including the Armstrong Whitworth Argosy 660, Hawker Siddeley Trident and Short Belfast. The systems were soon to be used in airline operations with Hawker Siddeley and other early frontrunners, including the BAC One-Eleven (BAC-111) in 1963 and Sud Aviation Caravelle in 1964, offering autoland as an option. Staff writer Herbert J. Coleman evaluated the Trident autoland system in a pilot report on “blind landings” at Heathrow Airport in the Dec. 12, 1966, edition.

81. Tiltrotor

The Transcendental 1-G was the first tiltrotor to fly, in the U.S. in 1954, but it was the Bell XV-3 in 1955 and the XV-15 in 1977 that proved the soundness of the VTOL design. This led to the Bell Boeing V-22 tiltrotor transport, which first flew in 1989 and entered service with the U.S. Marine Corps in 2007 after surviving near-cancelation. Originally developed by Bell, the Leonardo AW609 (pictured) is the first civil tiltrotor; certification is set for 2017.

82. EFBs with Moving Maps

With the introduction of the iPad in 2010, static paper charts began taking a backseat to the real-time data revolution in general aviation aircraft. With burgeoning software applications for the iPad—and tablets, iPad minis or even smartphones—companies such as Garmin and Foreflight—had created a new reality for general aviation pilots: low-cost options for not only flight planning, but glass cockpit displays, real-time aircraft position, terrain, synthetic vision, weather and traffic updates from FAA feeds, geo-referenced approach charts and airport maps. And all for a couple hundred dollars a year for updates.

83. Instrument Landing System

84. Advances in Pilot Controls

Side-stick controllers, introduced for airliners in the late 1980s in combination with fly-by-wire control for the Airbus A320 family, are now found in cockpits of virtually all manufacturers with the exception of Boeing. Human factors concerns, not technology, guided the early design work on side sticks. In the Sept. 3, 1984, Aviation Week, writers described how Airbus had added side-stick controllers to an A300 test aircraft, leaving the right-side control yoke in place. With side sticks, the inputs from one pilot for the first time would not be replicated in the side stick of the other pilot, as was the case with mechanically linked control yokes in the past, and Airbus wanted to determine how to handle cases where pilots make contradictory control inputs at the same time. Newer aircraft, including Gulfstream’s G500 and G600 business jets, have active feedback between the side sticks.

85. Articulated Rotor

A breakthrough rotorcraft design, the fully articulated rotor was developed by Juan de la Cierva for the autogyro. Each blade was attached to the hub via hinges that allowed it to flap upward and downward as the rotor rotated to offset the difference in lift on the advanced and retreating sides in forward flight.

86. Rigid Rotor

Rigid rotors are hingeless. The blades are attached to a flexible hub and provide higher control power than an articulated rotor. Lockheed developed rigid rotors for the XH-51 in 1962 and the U.S. Army’s AH-56 Cheyenne, which was canceled in 1972. MBB in 1970 developed a rigid rotor for the Bo105 (pictured).

87. Fenestron

The fan-in-fin anti-torque system was patented in the U.K. in 1943 but made famous by Aerospatiale (now Airbus Helicopters) as the fenestron—first used in 1968 on the SA341 Gazelle.

88. Notar

Developed by Hughes Helicopters as an anti-torque control device for rotorcraft, the Notar uses a variable-pitch fan to drive air down the tail boom. Some of the air is expelled via two slots that run longitudinally down the starboard side of the boom to generate a boundary-layer control—the Coanda effect. The resulting flow produces up to 60% of the anti-torque needed in hover; a rotating direct jet thruster mounted at the boom’s tip provides directional control.

89. Fadec

Modern powerplants are started, efficiently operated and electronically monitored by a Full Authority Digital Engine Control (Fadec). The Fadec uses digitized input on air density, engine lever position, engine pressures, temperatures and other parameters to compute and manipulate fuel flows, stator positions and bleed valves.

90. Supercritical Airfoil

While early jet airliners relied on wing designs with conventional cross-sections, aerodynamicists including Richard Whitcomb at NASA Langley and Dietrich Kuchemann at RAE Farnborough realized more performance could be gained by tailoring the airfoil for transonic conditions. The focus was to delay the onset of the supersonic shockwave over the wing which causes wave drag, thereby allowing more efficient cruise performance at a higher Mach number. The resulting airfoil cross-sections were much flatter on the upper surface, blunter at the nose and inversely cambered at the lower aft wing surface. The flatter upper surface helped maintain a smoother boundary layer, while the blunt leading edge attenuated the suction peak; the scooped-out lower aft surface gave aft loading to generate increased lift. The overall outcome was that the shockwave moved further aft over the wing and reduced in intensity.

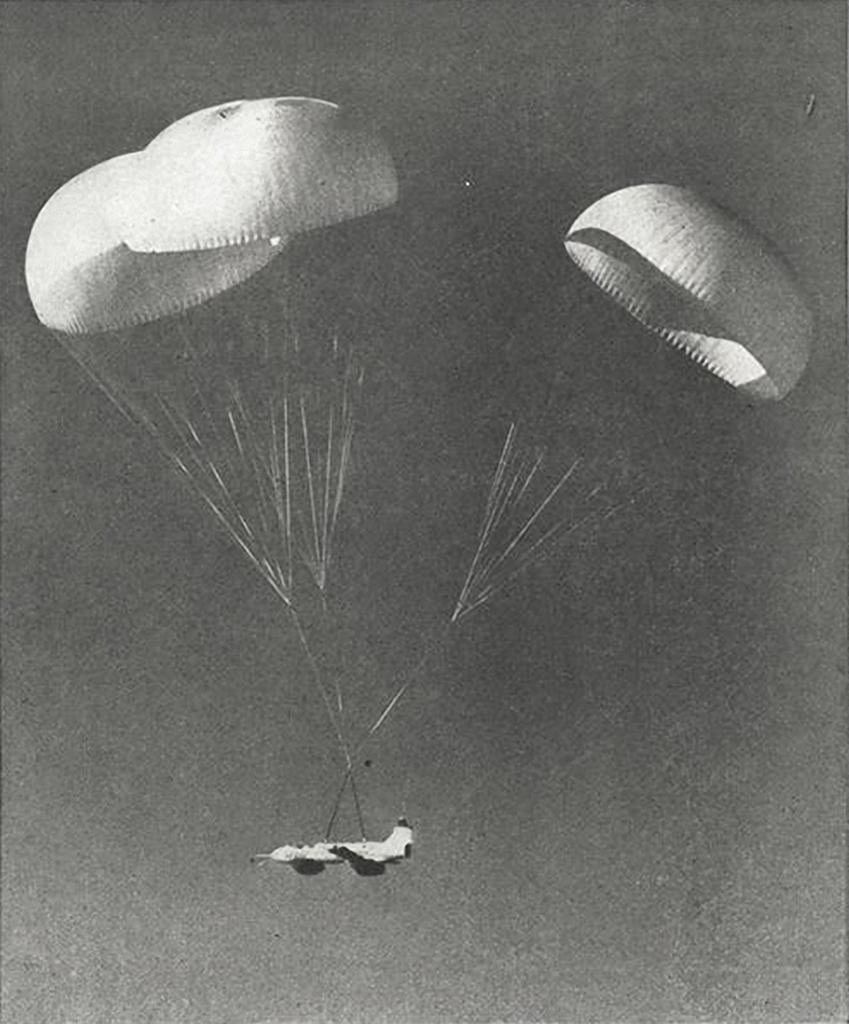

91. Airframe Recovery Parachute

Airframe parachutes gained widespread notoriety post-2000 with the introduction of the Cirrus Airframe Parachute System (CAPS) on the Cirrus SR20/22 line of single-engine piston-powered aircraft. Cirrus is currently in the process of completing its largest parachute to date, a CAPS that is three times as large as the SR22 parachute for its SF50 single-engine jet. CAPS, which uses a rocket (in combination with an airbag for the SF50) to launch a parachute that connects to the fuselage, is credited with saving 129 lives as of late March 2016. Earlier pathfinders include the Ballistic Recovery Systems (BRS) whole airframe systems for the ultralight sector, as well as some smaller general aviation models. The military also earns some credit for early adoption. Aviation Week’s Dec. 23, 1957, issue shows a live test of a whole airframe recovery system for the MGM-1 Matador surface-to-surface cruise missile. The system used three parachutes and airframe airbags to recover the vehicle without damage.

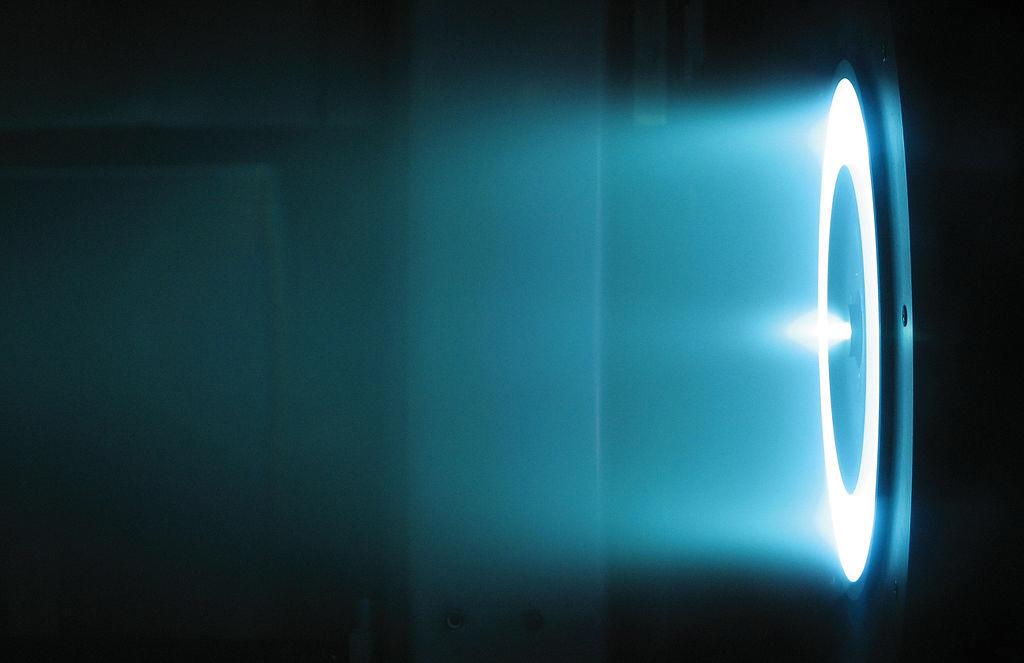

92. Electric Thrusters

As in Aesop’s fable of the tortoise and the hare, the principle behind electric space propulsion is “slow and steady wins the race.” These methods produce thrust much weaker than that from chemical rockets, but they are much more efficient. Work on the techniques in the U.S. and Russia dates to the 1950s.

The most common form of electric propulsion entails ionizing a propellant such as xenon to produce a plasma that generates thrust. Today, ion thrusters are in use on more than 100 Earth-orbiting satellites. And planners of deep-space missions see electric propulsion as one way to gradually reach high velocities to the outer reaches of the Solar System.

93. Thermal Protection

Spacecraft returning to Earth need a way to survive the vibration and heat of reentry. The extreme heat was by far the tougher problem facing the engineers and designers of space vehicles.

One approach, described by Robert Goddard, the liquid rocket engine pioneer, was to provide the spacecraft a shield coated with a thick surface that could gradually burn away. Such an ablative heat shield was used on manned spacecraft designs until the advent of the U.S. space shuttle.

Because it was to be reusable, the shuttle needed a new thermal protection strategy. Engineers came up with a variety of materials to use on different parts of the spaceplane’s body, depending on how much heat each area had to endure during the fiery return to the planet. These materials included ceramic tiles, reinforced carbon-carbon and Nomex blankets.

Early in the shuttle program, there were problems with tiles falling off. Those issues were painstakingly resolved. In 2003, the orbiter Columbia was lost during reentry due to damage to a carbon-carbon leading edge that had been struck by foam insulation, which had broken off the shuttle external fuel tank during the launch days earlier.

94. Glass Cockpit

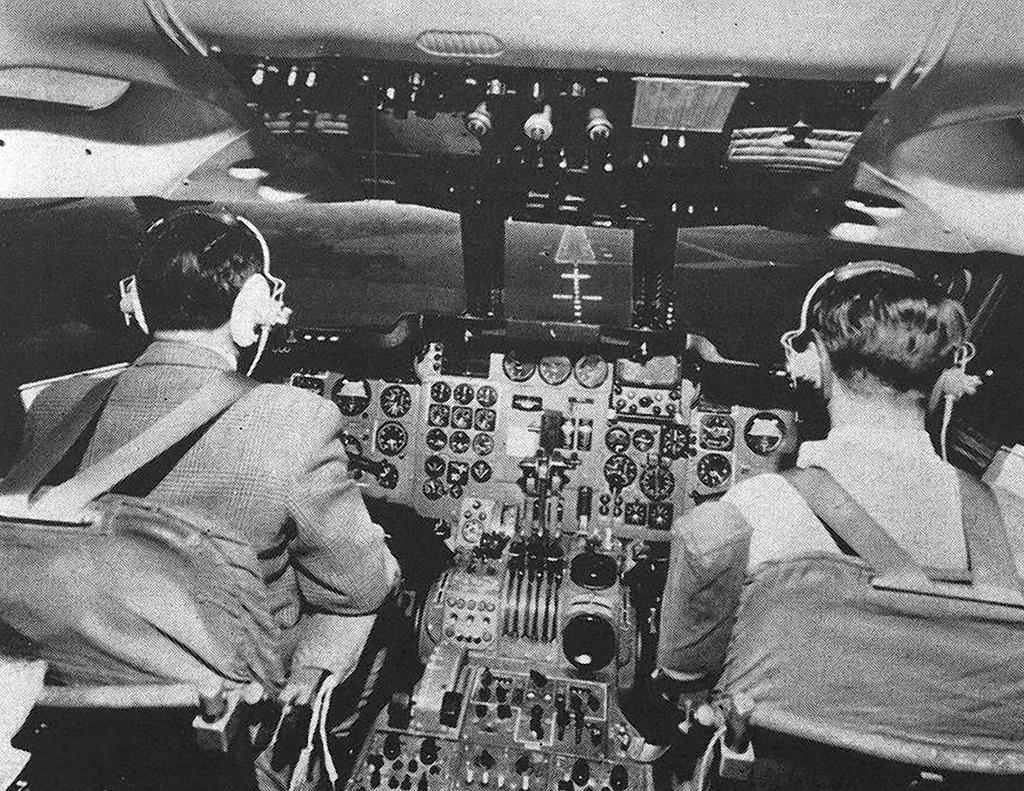

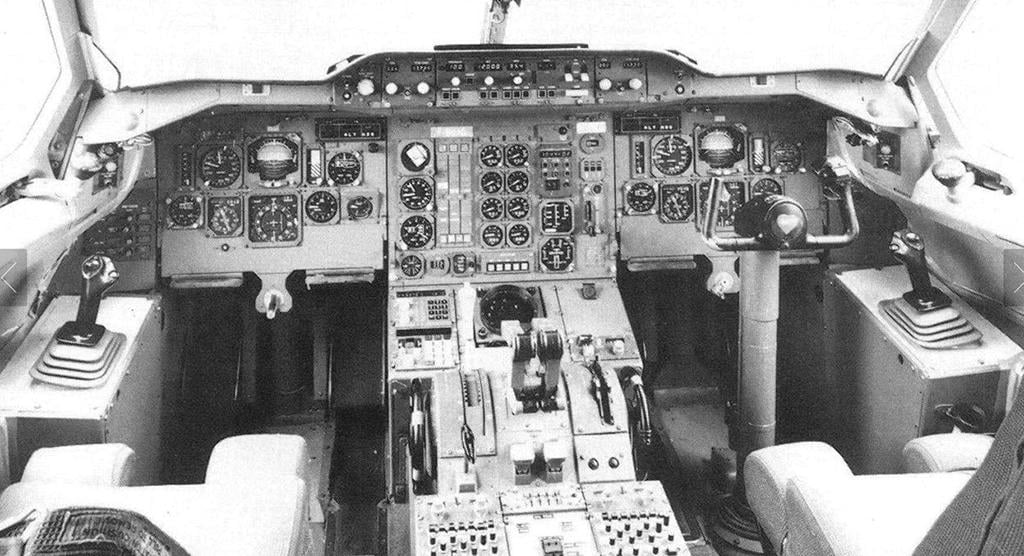

The beginning of the end for the third “man” in the cockpit—the flight-test engineer—came about in the early 1980s with the introduction of two-pilot flight decks for the Boeing 767 and 757 and a retrofitted Airbus A300.

While both the A300 and 767 were originally designed with a flight engineer station, the airframers each came to see the value in a two-person configuration and launched retrofit programs. Boeing’s began mid-stream in its 767 development program and Airbus’s in 1983, nearly 10 years after the A300 entered service. The 757 had been designed from scratch using a two-person flight-deck augmented with an engine-indicating-and-crew-alerting system (Eicas), a typical element of the modern integrated glass cockpit. Eicas provided engine operating status, cautions and warnings, aircraft status before takeoff, as well as noting discrepancies for ground maintenance.

“The first 767s were to be equipped with three-man cockpits,” Aviation Week reported in its June 7, 1982, issue, “but customers changed to the two-man configuration following a presidential commission’s decision that the aircraft did not need a third crewman.”

95. Spacecraft Stabilization/Attitude Control

To go beyond the mere ballistics of Sputnik, for flight into space to be useful beyond bombardment in warfare, a spacecraft needs to be stable in orbit. The first method is to set it spinning, like a gyroscope. Spin stabilization was used on early communications satellites and planetary probes; the technique is still in the spacecraft designer’s toolkit today. But three-axis stabilization offers even more potential. By using small thrusters, momentum wheels or control-moment gyroscopes, a spacecraft could keep pointed precisely without having to spin about one axis.

However, before a spacecraft can control its attitude it must be able to determine it. Over decades, engineers have devised and created a slew of aids to enable this—including inertial measurement units, Sun sensors, horizon sensors and star trackers.

96. Nuclear Power

In the 1950s, nuclear power seemed to be the answer to everything, even aircraft propulsion. In December 1958, Aviation Week & Space Technology famously and erroneously published claims that the Soviet Union was test-flying a nuclear-powered bomber.

The report turned out to be an elaborate hoax but helped briefly extend funding for U.S. nuclear-powered aircraft research that had begun in 1946. The goal was to develop a strategic missile carrier able to stay on continuous airborne alert for a week or more.

One Convair B-36 was modified with an airborne reactor to measure the effectiveness of shielding, but conversion of another into a nuclear-powered experimental aircraft, the X-6, was canceled in 1961 along with plans for a nuclear-powered bomber. The Soviets, meanwhile, flew a nuclear reactor in a modified Tupolev Tu-95 in the early 1960s, but intercontinental ballistic missiles rendered the concept obsolete.

U.S. research into a nuclear-ramjet-powered missile also ended in the mid-1960s, leaving nuclear power generation for spacecraft as the only continuing application in aerospace. NASA has used radioisotope thermoelectric generators—which convert the heat from radioactive decay into electricity—for many missions, including the planned Mars 2020 rover. Russia has also used small fission-power systems.

With sights set on faster manned flights to Mars, the space agencies of the U.S. and Russia have separately outlined plans to develop high-thrust nuclear propulsion systems based on fission reactors. NASA hopes to fly a small nuclear thermal rocket (NTR) by 2025, and Russia says it could ground-test a prototype nuclear engine as early as 2018. An NTR uses a fission reactor to heat liquid-hydrogen propellant.

97. Reusable Spacecraft

While the dream of a completely reusable orbital launch system has yet to be realized, several developments have achieved key elements of this goal.

Successful reusable winged vehicles such as the space shuttle and Boeing X-37B trace their origins to spaceplane projects of the 1950s and ’60s that attempted to develop an alternate means of atmospheric reentry and landing. The Boeing X-20 Dyna-Soar, for example, was a U.S. Air Force program set up in the late ’50s to develop a reusable capability unlike that of the ballistic reentry capsules in use at the time.

The X-20 was canceled, but a series of Northrop and Martin Marietta-built lifting-body vehicles followed and were tested by NASA in the 1960s and ’70s. Tests validated the concept of an unpowered gliding descent/landing, which contributed to the space shuttle and X-37B as well as to Sierra Nevada Corp.’s Dream Chaser, an optionally piloted spaceplane that was contracted by NASA in 2016 to handle cargo resupply missions to the International Space Station.

Virgin Galactic’s SpaceShipTwo is a hybrid rocket-powered winged vehicle, which is taken to launch altitude by a fixed-wing carrier aircraft; XCOR’s Lynx will takeoff from the runway under rocket power.

The U.S. Strategic Defense Initiative of the 1980s renewed interest in reusable launchers and led to McDonnell Douglas’s 1990s’ DC-X, which proved the viability of the VTOL concept used by both Blue Origin and SpaceX.

98. Jet Packs

“Where’s my jet pack?” is the familiar call of those impatient with the progress of aviation. And in 1961, when Aviation Week first reported on Bell Aerosystems’ rocket belt, the ultimate in personal transportation appeared to be imminent.

The Bell Rocket Belt, or Small Rocket Lift Device as it was called, was developed for the U.S. Army and worked, but its 21 sec. of flight time on 5 gal. of hydrogen-peroxide fuel was too limited to be useful. Today, Mexico’s Technologia Aeroespacial Mexicana builds an improved Rocket Belt (pictured).

Bell went on to develop a flying belt using a small Williams WR19 turbofan for propulsion. This flew in 1968 and led to the Williams Aerial Systems Platform (WASP), which had an uprated WR19-9, could fly for 20-30 min. and reach 60 mph. An improved Williams X-jet flew in 1980 but was abandoned.

However, the idea lives on. New Zealand’s Martin Aircraft is developing the Jetpack, which has two ducted fans powered by a 200-hp V4 engine mounted behind the occupant and a ballistic parachute system for safety. Flight testing is underway, with production planned by year-end.

99. Flying Car

An airplane in every garage has been an aviation dream long before The Jetsons’ flying car premiered on television in 1962. Real flying cars have been featured in Aviation Week since the 1930s. The Waterman Arrowbile was a flying-wing roadable aircraft with detachable wing and propeller; it flew in 1937 but never entered production.

Major aircraft manufacturer Consolidated Vultee produced the ConVairCar, which had a two-seat car with detachable wing, tail and engine mounted on the roof. The prototype flew in 1947. The Fulton Airphibian was a car with detachable fuselage, on which were mounted the wing and tail; it flew in 1950. The Taylor Aerocar with foldable wings was certified in 1956. None of them entered production.

Today, Terrafugia has found out how hard it is to meet both aviation and highway safety requirements as it works to certify its Transition two-seat roadable aircraft, which has wings that fold up at the press of a button. The proof-of-concept Transition first flew in 2006 and certification is still underway. Despite a crash in 2015, Slovakia’s AeroMobil continues development of a flying “roadster” whose wings fold back over the fuselage.

100. Additive Manufacturing

Invented by 3D Systems Corp. in 1984, stereolithography was the first method developed for 3-D printing of plastic and was widely used to make models and prototypes of parts. Selective laser sintering of metal parts was developed for the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (Darpa) in the mid-1980s. In the 1990s, fusion deposition molding of plastic followed from Stratasys and electron-beam melting of metal from Arcam of Sweden. The FAA approved the first additively manufactured part in a General Electric GE90 engine in April 2015 and, in April 2016, CFM began delivering production Leap-1 engines to Airbus with fuel nozzles 3-D printed by Arcam machines.

Supercritical airfoils and winglets reshaped commercial aircraft, in the same way delta wings and relaxed stability became common characteristics of combat aircraft. The tiltrotor introduced a “third way” to fly, but dynamic-system advances have ensured helicopters stay dominant. The “glass cockpit” has evolved with night-vision devices, headup displays, sidesticks and electronic flight bags. But what technologies lie ahead for aerospace? Reusable spacecraft and additive manufacturing for sure, but what about flying cars, jetpacks or another attempt at nuclear-powered aircraft? Only the future will tell.

100 Top Technologies: 'Bonded Structures' to 'Automated Throttles'

100 Top Technologies: 'Protecting the Pilot' to 'Keeping it Together'

100 Top Technologies: 'Aerodynamic Experiments' to 'Modern Monoplanes'

Check 6 Listen as Aviation Week editors discuss—and debate—why they chose the aviation technologies and innovations featured here. AviationWeek.com/podcast

See more content from the 100th anniversary issue of Aviation Week & Space Technology